<連絡事項>

来週30日も3コマ目(5~6限)と4コマ目(7~8限)の2コマ続きです。教室は3コマ目L207、4コマ目L111。(7月25日=最終日の休講分の振り分けです)

6・7回目の授業でした。

<今回>は

最初にコメント(後藤さん、佐藤くん、鮫島くん、田中さん、塚元くん、外岡くん、中川くん、中峯くん)を聞き、甲斐くんのTHE APARTHEID REGIMEとTHE POLICIES OF APARTHEIDの発表、市谷さんのMASS MOBILIZATION AND OPPRESSIONとTHE ARMED STRUGGLEの発表を聞き、最後に「アフリカの蹄」を観てもらいました。

コメントは、もっといろいろ話をしてくれると名前も覚えやすいけどねえ。

発表は、甲斐くんも市谷さんも、しっかり調べて、いい発表で感心しました。英語に関しては、下に日本語訳を貼っておくんで細かいところは参照してや。さっと英文を読んで解説はするつもりです。

支配階級(3%ほど)は自分の富を増やしたり守ったりするのに何でもする、何でもしてきた、人身売買(奴隷貿易)も人種差別も何でも利用してきた、という話を中心にしました。

感想文などを見ても人種差別は~というコメントが多いけど、人種差別は可能な限り搾取出来るように最低賃金を抑えるという制度の問題、南アフリカの場合は、大多数のアフリカ人の賃金を据え置き、アフリカーナーのプアホワイトを優遇して、その間にカラーラインをひいた、それが南アフリカの場合はapartheidアパルトヘイト、アフリカ南部の場合はsegregation人種隔離、そのカラーラインを守るための政策としては南アフリカの場合、法律でcivilized labour(賃金の高い仕事)と決めて白人に職場を確保、それに反対する者は政府が様々な法律で厳しく統制する、それが実態でした。

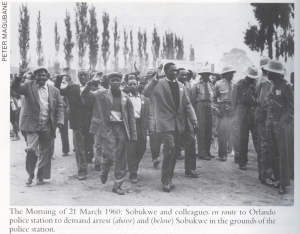

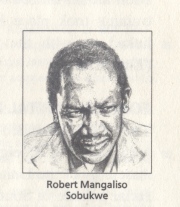

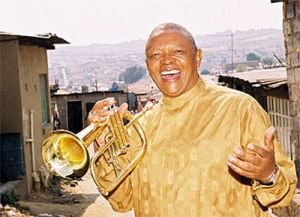

それとアパルトヘイトに立ち向かったソブクエの話と学生運動で他の人の起点になった山本義隆さんの話も少ししました。ソブクウェについては次回詳しく話をしたいと思っています。日本ではほとんど誰も紹介していないのであまり知られてないけど、歴史の分岐点の鍵を握る人物やったと思います。白人政権は先進国特にアメリカ、イギリス、フランス、西ドイツ、日本と手を携えて体制を守りました。ソブクウェはマンデラよりも早くロベン島に拘禁され、54歳で肺がんで死ぬまで自宅拘禁を強いられました。白人政府は一番体制に脅威を与える人物を完全に閉じ込めるのに成功したわけです。詳しくは↓に書いています。ソブクウェの良き理解者であったベンジャミン・ポグルンドもロンドンに亡命したあとソブクウェの伝記を出しました。この二十年の間に、感動を覚えながら読んだ数少ない本で、是非ともソブクウェについて書きたいと思いました。

→「ロバート・ソブクウェというひと ① 南アフリカに生まれて」(「ゴンドワナ」20号14-20ペイジ、1993年)

→「ロバート・ソブクウェというひと ② アフリカの土に消えて」(「ゴンドワナ」21号6-19ペイジ、1994年)

「アフリカの蹄」は帚木蓬生(ははきぎ ほうせい )の小説を脚本化したテレビドラマで、元は前編後編各90分、NHKのBSで放送されたものをビデオで録画してDVDにしました。通して観たい人はいつでもコピーするんで、遠慮なくどうぞ。国の金もたくさん投入されてるのに、こんないい映画がアーカイブでも見られないのはNHKちゃんと仕事しとらんやろといいたいとこやね。授業で使おうと思って予約録画したけど、今となっては貴重な映像やなあ。

