<連絡事項再確認>

5月15日(水)も1コマ目は通常授業、4コマ目は用語2章の残りと3、4章。

試験が必要な人は単独でも複数でも協力するよ。メールで時間と場所を決めて、やろ。

<今回は>

1コマ目が4回目、4コマ目が5回目の授業でした。

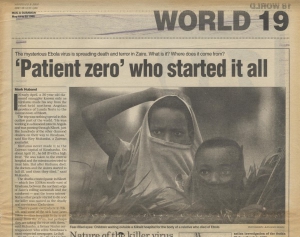

1コマ目はBSEのたんぱく質が病原体になりうる話が1960年代のネーチャーに出たとか、いろいろ。早く自分のやりたいことをみつけて、自分のために自分の意思で勉強しぃや、みたいな話です。

The struggle for AfricaのTHE CONFLICT BETWEEN THE BRITISH AND THE BOERSとThe UNION OF SOUTH AFRICA ANS RESERVESを川島さんが、THE APARTHEID REGIMEとTHE POLICIES OF APARTHEIDを佐原くんがやってくれました。

それしか出来なかったねえ。

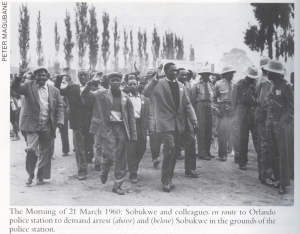

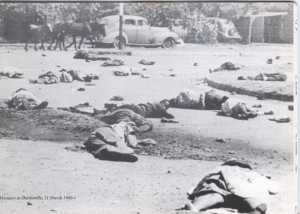

次回はMass MOBILIZATION AND OPPRESSIONとTHE ARMED STRUGGLE(方波見さん)やって映像も見てもらわんとね。

南アフリカの歴史背景の大きな山の一つ①ヨーロッパ移住者がアフリカ人から土地を奪って課税して安価なアフリカ人労働者の一大搾取機構を打ち立てた、②アパルトヘイト政権とアフリカ人の抵抗運動、とだけ終わりました。

<次回は>Mass MOBILIZATION AND OPPRESSIONとTHE ARMED STRUGGLE

その辺りを貼っときます。

*1652年にオランダ人が到来

*1795年にイギリス人がケープを占領

*1806年にイギリス人が植民地政府を樹立

*1833年にイギリス人がケープで奴隷を解放

*1835年にボーア人が内陸部に大移動を開始(グレート・トレック)

*1854年頃には海岸線のケープ州とナタール州をイギリス人、内陸部のオレンジ自由州とトランスバール州をオランダ人、で棲み分ける

*南アフリカは戦略上そう重要ではなかった

*金とダイヤモンドの発見で状況が一変、一躍重要に

*1867年キンバリーでダイアモンドを発見

*1886年1ヴィトヴァータースランド(現在のヨハネスブルグ近郊)で金を発見

*1899年金とダイヤモンドの採掘権をめぐって第二次アングロ=ボーア戦争(~1902)

*イギリスの勝利。

*1910年南アフリカ連邦成立(イギリス人統一党とアフリカーナー国民党の連合政権、統一党が与党、国民党が野党)

*1912南アフリカ原住民民族会議結成。

*1913原住民土地法。

*1925南アフリカ原住民民族会議→アフリカ民民族会議(現与党)に改称。

*1948アパルトヘイト政権成立。

4コマ目は1、2章(途中まで)の解説と発音練習、専門分野の名称は尾関さんがやってくれました。

まだ読んでない人は各章の紹介→例文→解説→練習問題をやってからPronunciation of Termsを繰り返し覚えや。

1、2章の圧縮フォールダー(zip)はすでに置いてあるけど、あらたに3・4章を置いときます。ダウンロードできない人はメールしてくれたら他の方法を考えられると思います。

来週、また。

今日の分の日本語訳、貼っときます。細かいところは見比べてや。

THE COLONIZATION OF SOUTH AFRICA 南アフリカの植民地化

When Europeans arrived in the southern part of Africa, different peoples had been living there for some centuries. Groups of San people lived in the mountains and on the edges of the deserts in the southeast. They hunted rock rabbits, lizards, locusts and so forth. Near them lived the Khoikhoi who herded cattle and had more permanent camps than the San. They sometimes intermarried.

