概要

南アフリカの作家アレックス・ラ・グーマ(1925-1985)を知るために、カナダに亡命中の南アフリカ人学者セスゥル・A・エイブラハムズ氏を訪ねた際に行ったインタビューです。見ず知らずの日本からの突然の訪問者を丸々三日間受け入れて下さったエイブラハムズ氏の生き様、そのエイブラハムズ氏が語る「アレックス・ラ・グーマ」を録音し、帰国後聞き取り作業をしてまとめたものです。

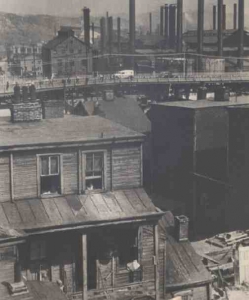

本文(写真作業中)

YOSHIYUKI TAMADA INTERVIEWS CECIL ABRAHAMS

(August 22-25, 1987 in St. Catharines, Canada)

1-A

Cecil – I’d say that in June, 1985, the Soviet Writers’ Union had a special evening for Alex La Guma in Moscow to celebrate his sixtieth birthday and they had…in the auditorium there over a thousand people came to celebrate with him. And I was one of the speakers. And I was so amazed at how many people had read La Guma. So all came to the auditorium with books under their arms for autographs and there was one man in his, probably late seventies and he was blind but his arm was full of La Guma’s books. And he came up to him to ask him to autograph it. It was a very touching experience. In fact what they did! The publishers in the Soviet Union for his sixtieth birthday brought out half a million copies of his collected works and they sold it all within one month. He is, he was a very popular writer in the Soviet Union and of course he visited there many times. Also because he was a member of the South African Communist Party. His father had been in the South African Communist Party. So there’s this connection to the Soviet Union and his books have been translated into many Soviet languages. So he is widely read and more respected in the Soviet Union. So maybe some day in Japan there will be just as many people read Alex La Guma….

Yoshi – I hope so….

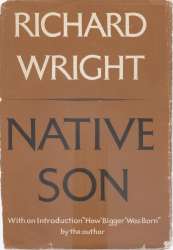

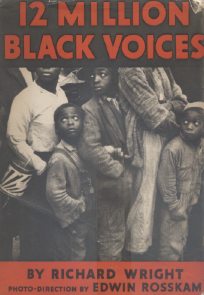

Cecil – Yeah, because for South Africa, and for South Africans, we think, among the black writers Alex La Guma’s always the best writer that has been produced by South Africa. And also because he’s written more books, more novels than any other black South Africans expect Peter Abrahams. But Peter Abrahams wrote many years ago. And he stopped writing about South Africa. He started writing about Africa in general and about Caribbean. But Alex La Guma’s five novels have made him perhaps our best writer among black South Africans. And what is important now is even though Alex La Guma was banned in South Africa, so his books could not be read by South Africans. It was not allowed to be sold. Now some South African publishers ask permission from the government to…to….

Yoshi – To publish books?

Cecil – To publish books and they think it may be possible because I had a letter just recently from Phillips Company in Cape Town and they asked me whether I could make it possible for them to publish his material again. They wanted to do A Walk in the Night. They wanted to publish it again. Maybe soon South Africans will have the opportunity to read Alex La Guma.

Cecil — He was then living in Cuba. So we did many, many discussions on the books, his life in South Africa. So while you are here, I’ll let you listen to some of them to give you an idea of what he said and so on, also to hear his voice talking about his own books and his experiences. Yes. He was very helpful, he was not…: you could ask him for anything, he’d do it for you. He was a very kind, very friendly person.

Yoshi – It is unhappy that the situation in Japan is not so good because scholars on Africa are not good. They were and are studying African materials for the sake of study. Do you know Mr. A?

Cecil – Yes.

Yoshi – He is not good. And do you know Mr. B? He is not good, either. I feel very sorry. Mr. Kobayashi was quarreling with them. They are not so good. The worst thing is that they introduce Africa in bad ways to Japanese readers….