<次回>は

3コマ目は、トーイックTest 1 Part 5(Listeningの4種類のうちの一つ)英文の穴埋め問題(4択)。サンプル5題、問題40計45題です。文法問題なんで、わかるかわからないか、ここで時間が稼げるとあとの長文問題に時間が割けます。最初に受けた人で最後の長文問題を白紙で出す人も結構いるようですが。

4コマ目は、アパルトヘイト政権、政策、解放運動などの歴史を映像で辿り、歌も紹介出来ればと思っています。アパルトヘイト政権と日本の関係、名誉白人についても触れたいと思います。時間があれば、ヨーロッパ移民が作り上げた短期契約の搾取機構、行って実際に暮らしてみたらほんまやったというハラレの話も出来れば。

それと、どうしてアパルトヘイト政権を廃止したのか、についても考えてきて、みんなで意見の遣り取りが出来ればええなあ。

今日は配ったプリントも多かったね。

* ラ・グーマとミリアムさんについて(今日市谷さんの発表で出て来た女性の日に宮崎に来られた女性作家で、知り合った新聞記者の川原さんが取材したものです。川原さんは二足のわらじははけないからと朝日新聞をやめて土呂久問題で被害者のたもに闘ってきた人。今朝日新聞の日曜日の宮崎版に土呂久についての連載をやってはります。)

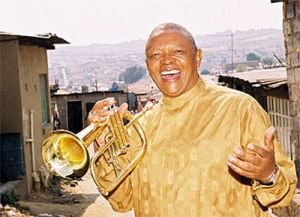

* ラ・グーマとマセケラ

* グレースランド(何曲か紹介するつもりです。)

* 5文型と品詞、用言と体言・句と節

* 副詞

* 分詞(Listening Part 5の問題をやるときに解説するんで、予め読んでおくとわかりやすいやろな。)

* 帚木蓬生と山本義隆

* 帚木蓬生

* 「アフリカの蹄」の感想文(次回出してや。)

****************

甲斐くんと市谷さんのやってくれたところの日本語訳です。

THE 1948 APARTHEID REGIME 1948年のアパルトヘイト政権

African resistance put a strain on the white alliance of the Afrikaners and the British, and created a crisis in the South African system. Social changes lay behind the increased African militancy, and the ruling party, close to mining capital, was unable to handle the situation.

アフリカ人が抵抗したので、アフリカーナーと英国人による連合政権は緊迫し、南アフリカの制度は危機的な状況に陥りました。アフリカ人がますます激しく抵抗する背景には様々な社会変化があり、鉱山資本に近い与党は、その状況にうまく対処出来なくなりました。

The manufacturing sector in South Africa grew rapidly during the War when the hold of imperialism loosened, and Britain and the United States needed consumer goods from abroad because their own production was focused on manufacturing armaments. This industrialization in South Africa meant a demand for more African workers. During 1939-49 the number of Africans in the private manufacturing industry grew from 126,000 to 292,000.

南アフリカの製造部門は帝国主義の支配力が緩んだ第二次大戦の間に急速に成長し、英国と米国が主に武器の製造に力を入れざるを得なくなったので、消費物資を外国から調達する必要に迫られました。こうして南アメリカの工業化は進みますが、その結果、もっとたくさんのアフリカ人労働者が必要になりました。1939年から49年の間に、私有の製造産業でのアフリカ人の数は126,000人から292,000に増加しました。

The new industries tried to attract labour by offering the African workers higher wages than they got in the mines and or the farms. But the white-owned agriculture had also expanded enormously during the War. And neither the farmers nor the mine owners were prepared to raise the African wages to compete with those in the manufacturing industry. Instead, they demanded a state regulated labour market, which would guarantee them a steady flow of cheap African labour.

