本紹介26 Africa and its Descendants 1

本紹介26 TAMADA YOSHUYUKI, Africa and its Descendants 1(1995/12/22)の挿画です。挿画に肖像画を描いています。

アフリカ人とアフリカ系米国人の歴史を虐げられた側から捉え直した英文書で、医学生に参考図書として推薦しています。アフリカとアフロ・アメリカの歴史を繋いで日本人が英語で書いたのは初めてだと思います。

一章では、西洋人が豊かなアフリカ人社会を破壊してきた過程を、奴隷貿易による資本の蓄積→欧州の産業革命→植民地争奪戦→世界大戦→新植民地化と辿っています。

二章では南アフリカの植民地化の過程と現状を詳説しています。

三章では奴隷貿易→南北戦争→公民権運動を軸に、アフリカ系アメリカ人の歴史を概観しました。

(再版の表紙絵です。)

(挿画:ジンバブエの田舎の家「インバ」です。)

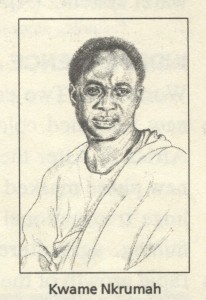

(挿画:ガーナの初代首相クワメ・エンクルマです。)

(挿画:ケニアの作家グギ・ワ・ジオンゴです。)

(挿画:南アフリカの指導者ロバート・マンガリソ・ソブクエです。)

(挿画:南アフリカの指導者スティーヴ・ビコです。)

(挿画:南アフリカの作家アレックス・ラ・グーマです。)

(挿画:南アフリカの作家アレックス・ラ・グーマの夫人ブランシ・ラ・グーマです。)

(挿画:アメリカの指導者マルコム・リトゥルです。)

→「たまだけいこ:本(装画・挿画)一覧」で全体をご覧になれます。

1章の英文です。

“The Colonization of Africa” (Mondo Books, 1995), Chapter 1, pp. 6-27.

PRECOLONIAL AFRICA

Africa has been of great importance to the development of mankind. It has been found that the earliest beings able to make tools once lived in the Rift Valley in East Africa.

A big leap forward was taken when man learnt to sue iron for tools. Another big step was taken when cultivation started on a large scale. Large scale cultivation in Africa began in about 2000-3000 B.C. in both West Africa and Ethiopia.

Between the years A.D. and 1400 Europe developed rapidly. But for all this time European society was in many ways inferior to that of its African neighbours. Cairo was the foremost trade centre in the world and gold was used as the means of payment. Some of this gold was brought from West Africa, and some from Central Africa.

The gold of Africa kept world trading going. World trade was stimulated by the spread of Islam. The gold from Zimbabwe was transported from the interior by Muslim middlemen to the African East Coast.

In West Africa, too, long-distance trade gave birth to new and powerful societies. The West African kingdoms were ruled by kings who appointed local noblemen to collect taxes from the peasants.

Not only in West Africa, but also in Central Africa a centralized organization of society emerged on the basis of surplus production, trade and a growing population.

Parallel to the development of large kingdoms in Africa many groups of people learnt to control nature without kings and kingdoms. Their political systems may be called ‘village rule.’

In Africa, as elsewhere, migrations of cattle-raising people took place when they had to find new pastures, and new places to live for a growing population.

THE FIRST COLONIALISTS

Portuguese adventures were the first Europeans to ‘discover’ Africa south of the Sahara. The first voyages along Africa’s west coast were little more than an extension of the piracy. The Portuguese took away people from the coasts they plundered and brought them home as slaves. As yet slave trade and economic exploitation were on a small scale.

They started to buy gold directly at the coast. In time they also wanted to find a sea route to India. Their aim was to take away from the city-state of Venice their control over the profitable spice trade with the East Indies.

Portugal wanted to start trade by exchanging goods with East Africa. But the project failed as the goods that Portuguese had to offer were inferior to those of the East African tradesmen. The Portuguese seafarers and merchants then decided to achieve for themselves the East African trade monopoly by force. With their superior arms the Portuguese managed to destroy the East African civilization.