南部アフリカにヨーロッパ人が到着した時、そこにはすでに何世紀にも渡って様々な民族が住んでいました。サンの人々はいくつも集落を造って南東部の山や砂漠の端に住んでいました。その人たちは岩兎や蜥蜴や蝗などの狩りをして暮らしていました。サン人の近くには、家畜を飼うコイコイ人が住んでいて、狩りをして移動するサン人よりは定住型の生活を営んでいました。時にはサン人とコイコイ人は結婚することもありました。

The Europeans began to settle down in the latter half of the 17th Century on the initiative of the Dutch East India Company. The Dutch traders had out-rivalled the Portuguese and taken over the spice trade with Asia. Because the voyage to Asia was long, the Company built a depot of provisions at the Cape of Good Hope in 1652. A small white settlement was to grow vegetables and supply other services for the Company. The colony was completely dependent on the Company, among other things for the supply of arms. The Dutch colonialists called themselves Boers. It means farmers in Afrikaans, their Dutch dialect.

オランダ東インド会社に率いられて、17世紀の後半にヨーロッパ人は定住を始めました。オランダの貿易商はポルトガル人との競争に勝ち、アジアの香辛料貿易を引き継ぎました。アジアへの航海は長いものでしたので、会社は1652年に喜望峰に食料を補給するための基地を築きました。その小さな白人入植者の居留地は野菜を育て、会社のために色々なものを提供しました。居留地はすべてを会社に依存していましたが、なかでも武器の供与は全て基地任せでした。オランダの植民地主義者たちは自らをボーアと呼びました。それはオランダ語由来の言葉であるアフリカーンス語で、農民という意味です。

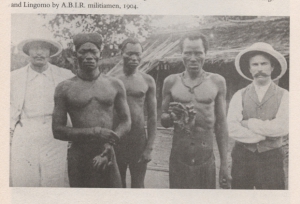

Disputes between the Boers and the Company made them move further inland. The first people they met were the Khoikhoi, whose pasture they conquered. Worse still for the Khoikhoi, the settlers forced them to hand over their cattle. It so was the very basis of their social system. The Khoikhoi were forced to work for the European settlers. The whites’ intrusion meant catastrophe for the San. Only a few San escaped and fled into the Kalahari desert. Their descendants live to this day under much more primitive conditions than did their forefathers in their rich soil.

会社との間で諍いを起こしてボーア人は、内陸の方に移動しました。ボーア人が最初に遭遇した人たちはコイコイ人で、その人たちの放牧地をボーア人が征服しました。コイコイ人にとって更に悪いことには、入植者達は牛を引き渡すように強要しました。それはコイコイ人の社会システムの基盤そのものでした。コイコイ人はヨーロッパ人入植者に、労働を強制されました。白人の侵入者は、サン人には悲劇的な結末を意味しました。ごく僅かのサン人は逃亡)、カラハリ砂漠に逃げこみました。その人たちの子孫は、今日でも、肥沃な土地に住んでいた祖先たちよりも原始的な状態で暮らしています。

The Xhosa and the Zulu peoples were most numerous in South Africa. Land was owned collectively, but cultivated individually. This might be called a moderate kind of socialism. When these highly developed cultures with their strong military organization clashed with the Boers, they could not be defeated as easily as the Khoikhoi and the San. The Wars of Dispossession started in 1871. The battles were many and fierce during the nine wars. The whites could only consolidate their control over what was formerly African land by crushing these African military kingdoms with superior arms. This process was almost completed in 1881. But the Boers never conquered South Africa completely. Conquest was completed only when the British forces took over the process.

南アフリカでもっとも人口の多かったのは、コサ人とズール人でした。土地は個人ではなく全体で共同所有されていましたが、個人個人が耕やしていました。一種の穏やかな社会主義と呼び得るものかも知れません。強大な軍を持つ高度に発達した文化がボーア人とぶつかった時、コイコイ人やサン人が簡単にやられたように、コサやズールーの人々がやられることはありませんでした。1871年に、略奪戦争が始まりました。9つの略奪戦争では、戦闘も数多く、激しいものでした。白人たちは優れた武器を使って、軍を持つアフリカの王国を破壊することによって、元はアフリカ人所有の土地に対する支配権を確立したのです。この過程は1881年には、ほぼ完成していました。しかし、ボーア人は完璧に南アフリカを征服しわけではありません。イギリス軍がその過程を引き継いで初めて、征服が完了したのです。

Britain feared that French control of the Cape could jeopardize British interests in India and trade with the East, and in 1795 sent a large British force to the Cape and forced the Dutch governor to capitulate. The Boers at once came into conflict with Britain. Britain was looking for raw materials and new markets for industrial goods. Slave trade and slave labour were no longer necessary. But for the Boers slavery was the foundation of their economy, so they resisted all attempts to abolish it. This contradiction resulted in bitter conflicts between them and the British colonialists. In 1833 the British managed to abolish slavery in the Cape. Many Boers, particularly the wealthy ones, left the Cape and moved inland in big ox caravans. This was called the Great Boer Trek. The Boers who stayed in the Cape needed workers for their farms, so they imported workers from Indonesia and Malaysia, Dutch colonies in Asia.