新たな産業は、アフリカ人労働者が鉱山や農場でもらうよりも高い賃金を出して労働者を引きつけようとしました。しかし、白人所有の農業も大戦中に著しく拡大していました。そして、農場や鉱山を所有する人たちは製造産業の賃金と張り合ってアフリカ人の賃金を上げるつもりはありませんでした。代わりに、国が規制する労働市場、つまり自分たちに常に一定の安価なアフリカ人労働者を保証するように国に要求しました。

The whites in the new industries felt that their position was threatened by the African workers. They had learnt to put their trust in the Afrikaner nationalists, because they had given them job security and privileges when they started a state-controlled industrialization process before the War, with state-owned steel production, among other things. Within the state sector the white employees, unlike the African workers, were guaranteed security and benefits by clauses on positions reserved for whites. For those Afrikaners who had become impoverished when mining capital expanded and bought land, racial discrimination became their only barrier against falling to the very bottom of society.

新しい産業で働く白人は、自分たちの地位がアフリカ人労働者によって脅かされていると感じました。白人労働者は民族主義的なアフリカーナーを信用していました。というのも、第二次大戦前に国が主導して産業化の政策を進めたとき、中でも特に国有の製鉄の政策を始めたとき、自分たちに仕事を保証し、特権を与えてくれていたからです。国有部門で白人の雇用者は、アフリカ人労働者と違って、白人専用に確保された法律上の身分条項によって、安全と利益が保証されていました。貧しくなっていたそういったアフリカーナーにとって、鉱山資本が手を広げて土地を購入したとき、人種差別が社会の最底辺に落ちないための唯一の防壁となりました。

THE POLICIES OF APARTHEID アパルトヘイト政策

The Afrikaans word apartheid means separation in English. It was the slogan in the National Party campaign. They saw a future where whites and Africans would live completely separate, and 'develop their distinct character.’ But in reality no real separation would or could be sought, because African labour power was needed as the basis for the prosperity of the whites. (See Appendix South Africa 2)

アフリカーンス語のアパルトヘイトは、英語では隔離を意味します。アパルトヘイトは国民党の選挙活動のスローガンでした。国民党は白人とアフリカ人が完全に別々に暮らし、「それぞれの特性をのばす」という将来を夢見ていました。しかし、現実には、アフリカ人の労働力が白人が繁栄するための基礎として必要でしたから、本当の意味での隔離は考えられませんし、実際には不可能です。

More than three million African workers and 2.5 million African domestic servants live in the 'white’ areas. Three-quarters of the wage employees in South Africa are Africans. The National Party soon admitted that the separation was to be separate sets of political and civil rights for blacks and whites. Every African had citizen rights only in the bantustan area of his own 'tribe’ whether or not he had set foot there. The nine African reserves or bantustans in reality consisted of a large number of scattered land areas, mostly barren areas suffering from land erosion and poverty. These bantustans functioned as large labour reserves for the 'white’ areas.

「白人」地域には300万人以上のアフリカ人労働者と250万人のアフリカ人のボーイやメイドが暮らしています。南アフリカの賃金雇用者の4分の3がアフリカ人です。国民党はすぐに、隔離は黒人と白人それぞれ別々の政治的な権利や市民権であるということを認めました。今まで足を踏み入れたことがあってもなくても、すべてのアフリカ人は、自分たち自身の「部族」のバンツースタン地域でのみ、市民権がありました。現に、9つのアフリカ保留地、すなわちバンツースタンは多くの飛び地から成り、そのほとんどが土地が浸食されたり、貧困に喘ぐ不毛の土地です。それらのバンツースタンは「白人」地域のために無尽蔵の労働力を確保する土地として機能しています。

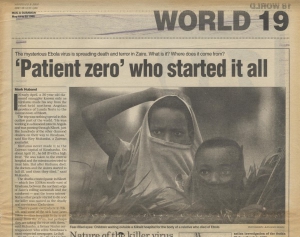

The bantustan policy meant that Africans were to be prevented from living permanently in the white areas. Ruthless, forced evictions took place to force 'surplus labour’ to move from the towns to the bantustans. Crossroads outside Cape Town is only one example of this policy.