In Western history Vasco da Gama, d’Almeida, and Tristan da Cunha have been estimated as ‘great discoverers,’ but they were nothing but destroyers for Africans. A Germany who was present when d’Almeida destroyed Kilwa gives us the following eyewitness report:

“In Kilwa there are many strong houses storeys high. They are built of stone and mortar and plastered with various designs. As soon as the town had been taken without opposition, the Vicar-General and some of the Franciscan fathers came ashore carrying two crosses in procession and singing Te Deum. They went to the place, and there the cross was put down and the Grand-Captain prayed. Then everyone started to plunder the town of all its merchandise and provisions.”

Two days later the city was set on fire.

The main interest of these first colonialists was in spices, cloth, gold, and ivory. They dominated the sea but on land only some narrow strips of the coast. Other countries soon began to compete with the Portuguese for the trade with the East; first the Dutch, then the English and the French gained control over this rich trade.

The European conquest of South America suddenly changed the character and importance of the slave trade. With brutal force the prospering cultures of Peru, Bolivia and Mexico were stamped out by the Spanish conquerors and their silver and gold were stolen. Many Spaniards who set out for this Eldorado found no metals but settled as farmers.

In 1518 a Spanish ship brought the first cargo of Africans directly from Africa to America. This was the start of a trade in slaves which was to continue for three and a half centuries and to bring millions of Africans to America.

The merchants’ profits and the products from America were exchanged in Europe for guns and cloth which were brought to Africa and exchanged for slaves. These humans were sold in America where they produced the goods to be brought to Europe. This was the so-called ‘triangle trade.’ The riches of the capitalists grew while Africa suffered.

European, above all English and American capitalists had gained enormous profits from the trade in slaves and the work performed by the slaves. Slavery was an essential part of the international capitalist market. By this trade the first large-scale collection of wealth was accumulated to speed up the development towards capitalism. The ‘triangular trade’ was one of the foundations of the Industrial Revolution in Europe.

For Africa the consequences of the slave trade were ruinous, not only in the terms of the boundless suffering of the millions who were taken as slaves, and their descendants, but also for those left behind.

An excerpt from Roots

We can find an example of the slave trade from the following scene of the American film Roots which hints to us what the slave trade was like.

In this scene Captain Davies (D) of the slave ship talks with a slave trader John Carrington (C) in his cabin after his ship landed the North America:

C: Did you have a good voyage, Captain?

D: My first officer is dead, ten seamen and the ship’s boy, . . . more than one third of my crew.

C: Oh well, God rest their souls. But the life blood of commerce is goods, sir, goods. How fares your cargo through the passage, Captain?

D: Three thousand elephant teeth have survived the voyage.

C: You’re a pretty wit, sir, a pretty wit . . . elephant teeth indeed . . . .

D: One hundred forty Negroes were loaded aboard the Lord Ligonier at the mouth of the Gambia River.

C: Oh. A loose pack. Well . . . .

D: Of those, ninety-eight were alive when we made port.

C: Ninety eight. Oh, less than a third dead. I have known slavers to make port with less half surviving and still show a handsome profit. My fericitations, Captain.

D: How soon can I unload?

C: Directly we warp your vessel to the wharf.

D: I want you to secure for me flowers of sulphur to burn in the hold. I wish to see my ship clean again.

C: Oh, naturally, sir. After all you’ll be carrying tobacco to London.

D: And in London . . . .

C: Trade goods for the Guinea Coast, and then on to the Gambia River.

D: And more slaves . . . .

C: Indeed, sir. Thus does heaven smile upon us, point to point in a golden triangle. Tobacco, trade goods, slaves, tobacco, trade goods and so on ad infinitum. All profit, sir and none the loser for it.

D: Tell me, Mr. Carrington, do you ever wonder . . . .

C: On what topic, sir, to what end?

D: As to whether or not we are just as much imprisoned as are those chained in the hold below?

C: I do not follow your meaning, sir.

D: It sometimes feels that we do harm to ourselves by taking part in this endeavor.

C: Harm? What harm can there be in prosperity, sir? What harm is a full purse, I’d like to know.

D: No, no, I doubt that you’d like to know, Mr. Carrington. I doubt that either of us would truly like to know.

C: Would you be interested in coming to the auction, Captain? I warrant you’ve never seen anything like it.

D: No, I am sure I have not, Mr. Carrington. I do know that I am not interested in seeing it now . . . or ever.

MONOPOLY CAPITALISM AND IMPERIALISM

The European capitalists used the profits from the slave trade and from slave labour in the mines and plantations in America to develop their own industries. Gradually the industrial capitalists grew more powerful than those capitalists who invested in trade.