イギリスはインドおよび東洋との貿易で、ケープをフランスが支配することになればイギリスの利益が危険にさらされるかもしれないのではないかと心配しました。そして、1795年にはケープへ大規模なイギリスの軍隊を送り、オランダの植民地相に降伏することを強制しました。ボーア人は、直ちにイギリスと衝突しました。イギリスは、原料および工業製品の新しい市場を探していました。奴隷貿易と奴隷の労働は、もはや必要ありませんでした。しかしボーア人には奴隷制度が経済の基礎でしたから、ボーア人は奴隷制度を廃止する試みすべてに反抗しました。この矛盾は、ボーア人とイギリスの入植者の苦しい対立を生む結果に終わりました。1833年には、イギリス人がどうにかケープの奴隷制度を廃止しました。多くのボーア人、特に豊富なものがケープを去り、大きな雄牛の隊列を組んで内陸に移動しました。これはボーア人の大移動と呼ばれました。ケープにとどまったボーア人は、自分たちの農場のための労働者を必要としましたので、アジアのオランダ植民地インドネシアとマレーシアから労働者を輸入しました。

By 1854 South Africa was divided into four provinces. The British claimed the Cape and Natal, the coastal provinces rich in soil. The Boers had established two inland republics: the Orange Free State and Transvaal, which Britain had to recognize as autonomous.

1854年までに、南アフリカは4つの州に分割されました。イギリス人はケープおよびナタールの土壌の豊かな沿岸地方を要求しました。ボーア人は内陸の2つの共和国オレンジ自由国とトランスヴァールを設立し、イギリスはその2州を自治領として認めざるを得ませんでした。

The number of colonizers of British origin gradually grew. In Natal province sugar cultivation was started on a large scale at the end of the 19th century, and Indians were imported as indentured labour (See Appendix South Africa 1).

イギリスから来た入植者の数は徐々に増えていきました。ナタール州では、19世紀の後半に大規模な砂糖栽培が始められ、インド人が契約労働者として輸入されました。(附録<南アフリカの1>を参照)

The British and British capital became really interested in South Africa only when diamonds were found in 1867 and gold in 1886. This also caused a growing conflict with the Boers, since the rich deposits were found in their republics.

イギリス人とイギリス資本は、1867年にダイヤモンド、1886年に金が見つかったに初めて、南アフリカに本当に興味を持つようになりました。豊富な鉱物がボーア人の共和国で見つかったので、そのことでさらにボーア人との衝突が激しくなりました。

THE GROWTH OF MINING CAPITAL 鉱山資本の成長

The first diamonds were discovered in the area which later was to become the Kimberley diamond fields.

まず初めのダイヤモンドは、その後キンバリー・ダイヤモンドの産地になる地域で発見されました。

The diamonds on the surface were soon depleted. A more costly technique was then required to exploit diamonds under the surface. This furthered capital concentration, i.e. the concentration of ownership in fewer hands. In 1888 all diamond mines were controlled by a company called de Beers Consolidated, which before the turn of the century controlled 90% of world production. The company was in the hands of the British imperialist Cecil Rhodes, who also was Prime Minister in the Cape colony.

地表のダイヤモンドはすぐに堀り尽されました。その後、よりお金のかかる技術が地下のダイヤモンドを開発するために必要とされました。これは更に資本の集中を促しました、つまりより少数の手の中に所有権が集中したわけです。1888年には、ダイヤ鉱山が全てデ・ビアスと呼ばれる会社によって支配され、20世紀になる前には世界生産の90%をその会社が支配していました。その会社は、イギリスの帝国主義者であり、ケープ植民地の首相でもあったセシル・ローズの手中にありました。

THE CONFLICT BETWEEN THE BRITISH AND THE BOERS 英国人とボーア人の対立

The Boers had every reason to be suspicious of British capital. They viewed the railway with apprehension; it wound northwards from the Cape, and charged heavy freight fees and duties in the harbour. The Boers wanted to keep the gold-rich areas for themselves, and they looked for allies. The rivalry between the European imperialist powers in `the scramble for Africa’ gave the Boers a new chance to get rid of their dependence on the British harbours. With German and Dutch capital a railway line was built from Transvaal to the Mozambican coast.

