概要

ラ・グーマの初期の作品に見られる文学手法に焦点をあてた作品論です。抑圧の厳しい社会では政治と文学を切り離して考えることは出来ませんが、作者の文学技法によって作品を政治的な宣伝でなく文学として昇華させるのは可能です。ラ・グーマの使うリアリズムとシンボリズムの手法が、読者に期待感を抱かせる役割を果たしている点を指摘しました。

本文(写真作業中)

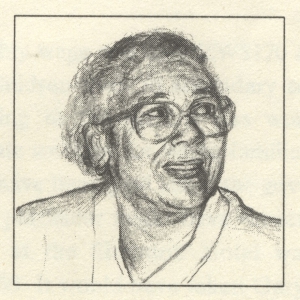

When Alex La Guma was asked, in an interview, “What do you think of symbolism as a literary device?" he answered, “I have no objection as long as the reader knows how to interpret it correctly. In my novels there is a combination of realism and of transparent symbolism."1

In this paper I would like to give an estimation of realism and transparent symbolism in La Guma’s works, especially in his first two novels A Walk in the Night and And a Threefold Cord.

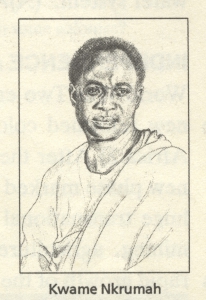

Needless to say, “one cannot separate literature from life, from human experience and human aspiration."2 That is even more true for Alex La Guma, living in such an abnormal situation where even writers, if necessary, must fight against the oppressors with guns in hand. In South Africa, people were forced to be engaged in a human rights movement, not a civil rights movement as in the United States, because the laws of the country themselves were discriminatory and they could not expect protection and support from their Constitution. They were forced to give up non-violent strategies because the white regime did not have the essential minimum moral standards. History verifies that. La Guma “finds himself with no other choice but to dedicate himself to that movement which must involve not only himself but ordinary people as well."3 He creates his novels in the midst of his liberation struggle, but they are not propaganda or slogans for the struggle. The following interview conveys to us his intention:

- What are then the values which you seek to express in your novels?

La Guma: I want to express the dignity of people, the basic human spirit in the least pompous way possible. One must avoid propaganda or slogan. I am also politically involved. In my writing and in my political activities I vindicate the dignity of man, but these are two different activities.4

It is his artistry that enables him to avoid polemical stances in his creative writing. These beliefs have led him to choose realism and transparent symbolism as literary devices, on the presumption that the reader knows how to interpret the South African situation correctly. He once observed in an article:

One of the greatest values of literature is that in deepening our consciousness, widening our feeling for life, it reminds us that all ideas and all actions derive from realism and experience within social realities.5

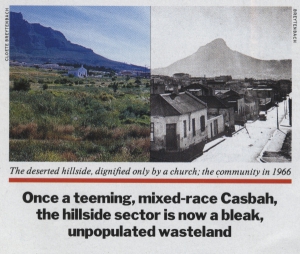

From his keen desire for “at least letting the world know what is happening,"6 in South Africa, he describes in his stories characteristic scenes in the cities and the suburban slums.

A Walk in the Night is centered on two blacks7 on the verge of criminality, Michael Adonis and Willieboy, and an Afrikaner policeman, Raalt. These are typical and important thematic characters of the South African predicament.

Adonis loses his job by answering back to a white foreman, which frustrates and angers him. His anger and frustration drive him into killing a poor old white neighbour, Uncle Doughty. This act finally makes him get involved in the underground. Through Adonis’ gradual degradation, La Guma shows us how inevitably an ordinary youth gets drawn into illegalism.

Willieboy grows up in a broken family, but takes life very easily and is always unemployed, claiming that it is useless to work for anyone. One day he calls un Adonis, but finds himself wrongly suspected of the murder of Uncle Doughty. He is pursued by Raalt and finally shot to death. Through Willieboy’s tragic fate La Guma hints to us how easily and vainly criminal activity can shorten one’s life.