Cecil – Well, we are now fortunate with people like Kobayashi, You. You are now taking a serious interest in South African literature and obviously, if you do your home-work and you’ve come all this way from Japan to come and ask me questions about La Guma, it means that you are serious. You want to know as much as possible. So when you begin to write about it, and introduce him to Japanese people, you’ll be speaking something from authenticity, not something that is not true. And that’ll be very helpful, because I think it for us South Africans is very important that Japan or people in Japan know about what’s exactly happening now, because Japan is a very powerful nation economically and she has quite a lot of investment in South Africa. And our aim is to try to get all the countries that invest there to stop investing, because the South African regime will continue to be as they are at the moment-if they know countries like Japan, West Germany, France, Britain, U.S.A., Canada, that they’re all supporting economically. So they’ll simply say, “there’s nothing wrong with our system, why should we change?" So we feel that, you know, these rich countries or these economically strong countries should stop investing there. Furthermore, our view is that Japanese are an Asian nation and therefore should be closer to other Third World nations especially to Africa and that we should be able to get help from Japan…. They should have no difficulty in listening to our position. It may be more difficult to convince U.S.A. or Britain because they can argue that people over there are our kith and kin, you see, but Japanese, they are not kith and kin, so why should they help? The economy is there, you see.

Yoshi – The ruling party is very conservative and now most of Japanese are Americanized and they know nothing about the situation and the ruling party is going forward to the Third World War. For example they gained the power of the advancement of security treaty between the United States and Japan. They succeeded by the majority of the Congressmen. So but most of Japanese do not recognize the dangerous situation. Only the Communist Party is stressing the dangerous situation. We may make the same error when we made the error at the Second World War. Do you support ANC?

Cecil – I am a member of ANC.

Yoshi – I’m carrying some money for ANC, but I’m having Traveler’s check, so I’d like to change the traveler’s check into cash.

Cecil – Alex La Guma located himself in a central position. He didn’t just write for writing’s sake. He wrote to tell stories about the real problems of the people in South Africa. So I think in that way his books will always be important. They’re important as stories but also important as histories. Because La Guma always talked about recording the history of South Africa.

Yoshi – You stress it in your book.

Cecil — I stress the point that he saw himself as a recorder of history. That he had to give the picture of the lives of the people in South Africa, which is very important. So I think in that way his writings will always be important. Even one day when South Africa has no more apartheid our young people will have a history of what had happened before so that we don’t repeat those mistakes in the future. Because it’s very important that we don’t replace white racism with black racism. It’s important that all our people are given democratic rights and that people are seen as human beings not human beings who are black or brown or white, but human beings who are just living and trying to make a life. And so it’s very important that we have these books so that if we have the majority of the blacks, for example, say, well, why don’t we oppress the minority? Then we can always point out, look, we’ve gone through this before and there’s no point repeating this. Alex La Guma believed very deeply in the integrity of the human beings not integrity of the black person or the white person human beings and the violation is not the violation of white or black person but of the human beings. And so in this way all his work, it was his purpose in life to try to bring about South Africa and a world, where all people are respected for their humanity not for their colour.

They are the policies of ANC.

Cecil — It’s ANC policy. ANC policy is exactly the same. That you don’t look at the person’s colour, person’s wealth, whether a person’s beautiful or ugly but you look at a person as a human being, what you offer as a human being to make it a better society, and a better world. La Guma believed in very firmly and he loved it. And I think that was one of the nice things about him -If you went to visit him, he would be very easy with you. He didn’t look at you because you came from Japan and even if Japan is not one of the countries that is a big support of ANC. La Guma doesn’t look upon you as being the country Japan. He looks upon you as another human being who is interested in the problems of South Africa, who would like to see changes that will bring about our equal society. That’s what he’s looking at. lie would disagree with you if you came to his house and said, “I don’t believe in those principles," he’ll kick you out of his house. The people who come in my house are people who believe in the principles I believe in. fn that way he was a very nice person to know and his wife is also the same. She also worked with him in the political movements. She also went to jail. So they worked together very closely and I think you see the same humanity, the same concerns coming into the books. When you tell stories in the books, they’re always stories of people, while oppressed, he is always trying to get them to fight back, to challenge the system….

When did you make friends with Alex La Guma?

Cecil — Well, I actually only met Alex La Guma outside South Africa.

Outside South Africa?

Cecil — I didn’t know him there, but I knew about him. I had read his columns in the newspaper and I’d read about him. But I didn’t know him, and I was still too young.