ボーア人がイギリス資本を信用しないのには充分な理由がありました。ボーア人は、不安な思いで鉄道を見ていました。それはケープから北の方へ延び、通行料金と港での税金を課しました。ボーア人は自分のために金の埋蔵量が豊かな地域を維持したかったので、同盟国を探しました。アフリカ争奪戦でのヨーロッパの帝国主義列強間の競争は、ボーア人にイギリスの港の依存を取り除く新しい機会を与えました。ドイツとオランダの資本で鉄道がトランスヴァールからモザンピークの海岸間に建設されました。

The ruling Boers in Transvaal tried to channel income from the British-owned mines there to themselves. The tense situation between the Boers and the British led to the second Anglo-Boer War in 1899. It ended in 1902 with victory for British imperialism. Cruelties were committed on both sides, but the concentration camps set up by the British for Boer women and children left especially bitter scars.

トランスヴァールを支配するボーア人は自分たちの方に、イギリスに所有された鉱山からの収入を向けようと努力しました。ボーア人とイギリス人との間の緊張した状況は1899年の第二次アングローボーア戦争を生みました。1902年にイギリスの帝国主義者の勝利で戦争は終了しました。双方で残虐行為が行われましたが、イギリス人がボーア人女性と子供用に建設した強制収容所は、ボーア人に特に酷い傷跡を残しました。

The Boers traditionally had two enemies: the indigenous Africans, whose cattle and land they coveted and whom they tried to make into slaves, and British imperialism, which was out to exploit the riches of South Africa. But when it came to exploiting the Africans, the Boers made common cause with the economically superior British.

昔からボーア人には二つの敵がありました、欲しがっていた家畜を奪い、奴隷に仕立て上げたその土地に住んでいたアフリカ人と、躍起になって南アフリカの冨を搾り取ろうとするイギリス帝国主義でした。しかし、アフリカ人を搾取するという点では、ボーア人は経済的に優位だったイギリス人と共通の大義がありました。

THE UNION OF SOUTH AFRICA AND RESERVES 南アフリカ連邦とリザーブ

During the Boer War the British government had claimed that its objective was to protect the Africans. But in the peace treaty the whole question of the political future of the Africans in South Africa was left in the hands of the Boers and the British colonialists. In May 1910 the Union of South Africa was created, which meant that the British government handed over all political power to the whites in South Africa. It was only the negotiated product of the Boers and the British colonialists with their common cause of exploiting the Africans.

ボーア戦争の間じゅう、英国政府は戦いの目的はアフリカ人を保護することだと言っていました。しかし、平和協定を結ぶときには、南アフリカのアフリカ人のこれからの政治に関してはすべての問題をボーアじんとイギリス人植民地主義者の手に収めたままにしてしまったのです。1910年の5月に南アフリカ連合を創設しましたが、それは英国政府が政治的な権利をすべて南アフリカの白人に引き継いだということだったのです。アフリカ人を搾取するという共通の目的のためにボーア人とイギリス人植民地主義者が作り出した妥協の産物に過ぎなかったのです。

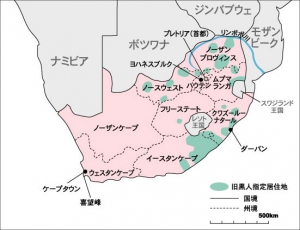

The first Union parliament created the African reserves through the Native Land Act in 1913, which made previous practices the law. Whites were forbidden to buy or rent land in the reserves, and Africans could neither buy nor rent outside the reserves. The only exception was the Cape province where, for some time, Africans were still allowed to purchase land. The law meant that 78% of the population was supposed to live in reserves comprising only 7.3% of the area of the country.

最初の連邦議会は1013年の原住民土地法でアフリカ人リザーブを創設しました。それは今までの慣習を法制化したものでした。白人にはリザーブ内の土地を買うこと、借りることが禁止されました。アフリカ人はリザーブ外では土地を買うことも借りることも出来ませんでした。唯一の例外はケープ州で、暫くの間はアフリカ人が土地を購入することが許されました。法律が意味するところは、人口の78パーセントが国土の僅か7.3%からなるリザーブに住むことになるということでした。

For a farming people to be deprived of their land was a hard and bitter blow, which at once strengthened opposition. The South African Native National Congress, which changed its name to the African National Congress (ANC) in 1925, was formed in 1912 to unite the Africans in defence of their right to land and to demand political rights. When the Land Act was still in preparation, a delegation of leading Africans was sent to London. Their mission was fruitless and the African leaders were beginning to realize that no solution to their plight could be found in London.

農民が土地を奪われれば大打撃で、すぐに反対運動が起きました。1912年、土地の権利を守り、政治的な権利を求めるために、そののち1925年にアフリカ民族会議(ANC)と改名する南アフリカ原住民民族会議が創設されて、アフリカの結束をはかりました。土地法がまだ準備段階のうちに、アフリカ人指導者の代表がロンドンに派遣されました。派遣の成果もなく、アフリカ人指導者はロンドンにでは自分たちの窮状の解決策は見出せないと悟り始めていました。

The 1913 Native Land Act was in force until 1936. That year a new law, the Native Trust and Land Act, extended the area of the reserves to 13.7%. This law was in force till all the apartheid laws were abolished in 1991. This law was the foundation of the apartheid regime’s land consolidation for the `homelands,’ the so-called Bantustans.