In And a Threefold Cord we find another kind of gangster called Roman. Roman was once an ordinary worker, but after going through various menial jobs, he takes to petty thieving and finally ends up in jail. In his kennel-like shack, he cannot support his family and they are constantly hungry. In a state of drunken savagery he regularly beats his wife and whips his eleven children, until his wife goes beyond hatred for him. Roman is a typical petty criminal, who compensates for his wretchedness by attacking weaker ones around him.

In that sense Raalt, in A Walk in the Night, is similar in attitude to Roman. Raalt feels dissatisfied with his marital life and resentful of his wife. He tries to discharge his anger and frustration by ill-treating black citizens. While on patrol he longs for anything to happen to release his tension. Unfortunately his gunpoint is directed by chance towards Willieboy. His hunting of Willieboy is relentless; he finally corners him and shoots him mercilessly. He refuses to allow an ambulance to take the dying youth to hospital. He tops off his brutality by dropping in at a store to extort cigarettes, while Willieboy is dying in the police van.

Another disturbing scene involving the white police is found in the same story. On his way home Adonis is confronted by two strolling policemen, who accuse him of having marijuana. He denies the accusation, and they order him to turn out his pockets. “They find his money and accuse him of having stolen it. But in the end they cannot find anything to charge him with, so they push past him, one of them brushing him aside with his elbow, and stroll on away. It is only because he came across them on the street that he was accused. All of this happens in the presence of passers-by in broad daylight.

The same kind of brutality by white policemen figures in And a Threefold Cord. On a pass raid a white policeman with two Africans breaks into a shanty by kicking the door open with his muddy boot. A couple are lying naked in bed. Finding that the man has no pass book, he puts handcuffs on him and takes him out into the falling rain after jerking the blanket from the woman’s naked body. She begins to weep with a high, wailing sound.

In the night raid on his sweetheart Freda’s shanty, when he is staying with her, Charlie is unjustly accused of having marijuana by a white policeman. Freda is humiliated by being sworn at, “Blerry black whore." Her children begin to wail with terror.

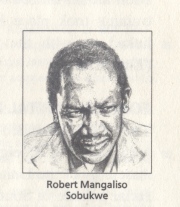

Such scenes of inhumanity clearly convey to the reader the harsh reality of a police state which continually harasses black people in everyday life. “The violent scenes make it quite plain that for the white regime even the Sharpeville Massacre in 1960 was just another everyday incident.

Through his true–to-life description La Guma raises a serious dynamic. The more brutal white people become, the more the hatred of black people intensifies. Their gap widens and deepens more and more. They are fated never to attain mutual understanding. In that sense they are both victims of the monster apartheid, because they are permanently at the mercy of the socioeconomic and political environment. If we borrow some words from Shakespeare, some of which are found in the epigraph of this story, brutal whites and hopeless blacks are both “just ghosts, doomed to walk the night." like Hamlet’s father. Thus we can say that the night, haunted both by blacks and whites roaming aimlessly and despairingly, is one of the transparent symbols of this abnormal, segregated society.

In A Walk in the Night La Guma concentrates on the negative side of the society, but in And a Threefold Cord he gives attention to the positive side of the oppressed people.

The story proceeds through the consciousness of Charlie Pauls, the protagonist, and through the experiences of his family and its associates. A number of incidents occur in this story, two of which especially affirm the reality of an oppressed people who are managing to sustain a community even under the severest conditions of apartheid. One incident is Charlie’s father’s death and the other is the birth of his sister’s child. The situation tells us the importance of a “threefold cord" relationship, which means helping each other and living in harmony with love, as is indicated in the epigraph.

Charlie’s father, Frederick Pauls, has worked continually for his family but finally becomes bedridden with illness. Their shabby shanty and meagre food make him worse until at last he dies, all skin and bones. The only sounds from him throughout the story are his moans and coughs in his bed. Through his wife, Rachel, the reader catches his first and final words; “Rachy,…,…is the children awright?… I would have liked them to be living in another place. Like those houses with the roofs."8 The sickness forces him to lie in bed in a dark room with a ceiling stained by constant leaking. Day in and day out there is nothing for him to gaze at but a black map of dampness on the ceiling. He must have dreamed that he could have let his children live in a house with the roofs in which they wouldn’t have to worry about leaks. Though in agony, he continued to feel concerned about his children until his last breath. His final words suggest such sorrowful regrets. His love and sorrow for his family have been great and deep.