When were you born?

Cecil — I was born in 1940.

1940?

Cecil — Yeah, Alex La Guma was born in 1925.

I was born in 1949.

Cecil — 1949. Oh. So I did’t know him, but I was born in Johannesburg in the inner city, in a suburb called Brededorp. This suburb had been made famous by one of the first black writers called Peter Abrahams. You’ve read some of his works?

Ah, he is also a coloured man?

Cecil — Yes, he is also a coloured man.

Can I, Can we call a coloured man?

Cecil — Yes….

Is it polite?

Cecil — No, it’s not any more. Today all the people who are not white, we call black, not coloured any more.

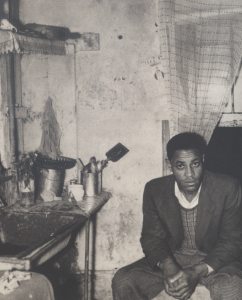

Cecil — So I was born in a home where my father came from India and my mother had a Jewish father and an African mother, a Zulu mother. So we were classed as coloured in our area by the government. And we were a poor family. There were six children. And…but my mother had a strong interest in us getting schooling, that we should get some education. She argued that if you have an education, you can take care of yourself. I lived in an area that was very poor, really poor, and so early in my life I became conscious of the inequality between white and black. So I, at the age of twelve, I went to jail for the first time.

To Jail?

Cecil — Jail. To prison. For opposing we had some sports fields, soccer fields. One side was for black children. The other side was for white children. Black children had just gravel. White children had grass. So I took all the black children into the white side.

Is it, was it difficult to play on gravel?

Cecil — Very, very, because we got scratched, and injured and so I took the children over to the white side of the grass, and we got arrested. Then I was very active in my community, helping people oppose all sorts of wrong legislation. So I went to jail three times. And I became….

How long?

Cecil — Well, each time was only a short period, for a few weeks, and I became a member of the African National Congress. When I was only sixteen, I joined ANC. And then, when I finished my high school, I went to university. The university is in your, in this magazine. The University of Witwatersrand. I went there one year but I left because….

What’s the name of….

Cecil — University of Witwatersrand. I’ll show you a picture you call it Witwatersrand.

How do you pronounce?

Cecil — It’s an Afrikaans word. It means Wit-waters-rand which means…..

Wit, Wit…

Cecil — Wit-waters-rand

Waters-rand

Cecil — It was a spelling mistake (in your magazine) Wit-waters-rand, there should be an 'r’ there, not an '1’, should be an…, it means this is the area of southern Johannesburg. It’s about thirty-six miles long and all along it they discovered gold. So it was called Witwatersrand. This is the university.

Cecil — I went there for one….

He is now….?

Cecil — Yes, that’s right. Mphahlele, yes. That’s right. I left after one year because they used to discriminate. They discriminated against us. There were students, there were five thousand students. There were about four thousand nine hundreds and fifty were white and fifty black students. We were not allowed to take part in dancing, gymnastics, sports. We were only allowed to go to class and the library. Otherwise, we weren’t allowed because we were not white. So I didn’t like it. So I left it. I went to Basotho land. Today it is Lesotho.

Lesotho, one of the homelands?

Cecil — No, not a homeland. It’s an independent country. It’s inside South Africa. L-E-S-O-T-H-O.

LESOTHO, LESOTHO….

Cecil — At that time it was not independent. It was still under British rule. It was called Basotho land. So I went to college, there. I finished my B. A. and I came back to South Africa and I taught high-school without a teacher’s certificate. So I was unqualified, but I had a degree, which was something rare, because very few black people got degrees. We were a small number. I taught high-school for seven months.

Seven months. High-school?

Cecil — Yes. I taught English and history and all sorts of things. Then I was arrested again for taking part in a “stay home." We asked the people to stay off from work, when South Africa became a republic, and I was in….

Oh, 1961?

Cecil — Yes. Then I was a…. I helped to organize the stay home, giving out leaflets, advising people not to go to work. And we were arrested. We were kept in jail for four months.

Four months.

But we were not put on trial. We were just kept. And finally they put us on trial.

For the Communist Party?