1913年の原住民土地法は1936年まで効力がありました。その年に新法原住民信託土地法が制定されて、リザーブの範囲が13.7パーセントにまで拡大されました。この法律はすべてのアパルトヘイト法が廃止される1991年まで有効で、アパルトヘイト政権が力を入れたホームランド、いわゆるバンツースタン政策の根幹でした。

AFRICAN RESISTANCE アフリカ人の抵抗

The Africans in South Africa have a long and bitter experience of anti-colonial struggle. In the early days, the method of protest was to send futile petitions to the British government. At this time the nationalist movement still consisted of persons speaking for the mass of the Africans rather than with them. In the beginning there were few workers in the movement. These were absorbed in the Industrial and Commercial Workers’ Union (ICU) which was formed in 1919, during the post-war rise in workers’ consciousness.

The South African Communist Party (SACP) was formed in 1921. Many Communists worked inside the ICU, which first only raised wage demands, but in the late 1920’s developed into a general protest movement against racial discrimination.

南アフリカのアフリカ人は植民地化に抵抗して来た長くて厳しい歴史があります。初期の頃は、抵抗と言っても英国政府に代表を送って懇願するだけでした。その頃は国民的な動きと言っても誰かが人々に語りかけるのが関の山で大衆とともに闘うということはありませんでした。当初、抵抗運動にはほとんど労働者は関わっていませんでした。その僅かな労働者は第一次大戦後の労働者の意識が高まっていた時期の1919年に創設された工業・産業労働者組合(ICU)に吸収されました。南アフリカ共産党が1921年に創られました。たくさんの共産党員がICU内で活動して最初の賃金引き上げの要求を提案し、その運動が1920年代後半には人種差別反対の全般的な抗議運動に発展して行きました。

The struggle pursued by the ANC, the ICU and the Communist Party against the pass laws, for land to the Africans, for political rights, better working conditions and against discrimination, was waged with all available non-violent methods. Meetings and rallies were held, demonstrations organized, signatures collected for open letters, and support given to strikers. But the government would not be influenced and instead replied by ruthlessly crushing opposition.

ANCとICUと共産党はパス法や人種差別に反対し、アフリカ人の土地や政治的な権利や労働条件の改善を求めて可能な手段で闘いましたが、闘いはすべて非暴力で行なわれました。会合や集会が開かれ、デモが組織され、公開質問状のための署名も集められ、ストライキに参加した人たちへのカンパも寄せられました。しかし、政府は抵抗運動には影響されることなく、容赦なく反対勢力を押しつぶすことで対抗しました。

The Second World War meant in South Africa as in all colonized parts of Africa, a new self-awareness among the Africans. In 1945 the ANC adopted its new programme – Africans’ Claims – which laid the basis for later stands. The ANC demanded general and equal suffrage, a redistribution of land, total freedom of movement and habitation and an end to all discrimination.

第二次世界大戦は、植民地化された他のすべてのアフリカ地域と同じように、南アフリカでもアフリカ人の中に新しい自覚を生み出しました。1945年にANCは新しい計画「アフリカ人の主張」を採用し、それが後の闘いの路線の基礎になりました。ANCは平等な普通選挙権と土地の再分配、行動と居住の全面的な自由と、すべての人種差別の撤廃を要求しました。

The methods of struggle were still boycotts, demonstrations, and other forms of organized, passive resistance. But an impatience with the futile attempts to appeal to 'enlightened’ white leaders led to a greater degree of militancy, and to the formulation of 'African nationalism’ as the ideological platform. Responsible for the radicalization above all was the Congress Youth League, the youth section of the ANC, which was formed in 1944.

闘争のやり方は、ボイコットやデモ、組織的ではあっても積極行動を伴わない抵抗の形を取り続けました。試みが失敗しても我慢強く「啓けた」白人指導者に訴え続けたために、やがてはかなりの程度にまでアフリカ人の活動が鋭くなり、考え方の拠り所として「アフリカ人ナショナリズム」を生み出す結果となりました。中でも闘争の先鋭化に大きく関わったのは、1944に創設されたANCの青年部門、国民青年同盟でした。

The first big confrontation after the War was the miners’ strike in 1946. It was led by the African Mine Workers’ Union which was formed in 1941 and had grown rapidly. A hundred thousand miners struck for a week. The strike was brutally suppressed by police in actions where hundreds were killed and injured. The miners’ strike pointed to the foundation of resistance: the mines are the vital nerve of the South African economy and the core of the nationalist movement was more and more made up of the working class, with a higher consciousness than in most African states.