バンツースタン政策は、アフリカ人を白人地区で永住させないという意味のものでした。冷酷で、強制的な立ち退きが、「余剰労働力」を町からバンツースタンに強制的に移動させるために強行されました。ケープタウン郊外のクロスローヅはこの政策の一例です。

REFERENCE 3 参照3

We can hear the news of Radio South Africa about the 1978 Crossroads eviction in the following scene of Cry Freedom.

Newscaster: “This is the English language service of Radio South Africa. Here is the news read by Magness Rendle. Police raided Crossroads, an illegal township near Cape Town early this morning after warning this quarter to evacuate this area in the interests of public health. A number of people were found without work permits and many are being sent back to their respective homelands. There was no resistance to the raid and many of the illegals voluntarily presented themselves to the police. The Springbok ended . . ."

米国映画「遠い夜明け」の以下の場面で、1978年のクロスローヅの立ち退きについての南アフリカのラジオニュースが出てきます。

ニュースキャスター:「こちらは南アフリカラジオの英語放送です。

マグネス・レンドルがニュースをお伝えします。公衆衛生の見地から、その地域を空け渡すように勧告を出したあと、今朝早く警察は、ケープタウン郊外の不法居住地区クロスローヅの手入れを敢行しました。多くの人が労働許可証を持たず、それぞれのリザーブに送り返されています。手入れに対して全く抵抗の気配もなく、不法滞在者は自発的に警察署に出頭していました。放送を終わります・・・。」

The hated section 10 in the Native Laws Amendment Act from 1952 rule that no African could visit a place outside his reserve for more than 72 hours, unless he could prove that he had lived there since birth, or had worked in the same area for the same employer for at least ten years, or had legally resided in the same area for 15 years, or was the wife or child under 16 of a person with these qualifications. Residence permits could also be given by labour bureaus. But even those who fulfilled these requirements could be deported at any time as 'superfluous.’

1952年に制定された一般法修正令の忌まわしい第10(節)条には、生まれてからずっとそこに住んでいたか、あるいは、少なくとも10年間同じ雇用者の同じ場所で働いていたか、あるいは、合法的に15年間同じ土地に住んでいたか、あるいは、それらの資格がある人の妻か16歳以下の子供であるかが証明出来ない限り、アフリカ人は72時間以上は自分のリザーブ外の土地を訪れることができないと規定されています。労働局が居住許可証を発行出来ました。しかし、それらの資格を満たしている者でも、いつでも「余剰者」として追放されました。

MASS MOBILIZATION AND OPPRESSION 大衆動員と抑圧

Despite severe oppression the ANC continued to work openly. But it soon abandoned its former policy of deputations and petitions, and launched a new phase of mass actions. The adoption of the Programme of Action in 1949 signalled this new stage in the struggle, and the next years showed a capacity for militancy among the black population.

厳しい抑圧にもかかわらず、アフリカ民族会議は公然と活動を続けました。しかし、アフリカ民族会議すぐにそれまでのように代表者を派遣したり懇願するのはやめて、大衆行動という新しい段階に突入しました。1949年の行動綱領の採択は解放闘争の新しい段階の前触れで、その後の何年かで、アフリカ人が積極的に闘う能力があることが証明されました。

In 1953 the ANC started to prepare a large national conference with representatives from all racial groups and from various organizations. In contrast to the all-whie parliament in Cape Town this conference was to express the will of the whole South African people. A large number of meetings were held in towns, factories, and on farms to formulate proposals for delegates and for the conference declarations. On 25 and 26 June 1955 more than 2,850 delegates from all over South Africa gathered in Kliptown outside Johannesburg and, after discussions, adopted the Freedom Charter.