Cecil — No, by the government, they put us on trial. They said we were trying to get the people to oppose the government, to destroy the country. So when we were put on trial, the ANC, then we were let out on bail. And then the ANC decided that some of us had to leave the country because we were wasting a lot of our lives there by going to jail, so they told us we should leave the country. I first went to Swaziland, then to Tanzania and from Tanzania I was sent to Canada and in Canada I completed my studies and did my master’s degree and my Ph.D. And I….

In Canada?

Cecil — And the ANC decided it would be better for me to stay on rather than go back. By now they are calling me a communist

Like La Guma?

Cecil — Like La Guma. That’s a very common thing. When they don’t like you, they suddenly decide you are a communist. So for South Africans communism means opposing injustice. Communism means the neglect. They don’t understand communism. They only know if you oppose apartheid, then you’re a communist and that’s good. So I left and came to Canada to work with the ANC, but also to finish my studies. Then I started teaching at the university. And I’ve been teaching and working quite actively for the ANC.

Cecil — I’ve been in Canada since 1963, teaching and working with the ANC. At the beginning we had no ANC people, now we have a few working for us in Canada.

In Canada is it common foreigners can get a full time job?

Cecil — You have to be a Canadian citizen or an official immigrant. They don’t want foreigners any more. But it was quite easy up to about five years ago. In fact, many of the professors of Canada at Canadian universities are from England or from America or some Europeans. But I came to Canada as a refugee, so I had no papers, because I had no South African passport, because I’d escaped the country and so they gave me Canadian papers-so it was not a problem.

Is it easy to get a permanent visa for a South African?

Cecil — No.

No. Is it difficult….

Cecil — Is it easy for South Africans to come to Canada? It depends South Africans can come here now, and they can claim refugee status because South Africa’s having so much trouble. If you are persecuted by the government of South Africa, then Canada will give you a refugee status. If you want to come here as an immigrant, the procedure takes a long time. And generally Canada has not been favorable for immigrants that are not white. It’s much harder to get any kind of papers in Canada. So South Africans don’t come to Canada very much. So South Africans usually go to England, or to the US or in Africa to places like Zimbabwe, Tanzania, and other countries.

Zambia has the headquarter of ANC?

Cecil — ANC headquarters are in Lusaka. So many of the South Africans who live in Canada came here as people wanting better lives. Not many are interested in politics. They don’t care too much about what’s happening in South Africa. So it’s a bit of a problem for us. The ANC in Canada has about 30 members.

Thirty?

Cecil — All over the country.

When did you meet La Guma?

Cecil — The first time I met La Guma was in Tanzania.

At Dar-es-Salaam University?

Cecil — That’s it.

In 1976?

Cecil — 1976. That’s right.

Do you know Richard Samin in Cote de Ivoire?

Cecil — Who’s that?

Richard Samin.

Cecil — Oh, Yes.

I sent the copy of the interview.

Cecil — That’s where I met La Guma. La Guma had just had a heart attack.

He had to return to London in two months?

Cecil — Yes, then I saw him many times in London and then in Cuba.

You took part in a conference at Dar-es-Salaam University?

Cecil — I was a Friendship Commonwealth visiting professor. I was sent to give lectures all over and I gave some of them in Dar-es-Salaam. And so….

He was a….

Cecil — He was a visiting writer.

A visiting writer in residence?

Cecil — In residence. So I met him then. And two years later in London I decided to write a book on La Guma, so we started talking about it. And then I started working on it, writing it. In 1982 he made me his official biographer. I’m now responsible for all his papers, for all the literary stuff. It’s my responsibility. There are some unfinshed works, which I mean to put together into a book.

Is it possible to publish `Zone of Fire’?

Cecil — It was `Zone of Fire,’ but he changed it in the end to `Crowns of Battle’.

Is it possible to publish it?

Cecil — It’s not finished, we have about three chapters. So I’m putting it together with some commentary. But it’s not ready.

I’m looking forward to the publication.

Cecil — It’s quite good, the work he didn’t on it. He was also finished a biography of his father, which I’d like to get published. And then he has a few short stories which have not been published, which we’d like to publish. He wrote some radio plays when he was living in London, as part-time work, for the BBC. Mostly detective stories. I’m going to put them all together, some can have a complete production of them. So over a period, we’ll have quite a lot of La Guma’s matherial coming out. But I’m also doing it for the South African people, so that they have a record of what La Guma was like. And Mrs. La Guma wants a good record, so she’s very anxious that I get it all done.