大戦後の最初の大きな対決は1946年の鉱山労働者のストライキでした。率いたのは1941年に結成されて以来急速に成長したアフリカ人鉱山労働者組合です。十万人の鉱山労働者が一週間のストライキを行ないました。警察が出動してストライキを容赦なく抑え込み、数百人の死傷者を出しました。この鉱山労働者のストライキは解放闘争の基礎を暗示しました。つまり、鉱山は南アフリカ経済の中枢神経で、国民運動の核が、他のアフリカ諸国よりも意識の高い労働者階級によって形成されていくことになったのです。

Appendix South Africa 1 附録

南アフリカ1

Mahatma Gandhi experienced discrimination when he visited Pretoria in the late 1890s. He stood up against the discriminatory laws and made a speech for co-operation to the Indian audience:

マハトマ・ガンジーは1890年代後半にプレトリアを訪れた際に、人種差別を体験しています。ガンジーは差別法に反対して立ち上がり、集まったインド人に協力を求めて次のように演説しました。

GANDHI: I want to welcome you all, everyone of you. We have no secrets. Let us begin by being clear about General Smuts’ new law. All Indians must now be fingerprinted like criminals, men and women. No marriage, other than a Christian marriage, is considered valid. Under this Act our wives and mothers are whores and every man here is a bastard.

KHAN: He has become quite good at this.

ガンジー:お集まりのみなさん、ようこそお出で下さいました。私たちの間では秘密はありません。先ずは、スマッツ長官の新法についてはっきりさせることから始めましょう。現在の法律では、インド人は男女を問わず、誰もが囚人のように指紋を押さなければいけません。キリスト教式の結婚以外は、どんな結婚も法的に正当だとは見なされません。現法律の下では、妻も母親はすべて売春婦で、ここにいる男はみな正式には父親のいないろくでなしということになります。

カーン:この演説、なかなかうまくなったねえ。

GANDHI: And a police man, passing an Indian dwelling, Ah, I would not call them homes, may enter and demand the card of any Indian woman whose dwelling it is. Understand he does not have to stand at the door, he may enter.

AUDIENCE: I will not allow . . .

AUDIENCE: I swear to Allah. I’ll kill the man who offers that insult to my home and my wife. And let them hang me.

AUDIENCE: I say talk means nothing. Kill a few officers before they disgrace one Indian woman, then they might think twice about such laws. In that cause I would be willing to die.

ガンジー:そして、警察官はインド人の住まい、ええ、私はインド人の住まいを家とは言いたくないので敢えて住まいとは呼ばないんですが、そのインド人女性の住まいに入って来て、カードを見せろと言えるんです。

参加者の一人:俺は許さん……。

別の参加者:アラーの神に誓って言う。俺の家と妻に向かってそんな侮辱を加える奴は殺してやる。この手で吊してやる。

また別の参加者:口で言っても意味がない。インド人の女を辱める前に警官を殺そう、そうすりゃ奴ら、その法律を考え直すさ。そのためなら、俺はこの命をかけてもいい……。

GANDHI: I praise such courage. I need such courage because in this cause I, too, am prepared to die, but my friends, there is no cause for which I am prepared to kill. Whatever they do to us, we will attack no one, kill no one, but we will not give our fingerprints, not one of us. They will imprison us, and they will fine us. They will seize our possessions, but they cannot take away our self-respect if we do not give it to them.

AUDIENCE: Have you been to prison? They beat us and torture us. I say that . . .

ガンジー:その勇気は立派です。その勇気は必要です。私もこの大義のために命をかけていますから。しかし、みなさん、殺してもいいという大義など存在しません。あの人たちが何をしようと、私たちは誰も襲ってはいけません。誰も殺してはいけません。誰も指紋を押してはいけません。この中の、誰一人だって。あの人たちは私たちを投獄し、罰金刑を科すでしょう。財産を没収するでしょうが、私たちさえ指紋を押さなければ、あの人たちが私たちから自尊心を奪い去ることは出来ません。

参加者の一人:あんた、刑務所に入ったことがあるのか?奴らは殴るし、拷問するぞ。俺が言いたいのは……。

GANDHI: I am asking you to fight, to fight against their anger, not to provoke it. We will not strike a blow, but we will receive them. And through our pain we will make them see their injustice and it will hurt as all fighting hurts but we cannot lose, we cannot. They may torture my body, break my bones, even kill me. Then they will have my dead body, not my obedience. We are Hindu and Muslim, children of God, each one of us. Let us take a solemn oath in his name that come what may we will not submit to this law.