1953年に、アフリカ民族会議はすべての人種グループと色々な組織の代表者による大規模な国民会議の準備を始めました。ケープタウンでの白人だけによる議会とは対照的に、この議会は、すべての南アフリカの人々の意思を表わしたものでした。たくさんの会議が町や工場や農場で行なわれ、代表と会議の宣言のための草案が作られました。1955年6月25日と26日に、南アフリカじゅうの2850人以上の代表者がジョハネスバーグ郊外のクリップタウンに集まり、議論の末に、自由の憲章が採択されました。

This document opens with the words, 'We, the people of South Africa, declare for all our country and the world to know: that South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white, and that no government can justly claim authority unless it is based on the will of the people . . .’ It also says that land shall ` be shared among those who work it, that the doors of learning and culture shall be open to all, and that the mineral wealth, the banks and monopoly industry shall be transferred to the people as a whole. The organizations which had arranged the Kliptown conference joined to form the Congress Alliance. It consisted of the ANC, the South African Indian Congress, the South African Coloured People’s Congress, the Congress of Democrarts (a white organization), and the trade union central body SACTU (the South African Congress of Trade Unions). The SACP worked under- ground ever since it was banned in the early 1950s.

この憲章は以下の言葉で始まります。「私たち南アフリカ人民は、すべての国と世界に知ってもらえるように宣言します。南アフリカは黒人も白人も、そこに住む人々に属し、人々の意志に基づかないない限り、どんな政府も公正に権利を主張できない、と・・・。」また、土地はそこで働いている人たちの間で分配され、学問や文化の門戸はすべての人に開かれ、豊かな鉱産資源や銀行や独占企業はひとまとめで人々の手に引き渡すと宣言しました。クリップタウン会議に参加した組織は会議運動を形成しました。それはANC、南アフリカインド人会議、南アフリカカラード人民機構、民主主義者会議(白人の組織)、そして労働組合の本体SACTU(南アフリカ労働組合会議)で構成されていました。SACP(南アフリカ共産党)は1950年代初期に活動禁止処分を受けて以来、地下活動を行ないました。

REFERENCE4 参照4

Benjamin Pogrund, a South African journalist, introduced the PAC major aims listed by Sobukwe and five aims adopted by the Congress in his book Sobukwe and Apartheid:

南アフリカの新聞記者ベンジャミン・ポグルンドは、ソブクウェが挙げたPACの主な目的と、国民会議で採択された5つの目標を著書『ソブクウェとアパルトヘイト』の中で紹介しています。

“Sobukwe listed three major aims: firstly, politically, `the government of the Africans, by the Africans, for the Africans, with everybody who owes his only loyalty to Africa and who is prepared to accept the democratic rule of an African majority being regarded as an African. We guarantee no minority rights because we think in terms of individuals not groups.’ Secondly, `economically we aim at the rapid extension of industrial development in order to alleviate pressure on the land which is what progress means in terms of modern society. We stand committed to a policy guaranteeing the most equitable distribution of wealth.’ Thirdly, `socially we aim at the full development of the human personality and the ruthless outlawing of all forms of manifestations of the racial myth.’ "

「ソブクウェは主な三つの目標をあげました。第一に、政治的にはアフリカに忠誠心を置き、誰もがアフリカ人として大多数のアフリカ人の民主主義的な支配を快く受け入れる、アフリカのための、アフリカ人による、アフリカ人の政府。集団として見なすのではなく、個人として考えるので、少数派の権利は保証しません。」第二に、「経済的には、土地への抑圧を減らすために、産業の発展を急速に拡大させるつもりです。現代社会ではそれが進歩を意味しますので。富の最も公平な分配を保証する政策も推進する方針です。」第三に、「社会的には、各個人の人間性の十分な発達と、あらゆる種類の明らかな人種差別を法律的に徹底的に排除したいと考えます。」

“Five aims were adopted: `(a) to unite and rally the African people into one national front on the basis of African Nationalism; (b) to fight for the overthrow of white domination, and for the implementation and maintenance of the right of selfdetermination for the African people; (c) to work and strive for the establishment and maintenance of an Africanist Socialist democracy recognising the primacy of the material and spiritual interests of the human personality; (d) to promote the educational, cultural and economic advancement of the African people; (e) to propagate and promote the concept of the Federation of Southern Africa, and Pan Africanism by promoting unity among peoples of Africa.’ "