While the slave traders and the plantation owners wanted to keep slavery, the industrial capitalists’ main interest was to buy workers on a ‘free labour market.’ They could abolish slavery. The capitalism of free competition was turning into monopoly capitalism.

A tremendous development of the productive forces was made with the result that the industries produced more goods than could be consumed, they produced more goods than people could afford to buy. Consequently, the industrialists had to look for new markets.

Capital export, i.e. investment abroad, become particularly important to monopoly capital. The capitalists were also looking for raw materials for industrial production, and new markets for their products.

THE COLONIAL DIVISION OF AFRICA

The European states set out to conquer the rest of the world as colonies. These colonies became the protected hunting ground for each mother country’s own capitalist class. At the beginning of the 20th century, except for only Ethiopia and Liberia, the whole of Africa was divided between the imperialist powers.

The ruling classes in Europe hoped that the acquisition of colonies would calm the social unrest in their own countries. The competition for colonies became so fierce that war was threatened between the imperialist powers. But a common interest in exploiting the colonized peoples and the fear of a rising working class in their own countries won over the contradictions of the imperialists. To solve the problem of competition they sat down to negotiate. A war was postponed until 1914, and then it led to a redistribution of the colonies.

At the so-called Berlin Conference in 1884-85 Africa was formally divided between the colonial powers: England, France, Germany, Belgium, Italy, Portugal, and Spain.

COLONIALISM

After the Berlin Conference the process of actual occupation and military domination had to be carried out. In a few cases there was only weak African resistance to colonial occupation, mainly because in some areas it was the custom for Africans to welcome all strangers. It was only later that they understood that the colonialists had anything but peaceful purposes. In most cases colonization met fierce resistance and led to terrible persecutions, and sometimes to outright genocide.

In order to obtain labour for plantations and mines set up and owned by the colonizers and obtain cash for the colonial administration, the colonial powers introduced forced labour, compulsory cultivation of export crops and various forms of taxation. In order to be able to pay taxes, and also gradually to be able to buy the European manufactured goods which began to flood Africa, the adult men from the villages worked for the colonialists part of the year. The migrant workers who were forced into a capitalist monetary economy on short-term contracts were not given the chance to learn new skills. They were used as unskilled manual labour on the plantations and the mines, and when their contract ended they could be replaced by others. The wages they received were not enough to support the whole family which had to remain in the village to earn their own living.

In many colonies the inhabitants were forced to grow crops for export instead of, as before, for their own living. In other areas, land was taken over for plantations and run by European settlers who hired the now landless peasants as their agricultural workers, often only for a short season. Agricultural production concentrated on growing one single crop is called monoculture. When the prices paid by these capitalist countries for agricultural products fell, so did the income that African countries could get for their export.

Kwame Nkrumah, the first prime minister of Ghana, wrote in his autobiography about the British colonial administration of this time:

“In all the years that the British colonial office administrated this country, hardly any serious rural water development was carried out. What this meant is not easy to convey to readers who take for granted that they have only to turn on a tap to get an immediate supply of good drinking water. This, if it had occurred to our rural communities, would have been their idea of heaven. They would have been grateful for a single village well or standpipe.

As it was, after a hard day’s work in the hot and humid fields, men and women would return to their village and then have to tramp for as long as two hours with a pail or pot in which, at the end of their outward journey, they would be lucky to collect some brackish germ-filled water from what may perhaps have been little more than a swamp. Then there was the long journey back. Four hours a day for an inadequate supply of water for washing and drinking, water for the most part disease-ridden!

This picture was true for almost the whole country and can be explained by the fact that water development is costly and no more than a public service for the people being administered. It gave no immediate prospect of economic return. Yet a fraction of the profits taken out of the country by the business and mining interests would have covered the cost of a first-class water system.” (Africa Must Unite)

INDEPENDENCE AND NEO-COLONIALISM

World War Two ended with energy directed towards building a new reformed colonialism, or neo-colonialism. (See Appendix Africa 2) After the war, the world capitalist economy entered a new phase marked by the dominance of the USA and the rise of huge transnational corporations. Capital investment in African mining, agriculture, and industries increased, which led to the rapid growth of the African working class.

Landlessness and poverty led to the growth of large urban slums. Resistance began to take new forms as peasants and workers became organized. The middle-class nationalist movements changed their tactics to calls for national independence. In 1957 Ghana became independent as did many nations around 1960.