All: God save our gracious King, Long live . . . (From the American film Gandhi)

ガンジー:私はあなた方にあの人たちの怒り挑発せずに、その怒りと闘って下さいとお願いしているのです。殴るんではなく、殴られて下さい。私たちの痛みを通して、あの人たちに自分たちの不正に気づかせるのです。すべて喧嘩は傷つくもので、怪我もするでしょう。あの人たちは私の体を責め、骨を砕き、私を殺すかも知れません。殺せば、私の死体を手にするかも知れないが、私を服従させられはしません。私たちはヒンズー教徒でもイスラム教徒でも、すべて神の子どもです。何が起ころうとも、この法律には決して従わないと神の名の下に誓いましょう。

全員(国家斉唱):神よ、我らが慈悲深き女王を守りたまえ。我らの気高き女王よ、長命であれ……。(米国映画『ガンジー』より)

THE 1948 APARTHEID REGIME 1948年のアパルトヘイト政権

African resistance put a strain on the white alliance of the Afrikaners and the British, and created a crisis in the South African system. Social changes lay behind the increased African militancy, and the ruling party, close to mining capital, was unable to handle the situation.

アフリカ人が抵抗したので、アフリカーナーと英国人による連合政権は緊迫し、南アフリカの制度は危機的な状況に陥りました。アフリカ人がますます激しく抵抗する背景には様々な社会変化があり、鉱山資本に近い与党は、その状況にうまく対処出来なくなりました。

The manufacturing sector in South Africa grew rapidly during the War when the hold of imperialism loosened, and Britain and the United States needed consumer goods from abroad because their own production was focused on manufacturing armaments. This industrialization in South Africa meant a demand for more African workers. During 1939-49 the number of Africans in the private manufacturing industry grew from 126,000 to 292,000.

南アフリカの製造部門は帝国主義の支配力が緩んだ第二次大戦の間に急速に成長し、英国と米国が主に武器の製造に力を入れざるを得なくなったので、消費物資を外国から調達する必要に迫られました。こうして南アメリカの工業化は進みますが、その結果、もっとたくさんのアフリカ人労働者が必要になりました。1939年から49年の間に、私有の製造産業でのアフリカ人の数は126,000人から292,000に増加しました。

The new industries tried to attract labour by offering the African workers higher wages than they got in the mines and or the farms. But the white-owned agriculture had also expanded enormously during the War. And neither the farmers nor the mine owners were prepared to raise the African wages to compete with those in the manufacturing industry. Instead, they demanded a state regulated labour market, which would guarantee them a steady flow of cheap African labour.

新たな産業は、アフリカ人労働者が鉱山や農場でもらうよりも高い賃金を出して労働者を引きつけようとしました。しかし、白人所有の農業も大戦中に著しく拡大していました。そして、農場や鉱山を所有する人たちは製造産業の賃金と張り合ってアフリカ人の賃金を上げるつもりはありませんでした。代わりに、国が規制する労働市場、つまり自分たちに常に一定の安価なアフリカ人労働者を保証するように国に要求しました。

The whites in the new industries felt that their position was threatened by the African workers. They had learnt to put their trust in the Afrikaner nationalists, because they had given them job security and privileges when they started a state-controlled industrialization process before the War, with state-owned steel production, among other things. Within the state sector the white employees, unlike the African workers, were guaranteed security and benefits by clauses on positions reserved for whites. For those Afrikaners who had become impoverished when mining capital expanded and bought land, racial discrimination became their only barrier against falling to the very bottom of society.

新しい産業で働く白人は、自分たちの地位がアフリカ人労働者によって脅かされていると感じました。白人労働者は民族主義的なアフリカーナーを信用していました。というのも、第二次大戦前に国が主導して産業化の政策を進めたとき、中でも特に国有の製鉄の政策を始めたとき、自分たちに仕事を保証し、特権を与えてくれていたからです。

国有部門で白人の雇用者は、アフリカ人労働者と違って、白人専用に確保された法律上の身分条項によって、安全と利益が保証されていました。貧しくなっていたそういったアフリカーナーにとって、鉱山資本が手を広げて土地を購入したとき、人種差別が社会の最底辺に落ちないための唯一の防壁となりました。

THE POLICIES OF APARTHEID アパルトヘイト政策

The Afrikaans word apartheid means separation in English. It was the slogan in the National Party campaign. They saw a future where whites and Africans would live completely separate, and 'develop their distinct character.’ But in reality no real separation would or could be sought, because African labour power was needed as the basis for the prosperity of the whites. (See Appendix South Africa 2)