Why did La Guma choose to go to Cuba?

Cecil — Oh, he was quite active still with the African National Congress and they need a representative there and so they asked him. He was stationed in Cuba but he was chief executive for Cuba and the Caribbean. They often travelled to Jamaica, Trinidad, and so on. The ANC asked him to go. He liked Cuba very much. They liked him a lot. When he died, there was a service, Fidel Castro’s brother was the main speaker.

Castro?

Cecil — Castro’s brother. He spoke at the funeral. And the secretary-general of the ANC was there. He got a very big send-off, The Cubans are going to have a special second memorial service in October for La Guma. They’ve invited his wife to come, but she doesn’t think she’ll go. She has too many memories and feels too much. So maybe one of the children go, One of the children.

He had two sons, Bartholomew….

Cecil — Eugene.

Where is….

Cecil — Eugene lives in Moscow. He is married to a Russian girl. He has two children.

Two children?

Cecil — And Bartho is living in Africa, in Zambia.

Zambia, now?

Cecil — He is working for the ANC’s film unit now. He studied film and now he’s working for The ANC’s film unit. One of the other speakers who’s coming to the next conference next August, Dennis Brutus will come, too. Dennis knew Alex La Guma in South Africa. They worked together.

Dennis Brutus?

Cecil — Dennis is now in Pittsburgh. He used to be in Chicago, but he moved. And he’s now chairman of the black community vocation department at the University of Pittsburgh.

Pittsburgh. He once lived in Austin, Texas?

Cecil — He was there for one year. He was a visiting professor for one year.

Texas University published many African books?

Cecil — Well, they have a journal there, Research in African Literature and there’s a good library where they buy the original papers of many African writers. So the library is very good. there’s a good African studies (department).

And North Western University?

Cecil — North Western is very good. North Western has a good library, also. Dennis used to be at North Western. And Mphahlele was there also. So was Ngugi wa Thiong’o at North Western. There have been many Africans at North Western.

How old is Dennis?

Cecil — Dennis is one year older than La Guma. He was born in 1924.

3-A

The problem of passing?

Cecil — Yes, much like the Deep South. Yon see, passing. So we’ve had this problem, too. It means you get better jobs, better living conditions and so on and so on. Some people do that. Alex, of course, would argue against it, saying that you should think of your dignity and you should be proud that you are who you are. You don’t go trying to be someone else. What he tried to do, he was probably the first to write among the mixed race community, to try to give a picture of his community, because until then there was no picture. There was a book written on the mixed race community by a white woman. It was called God’s Step Children.

Cecil — No mixed race person has come out to talk about his community, and Alex’s columns in the newspaper New Age, and also his stories and novels then tried to give a picture of the history of these people.

Was New Age banned?.

Cecil — Yes, in 1962.

Cecil — So Alex tried, in fact, to set himself up to tell the story of the coloured people, because he felt they’d been ignored. They had been neglected. He also hoped that he could inspire in them a confidence, a pride that they were worth something, they were not nothing, they had something to offer and so his stories, if you look at them, are quite affectionate, I mean, they’re problems but he is very kind, because it is his own people. He feels for them like a father who looks at his children even though he is cross with them, he still says, “Well, that’s my children." But he still tries to be kind. So you notice that in his books he sees himself doing the job of a historian, collecting the history, a teacher showing his people what to do. And then, of course, Alex was very much a kind of an optimist, a very optimistic attitude, even though life was rough for him sometimes, all the arrests, detentions, house arrests. He always saw the bright side. lie always saw on the side of the mountain, it will be better. And so with this optimistic spirit then, when people did something wrong, he could still forgive them. For example in In the Fog of the Season’s End, you have Buekes who loved dancing. So he was unlike Richard Wright in that way. Richard Wright was very angry, and there’s a lot of bitter denunciation.