The post-war world created a new world order in which imperialism no longer had a part to play. The power of American capital and the new transnational corporations called for the abandoning of the restrictions on trade and investment. It was the age of the United Nations. The European colonial powers began to question the increasing cost of maintaining their empires.

In the peasant-based colonies, and in other colonies where the settlers were weak, there took place a relatively easy transfer of power into the hands of the African elite. However, in other colonies where the settlers were able to hold onto political power (Algeria, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and so on), independence was only won after long and bitter armed struggles. In most cases, the new independent governments inherited economic dependence. The dependence could be used by the imperialist forces to further their aims. It rests on a continued colonial division of labour and foreign control of key sectors of the economy. Colonialism destroyed the old society. Yet colonial regimes and their African allies did not push through the full capitalist transformation they had begun. Instead, they continued to get profits from the traditional economy and patch it up where it threatened to break down. Sooner or later, the system had to collapse.

Now Africa has so many problems, such as poverty, hunger, drought, racial conflicts, diseases and so forth. The 1994 15 massacre in Rwanda left us with a sense of desperation. In that racial conflict more than 500,000 people were slaughtered and more than 2 million were forced to flood into their neighbouring countries. The 1995 Ebola outbreak in Zaire spread fear around the globe. Furthermore, the AIDS situation is now devastating. The disease accounts for 300,000 deaths per year in sub-Saharan Africa, a rate that is expected to reach 900,000 in five years, according to the World Health Organization. Health officials reckon that AIDS began travelling 20 years ago down the transport routes from Central African countries. The next target is South Africa where the peaceful transformation of power was made through the 1994 multi-racial election.

The colonial heritage is far too heavy for African countries to bear in all ways.

APPENDIX AFRICA 1

Nkrumah wrote the British malicious intention toward neo-colonial system he had met at the time of the independence:

“As a heritage, it was stark and daunting, and seemed to be summed up in the symbolic bareness which met me and my colleagues when we officially moved into Christianborg Castle, formally the official residence of the British Governor. Making our tour through room after room, we were struck by the general emptiness. Except for an occasional piece of furniture, there was absolutely nothing to indicate that only a few days before people had lived and worked there. Not a rag, not a book was to be found; not a single reminder that for very many years the colonial administration had had its centre there.

That complete denudation seemed like a line drawn across our continuity. It was as though there had been a definite intention to cut off all links between the past and present which could help us in finding our bearings. It was a covert reminder that, having ourselves rejected that past, it was for us to make our future alone. In a way it hinged with some of our experience since we had taken office in 1951. From time to time we had found gaps in the records, connecting links missing here and there which made it difficult for us to get a full picture of certain important matters. There were times when we had an inkling of material withheld, of files that had strayed, of reports that had got ‘mislaid.’ We were to find other gaps and interruptions as we delved deeper into business of making a going concern of the run-down estate we had inherited. That, we understood, was part of the business of dislodging an incumbent who had not been too willing to leave and was expressing a sense of injury in acts of petulance. On the other hand, there may have been things to hide. It was part of the price, like much else, that we had to pay for freedom. It is a price that we are still paying and must continue to pay for some time to come.” (Africa Must Unite)

APPENDIX AFRICA 2

A Kenyan writer Ngugi Wa Thiong’o pointed out a neo-colonial situation in Kenya in an interview by a South African weekly newspaper:

“Ngugi’s critique of Kenya is that it is politically formally independent, but its economy is still controlled from the outside: ‘All the financial institutions, industrial institutions, commerce and trade are an extension of the western colonial powers.

‘Instead of British colonial interests being the dominant ones, wider interests have come in―West German, American, Japanese and French.’

Ngugi has particularly harsh words for those Western journalists who use Nairobi as a jumping-off point to cover the rest of Africa but seem to say little about the authoritarianism and civil rights abuses in Kenya itself.

Many people were left with the impression that Kenya was a success story but ‘this label is always used for those countries in Africa that are ideologically closest to the West. It simply means there has been no break with the colonial past.

‘It means the creation of a small group of Kenyans with very close relations with Western interests and a very large majority of poor―10 millionaires and 10 million poor.

‘Neo-colonialism has to be overcome in the same way that colonialism was overcome. It is not possible for the next leap forward for Africa until that has been done. The whole basis has to be Africa-based, where the wealth of Africa stays in Africa. ‘” (Supplement to the Weekly Mail, June 30 to July 6, 1989)