「五つの目標が採択されました。「(a) アフリカナショナリズムを基に、アフリカ人民をある国民前線に団結させ、集めること。(b) 白人支配打倒と、アフリカ人の自己決定権の実現と維持のために闘うこと。(c) それぞれの物質的、精神的利益が最も大切あると認め、アフリカの社会民主主義の確立と維持のために働き、闘うこと。(d) アフリカ人の教育、文化、経済の向上を奨進すること。(e) アフリカの民族間の統合を推進して、南部アフリカ連合とパンアフリカニズムの概念を普及し、奨励すること。」

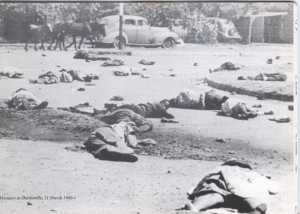

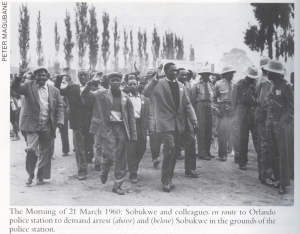

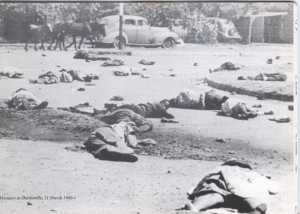

In 1959 the ANC decided to organize a mass protest against the pass laws. The protest was going to begin on 31 March 1960. In the same year the PAC drew up a plan to campaign for freedom for South Africa by 1963. The PAC campaign began on 21 March 1960. On the day thousands of people gathered at the police station in Sharpeville Township. The police opened fire, and 69 people were shot dead. This became known as the `Sharpeville massacre.’ On the day, Sobukwe and other leaders were arrested.

1959年に、ANCはパス法に反対して大規模な抗議運動を計画することを決めました。抗議運動は1960年の3月31日に始まる予定でした。同じ年に、PACは1963年までに南アフリカの独立を求める運動を展開する計画を立てました。PACの抗議運動は、1960年の3月21日に始まりました。その日、数千人の人がシャープヴィルの警察署に集まりました。警察は発砲し、69人を射殺しました。これは「シャーペビルの大虐殺」として知られるようになりました。その日に、ソブクウェと他の指導者たちは逮捕されました。

THE ARMED STRUGGLE 武力闘争

The Sharpeville massacre became the turning point. The ANC and the PAC were banned and forced to start an armed struggle. In 1961 the ANC formed an army called `Umkhonto we Sizwe’ (`the Spear of the Nation’) and the PAC formed a secret army called `Po(g)qo’ (`Alone’). The Umkhonto began to blow up pass offices and electricity power-lines, while the Poqo began to attack chiefs and policemen. But in 1963 the police arrested their leaders. By 1964 all of them, including Nelson Mandela, were imprisoned. A period of decline followed. Many leading activists had to flee the country to escape arrest. The work underground proceeded but with great difficulties. Open actions could not be carried out. By 1965 the armed struggle had been crushed. The PAC and the ANC were forced to continue their armed struggle from outside South Africa. The parties’ leadership and liberation armies moved to Zambia and Tanzania and their military training took place in Africa and overseas. They sometimes linked up with the liberation armies in Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe).

シャープビルの大虐殺は転機点になりました。ANCとPACは非合法化され、武力闘争を開始せざるを得ませんでした。1961年にANCは「ウンコントウェシズウェ」(民族の槍)と呼ばれる武力闘争部門を創設し、PACは「ポコ」(単独で)と呼ばれる秘密の武力組織を作りました。ウムコントはパス(通行証)管理局や送電線を破壊し、ポコは首長(チーフ)や警察官の襲撃を始めました。しかし1963年に、警察は両組織の指導者を逮捕しました。1964年までに、ネルソン・マンデラを含むすべての指導者が投獄されました。衰退の時期が続きました。多くの指導的立場にいた活動家が、逮捕を逃れれて国外に逃亡しました。地下活動は続きますが、非常に困難を極めました。公の活動は実行出来ませんでした。1965年までに、武力闘争は抑えこまれました。PACとANCは南アフリカの外から武力闘争を続けざるを得ませんでした。党の指揮権や解放軍はザンビアやタンザニアに移り、軍隊訓練はアフリカや海外で行なわれました。両者は時々、南ローデシアの解放軍と連携しました。