Cecil — But Richard Wright in a way went to Paris then and wrote books about his life in America. And he got out all his anger, and his bitterness. He never wanted to go back to the States. You know because he was so cross with the state of the black man in the States, you see. In a way he becomes like James Baldwin who also was very angry at what had happened. But Alex La Guma was not like that. Alex La Guma, what saved him was that he was also involved with the political movement, a liberation movement. When you work for liberation movement, and you’re also an artist you know that in your liberation philosophy there’s the strong belief that we gonna win this fight, we just got to keep going at it. We are writing what we are doing, our cause is just. And if we do it together collectively, we are going to win someday. But if you don’t do it collectively, if you don’t have a political movement, if you do it as an individual, then you’re more likely to get angry all the time, because you’ve nowhere to turn, there’s no communities to fall back on. So Alex could keep on believing, because there wasn’t just the writing going on but there was the practical political work, you see.

Yes, yes.

Cecil — He could go from one to the other. Many writers can’t because they are entirely writers and they remove themselves from the world, and so the problem is inside heads and finally in their emotions and then they destroy themselves.

If you’re also involved in your community and your world, then you don’t have the time to get only angry with yourself and destroy yourself, because you must give the energy to others. Now I think this helped. Alex was first politically involved before he became a writer, which helped a lot, because if he was at first a writer and then a politician, he would have had problems. He was first involved in politics. He then very easily went over to writing artistical. And that was because he had a gift, a talent to write, he could tell a story in a way where even though he was politically involved, he never tried to indoctrinate you. He just told a story. You ought to read, to look at the stories…. And also if you notice in Alex La Guma’s writings, he does not tell you how to think. He leaves the story there, he lets you decide what to do with it. He doesn’t say to you, “This is love. This is life." He says “Here’s a story, you deal with it." Even the story, “Coffee for the Road" you watch — when the lady explodes in the cafe. Alex La Guma didn’t tell you she is exploding because they are treating her in such an unjust way. He just says that she exploded because the situation was not human, not dignified. But you, as a reader, you have not been given any propaganda. You’ve been given a story and you can easily see, look, if I were in the same situation, I would have acted in exactly the same way. You’re looking for a cup of coffee and they tell you you can’t come inside the cafeteria, you have to go behind and, order your coffee from there, then obviously, you know, you’re going to react to it. So I think in that sense Alex tells the story but leaves it to us who are reading the story. If you read a lot of South Africa writing whether it’s novels or poetry or so on, you’ll see that there’s a lot of straight sloganeering, a lot of straight propaganda. You know you can read it and you can say, “Well, I suppose if this had been a political leaflet, it would be better but as a story. It’s not coming out, you know." He didn’t do that. That’s his story. You can see the loss of people’s rights. It is his artistic ability to take a very dry political situation, and make it live for you who are not living in South Africa, after you’ve read a story like, let’s say, `Lemon Orchard’ or “Coffee for the Road" or, let’s say, A Walk in the Night, or A Threefold Cord, you finish reading it, though you’ve never been to South Africa, it’s so graphic and it clearly describes.

4-A

Cecil — Richard Wright was also, in a way, American racism is much worse than South African racism because American racism, even though the American Constitution is against it, in practice it carries on. And in the South, the law courts always favour racists, so you could kill a black person and you have a jury that’s all on your side, and they acquit you. In South Africa, you know that there is no chance that you could ever win a law case, I mean, you don’t worry about it. Because you know there’s no chance. I believe in America, the blacks believe in the Constitution which doesn’t do anything for them. I always find it difficult. Wherever I go to the US, to the conferences and I see a lot of black Americans, scholars, lecturers, or students. I always ask them, you know, you are getting such a hard time in this country. You feel sorry for us in South Africa, but in a way we should feel sorry for you, because you are even worse off here than we are. In our country, at least we know what they are doing to us. You are having these things done, and you don’t know how to react to them….

Cecil — Alex didn’t do too well financially, you know. His family was always close, just making enough to survive. }[is wife always sold hi s. stories. She said that there were sometimes days when they had no food in the house and the children were still small and she just didn’t know where to get a piece of bread in London…. Unfortunately at this time the ANC had no way of compensating Alex with money…. That was one of the reasons why he went to Cuba because they thought it’d give him something, you know, he’d get enough to live on. The Cuban Government paid for the housing, the food,….

The Cuban Government?