This is also true of Rachel. She too is a conscientious worker and carries on all the ordinary chores of a hard life. When her husband dies she does not get upset. Instead of weeping, she performs elaborate arrangements for the funeral, according to her sense of duty to consign one’s dearest reverently to the grave.

With the help of relatives and neighbours, she manages to conduct the funeral decently thanks to her contributions to burial insurance. In those scenes of Frederick’s death and the funeral we can find no actual tears from Rachel, but all her tears are expressed in her deeds. Each of her determined actions is her own way of expressing her deep love and great sorrow for her deceased husband.

Charlie’s sister, Caroline, was born in a sort of chicken-run because her father and brother could not get a shack built in time. Now she is to give birth to her baby in her miserable shanty. The rain drums down and the rainwater, leaking in, spreads across the floor. Her mother arrives in time, but not the midwife. Her mother begins to put old newspapers under Caroline’s waist. The following text shows us the nightmarish conditions of the birth:

At the moment Caroline screamed. The police raider said, ‘Ghod!’ He peered past Ma into the shack, saw Missus Nzuba’s vastness crouched over the girl on the mattress. His eyes moved about, over the smoky ceiling, the muddy floor, the leak in the roof and ragged clothes displayed as if for sale. The smell of smoke and oil and birth made the air fetid.

He said, again: ‘Baby? What, in here?’ Then he shrugged and growled, ‘Awright, awright.’ (pp. 150–151)

Though the policeman cannot believe it, Caroline has given birth to her child successfully with the help of her mother and a neighbour. As long as the social system is not changed, childbirth in such awful conditions will recur from generation to generation, and that is what this episode tells us.

Through these two incidents we realize that South African blacks manage to sustain their existence by honoring the dead and the coming generation even in the harshest conditions through mutual aid.

In the story La Guma makes effective use of rain, falling on their shanties without let-up. It is raining when Frederick Pauls breathes his last in their shanty. He passes away hearing the falling rain and gazing at the dirty ceiling stained by the leak. Death finally forces a regretful separation from his family. Though his wife well understands his disappointment, she can do nothing but look at her husband sorrowfully. When we think of his regret and her grief, it seems to us that the `stained maps’ of the leaks are a visible expression of his blighted hopes and that the falling rain outside is the expression of her tears of sorrow.

It rains heavily when the police raid Freda’s shanty. The falling rain, with its loud roar, symbolizes the fright of Freda and her children and acts to deepen an impression of the cruel policemen who storm the shack.

The ubiquitous rain envelops another shanty raid, too. In this case a white policeman with his men steps into the shanty in muddy boots and takes a naked, handcuffed African forcibly to the police van. The rain in this scene gives us an impression of the ever more merciless police.

Rain is falling again when Caroline gives birth to her baby. Its ominous roar arouses so much fear in her, alone with the labour pains, that she is afraid that she is going to die. The rain drums down and a leak opens in the ceiling. The water forms a puddle in front of the doorway and begins to spread across the floor. We become even more sympathetic to her childbirth.

The downpour also embraces Charlie’s brother, as he hacks his erstwhile girlfriend to death. He stands, soaked, over her dead body while her dead eyes stare up out of the rain-washed face. The rain emphasizes the tragedy of these two, doomed to lire out of their lives of spiritual isolation.