アフリカーンス語のアパルトヘイトは、英語では隔離を意味します。アパルトヘイトは国民党の選挙活動のスローガンでした。国民党は白人とアフリカ人が完全に別々に暮らし、「それぞれの特性をのばす」という将来を夢見ていました。しかし、現実には、アフリカ人の労働力が白人が繁栄するための基礎として必要でしたから、本当の意味での隔離は考えられませんし、実際には不可能です。

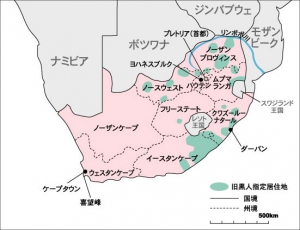

More than three million African workers and 2.5 million African domestic servants live in the 'white’ areas. Three-quarters of the wage employees in South Africa are Africans. The National Party soon admitted that the separation was to be separate sets of political and civil rights for blacks and whites. Every African had citizen rights only in the bantustan area of his own 'tribe’ whether or not he had set foot there. The nine African reserves or bantustans in reality consisted of a large number of scattered land areas, mostly barren areas suffering from land erosion and poverty. These bantustans functioned as large labour reserves for the 'white’ areas.

「白人」地域には300万人以上のアフリカ人労働者と250万人のアフリカ人のボーイやメイドが暮らしています。南アフリカの賃金雇用者の4分の3がアフリカ人です。国民党はすぐに、隔離は黒人と白人それぞれ別々の政治的な権利や市民権であるということを認めました。今まで足を踏み入れたことがあってもなくても、すべてのアフリカ人は、自分たち自身の「部族」のバンツースタン地域でのみ、市民権がありました。現に、9つのアフリカ保留地、すなわちバンツースタンは多くの飛び地から成り、そのほとんどが土地が浸食されたり、貧困に喘ぐ不毛の土地です。それらのバンツースタンは「白人」地域のために無尽蔵の労働力を確保する土地として機能しています。

The bantustan policy meant that Africans were to be prevented from living permanently in the white areas. Ruthless, forced evictions took place to force 'surplus labour’ to move from the towns to the bantustans. Crossroads outside Cape Town is only one example of this policy.

バンツースタン政策は、アフリカ人を白人地区で永住させないという意味のものでした。冷酷で、強制的な立ち退きが、「余剰労働力」を町からバンツースタンに強制的に移動させるために強行されました。ケープタウン郊外のクロスローヅはこの政策の一例です。

REFERENCE 3 参照3

We can hear the news of Radio South Africa about the 1978 Crossroads eviction in the following scene of Cry Freedom.

Newscaster: “This is the English language service of Radio South Africa. Here is the news read by Magness Rendle. Police raided Crossroads, an illegal township near Cape Town early this morning after warning this quarter to evacuate this area in the interests of public health. A number of people were found without work permits and many are being sent back to their respective homelands. There was no resistance to the raid and many of the illegals voluntarily presented themselves to the police. The Springbok ended . . ."

米国映画「遠い夜明け」の以下の場面で、1978年のクロスローヅの立ち退きについての南アフリカのラジオニュースが出てきます。

ニュースキャスター:「こちらは南アフリカラジオの英語放送です。

マグネス・レンドルがニュースをお伝えします。公衆衛生の見地から、その地域を空け渡すように勧告を出したあと、今朝早く警察は、ケープタウン郊外の不法居住地区クロスローヅの手入れを敢行しました。多くの人が労働許可証を持たず、それぞれのリザーブに送り返されています。手入れに対して全く抵抗の気配もなく、不法滞在者は自発的に警察署に出頭していました。放送を終わります・・・。」

The hated section 10 in the Native Laws Amendment Act from 1952 rule that no African could visit a place outside his reserve for more than 72 hours, unless he could prove that he had lived there since birth, or had worked in the same area for the same employer for at least ten years, or had legally resided in the same area for 15 years, or was the wife or child under 16 of a person with these qualifications. Residence permits could also be given by labour bureaus. But even those who fulfilled these requirements could be deported at any time as 'superfluous.’

1952年に制定された一般法修正令の忌まわしい第10(節)条には、生まれてからずっとそこに住んでいたか、あるいは、少なくとも10年間同じ雇用者の同じ場所で働いていたか、あるいは、合法的に15年間同じ土地に住んでいたか、あるいは、それらの資格がある人の妻か16歳以下の子供であるかが証明出来ない限り、アフリカ人は72時間以上は自分のリザーブ外の土地を訪れることができないと規定されています。労働局が居住許可証を発行出来ました。しかし、それらの資格を満たしている者でも、いつでも「余剰者」として追放されました。