Cecil — Yes, Cuban Government sees the ANC as the legitimate representative of the South African people, so they treat the South African representative as a diplomat.

In Cuba?

Cecil — Yes, in Cuba. They gave him a house in the deplomatic area. So they provided them wtih the house free and gave them a voucher to get food from special stores, gave them a car and so on. So that was the first time, from ’79 to ’85.

You visited Cuba?

Cecil —Yes, I’ve been there twice.

4-B

Cecil — I’m very concerned that there is a history of South African writers written, and prepared so that when the day of change comes, we have all this material available for our people, for our younger people to read. And all these writers who lived outside the country and who have done a lot will maybe provide them whenever they come because these children have never seen them, never heard of them. So in a way I’m trying to do a job, also for the country, to leave behind for the country and for the world, so there is a history they can go to. I think it’s very important, because just writing books for books’ sake, I think it’s a waste of time.

Cecil — Now the young people today they don’t drink, because they say it is drink that only people don’t know how to fight. So they don’t like drinking. When they start demonstrating, they call them shebeens, they beat up the people, they throw out the liquor, they chase them off. So you know they don’t only attack the government, they also go for their own people because they say all those things are not healthy and also, you know, when they get their salary, they go straight to the shebeen, they don’t go home. By the time they got home, there’s no money for the wife and children, for food, for milk, for bread, for clothes, for books…. But now many South Africans in exile, especially in England because many of those, who were political in South Africa, go to England -they get together and they drink. And when I visit them in England, I’m surprised how much they can drink….Ohh!

The younger people are hopeful!

Cecil — Yes, and they don’t drink.

The generation of 1976.

Cecil — “Soweto."

Cecil — Since 1976 they are all very militant. And they don’t drink, don’t smoke. They are very serious. The older generation, Alex La Guma’s generation, they were very good but they liked to have a nice time, you know, they liked to laugh, smoke, drink. Alex used to drink and smoke too much. We told him many times. One evening he and Elsie Nitess who was the editor of Sechaba, another South African, he lives in England, La Guma, who had been drinking most of the night…. Next morning he had to go on a plane with his student to some meeting. Well, on the plane he had a heart attack and died. He was dead when they landed. He was in his twenties. It was because of all the liquor. So we told Alex at that time, you know. At that time ANC sent him to Cuba because they knew it would be dangerous. He drank too much in London. But once he got to go to Cuba, he changed. His health was better, when I saw him in June 1985, it was very good.

He visited Moscow.

Cecil — He looked very healthy. In fact, I said to him, “Oh, you’re getting younger!" He was supposed to come to Canada in October. We were at a conference and then he wanted to make a tour of Canada. And I just was in touch with them a week before he died, to finish the arrangement. I was so shocked because I’d already sent tickets and everything. I was quite surprised because we didn’t expect it. So drink, for South Africans, it’s nothing good.

6-A

How about the younger people?

Cecil — I think the younger people will change. They’re very different because they respect each other more as human beings not as woman and man but as humans. And I think they will bring a complete change. I think what is happening in South Africa is very positive because the young people are not doing the things their fathers used to do. They have very different attitudes. And I think that’s very good for South Africa.because I’m always arguing with the ANC that we don’t just need a change of government, we need a change of humanity. In other words I feel still today that in the top leadership of the ANC there’re not enough women, and there are many, many women who work for the ANC. And but they are not getting to a high position. So I always argue that women should be treated fairly, because, you see, the majority of the members of the ANC, of course, are black, and they come from various communities, Zulu, Xhoxa, and so on. In our traditions, in African traditions, the men are brought up to be selfish. There is no sharing. The man is the boss. And the women must do all the dirty works, you know. So, in that way, many of the men who are in the ANC, especially the older men, like the generation of Oliver Tambo, the generation of Nelson Mandela -the oldest generation. They grew up being chauvinists. It takes a while for them to understand that revolution is more than just politics. It’s also your way of life. It’s what you do at home, it’s the way you treat your children, it’s the way you treat your wife. It’s a way of life. You can’t just say I’m gonna non-sexist. Because to be truly democratic. All the societes of the West talk about democracy, but it is not a democracy, it is the monopoly of the rich. They own the country, they are the power. The other people are mostly workers, who accept what is given to them. Actually the rich are taking the largest share and leaving a little bit for the bottom. And some of us are foolish enough to think we’re getting our share. It’s not true. So La Guma said the same thing in his work.