La Guma begins the last chapter in the same way as he did the first chapter; “In the north-west the rainheads piled up,…" and ends it with rain, too. It is a world of greyness. We see Charlie, Freda, and Rachel in their shack. Rachel and Charlie put Freda on Frederick’s bed and try to console her for the children she lost in a fire Outside the shanty the weather rages furiously. The text reads:

The rain excavated foundations and dredged through topsoil and a house sagged and tottered, battered into a jagged rhomboid of gaping seams and banging sides. The rain gurgled and bubbled and chuckled in the eaves and ran like quicksilver along the ceilings, and below, the shivering poor blew on their braziers and stoked their fires, crouched trembling with ague in the relentless dampness, huddled together for warmth and clenching their teeth against the pneumonic chattering. (p.166)

The Pauls family and their hovel are not extraordinary in the suburban slums in Cape Town. Such families and such shanties are everywhere in the country. The family, though its members each have their own troubles, manages to live on together; the shack, though sagging and tottering in the wind and rain, provides shelter to the inhabitants. In a sense the makeshift home is an exact microcosm of those slums. The shanty, weathering the storm outside, symbolizes the position of black people who are somehow making it through the ugly conditions of apartheid.

La Guma tries to compare this relentless rain to the oppressive white regime, and the miserable shanties to the plight of the people. The next passage in the final chapter is highly symbolic:

In the Pauls’ house, those inside heard the rain, but took no notice of it. It was a sound apart from the feeling of sorrow. Miraculously, the house held. Dad and Charlie Pauls and others had built it well; well enough to stand up against this kind of storm, anyway. The rain lashed at it, as if in an anger of frustration. Finding the leak in the ceiling blocked, the water steered towards the ends of the roof and seeped down the walls inside. But the house seemed to clench its teeth and cling defiantly to life. (p. 166)

It is evident that the shanty, standing up against lashing storms outside, is another transparent symbol.

According to one interview, realism is not “a mere projection of the present" for La Guma. “It must convince the reader of truth, suggest that something can happen."9

La Guma’s techniques of connecting realism with transparent symbolism carry through successfully the correlation of night and darkness with the dark truth of apartheid society, while the shanty, with its resistance to the storm, is a note of hope, suggesting indeed “that something can happen." 10

Notes

1 Richard Samin, “Interviews de Alex La Guma," in Afram Newsletter No. 24 (January 1987), p. 11.

2 Alex La Guma, “Literature and Life," in Lotus: Afro-Asian Writings 1, No. 4 (1970), p. 238.

3 Per Wastberg (ed.), The Writer in Modern Africa: African Scandinavian Waters’ Conference, Stockholm 1967 (Uppsala: Scandinavian Institute of African Studies, 1968), p. 24.

4 Samin, p. 13.

5 La Guma, “Literature and Life," p. 238.

6 Dennis Duerden and Cosmo Pieterse ed., African Writers Talking (London: Heinemann, 1972), p. 93.

7 They are the so-called ‘coloured’ youths. Some South Africans are against the usage of ‘coloured’ because the white regime used ‘divide and rule’ tactics and categorized its people into four groups: WRITE, ASIAN, COLOURED, and BLACK. When I interviewed Cecil Abrahams, La Guma’s biographer, he called La Guma and Peter Abrahams black writers, not coloured writers. So I asked, “Can’t we call them coloured writers?" He answered, “No. Today, they don’t like to be called coloured any more. Just white and black, because the government of South Africa tried to divide the black people into BLACK, COLOURED, and INDIAN." (August 22-25, 1987 in St. Catharines, Canada)

8 La Guma, And a Threefold Cord (Berlin: Seven Seas Publishers, 1964), p. 111; further quotations from this work will be cited in parentheses in this paper.

9 Samin, p. 14.

10 While he was alive, ‘something’ did not happen to him. He wasn’t able to see the birth of the new government in 1994. He was born in Cape Town in 1925. In 1966 he was forced to flee to London with his family, and never again set foot on the soil of his mother country. In 1985 he suddenly died of a heart attack in Havana, Cuba. He was only sixty years old. His wife Blanche and one of their sons are now back home in Cape Town.

This is a revised version of a paper read at the ‘English Literature Other than British and American’ session of the Modern Language Association of America in San Francisco on December 27, 1987.

(Miyazaki Medical College)

執筆年

1996年

収録・公開

「言語表現研究」12号 73-79ペイジ