Cecil — And so the younger generation said, “No! We’re tired of talking! If we’re gonna get a change in this country, we’ll have to fight for it. But unfortunately they were not many. They were not enough people who shared that view, because most people were worried about their lives, didn’t want to die, or go to jail, and so on. The younger generation from 1976 is very different. They don’t spend as much time talking. In their minds they know what they want. They want FREEDOM NOW! EQUALITY NOW! They don’t want to wait for the next generation. They want it NOW! This is why they’re doing things we never dreamed to do. We believed in peaceful demonstration like Buekes. We went on the street all the time, with leaflets. So we got beaten up and put in jail. We didn’t do anything. We’d just given out leaflets. And then on top of that you got beaten up so badly by the police, you got tortured…. But today’s generation don’t. They don’t believe merely a change of government, they believe in the change of life. That South Africa must not concentrate so much on material things. We must concentrate on the spiritual life, improving our way of thinking about life. So, for example, the ANC says we believe in the nationalization of major industries, particularly government’s place like railways, banks, agriculture and so forth. These young people are not talking about nationalizing. They say that they believe in a socialist state where everything produced in a country is to be shared fairly among everyone. The ANC, for example, has had meetings, our leadership has had meetings with South African businessmen. I think it was in Senegal. They had several meetings at Lusaka, so the white businessmen who had come from South Africa wanted big corporations, and so they talked, and the ANC said: well you know, they asked the ANC if you formed the government, would you make the country a socialist state? Will there be no capitalism any more ? Another thing must be tried as well. We will always allow some individual enterprise, but you see, our young people in South Africa are saying No! There will be no capitalism. We are after a country that will be centrally governed and see all the wealth distributed fairly among all people. So that’s very different from what the ANC is saying. So I am always arguing that because we’ve been away from South Africa so long, we sometimes don’t understand the changes that are going on. We don’t understand the thinking of our young people. That they don’t exactly share our beliefs, basically. Our view is that, well, we could all live together, white, black, brown can all live together peacefully. It is true, we can all live together peacefully. But the point is, when the changeover takes place the whites will be in the strongest position-they will run the mining, they will run the businesses, they will have the beautiful houses, they will .live on the best areas, they will have the best schools. How are we going to change that? The ANC says that, ーWell, it will take time. But you know in Zimbabwe they are trying this and there’s a lot of people getting upset because they want to see some movement. So the ANC again are discovering that the younger people at home are saying, ー We want a decent living now. We’re not waiting for time." So again there’s going to be some trouble, because there’s going to be a need to understand the position of the younger people is not exactly the position of the ANC today. The ANC must also change, because we need to think more actively about how we can also meet the aspirations of the younger people. My own feeling is with the younger people, because they have a better vision of where we’re going and what South Africa must be….

8-A

Cecil — I went to a conference once, in Malta, and I went to hear a paper by a German scholar, a young German. He came from the University of Kiel. He talked about Ngugi on Petals of Blood. The book had just come out. So he started off his lecture by saying, “I was going on a trip. I was at the airport in Germany. I was looking for something to be read on the plane. So I went into a bookstore and saw a book with this Blood, this flower of blood and I felt, “I think I’ll read this. It must be a horrible story, full of shooting and whatnot," and I think he said he was a Marxist. So I wanted to show he doesn’t know anything about Marxist. So he gave a very superficial paper and when he finished, I was very cross, and I went up to him and asked him where he got the stupidity from to come and read this paper. And the audience all agreed with me….he then admitted he didn’t know anything about this writer,…but then you see you get that kind of thing, people don’t do their homework…but they’re so interested in getting their names in magazines and books. Most people don’t know what they’re talking about, so they read the books and say, 'Oh, no problem!’ So I felt this kind of work must be done by people who know, who care, who have a feeling for this writing. So I felt with Alex La Guma there was mostly a feeling of services, someone’s got to do it, otherwise we’re going tho have his writing messed up by a lot of people. There are many writers who need this kind of attention

執筆年

1987年

収録・公開

August 29-31, 1987, St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada