概要

アレックス・ラ・グーマの第二作 And A Threefold Cord (イギリスクリップタウン社一九八八年刊)の編註書で、大学の教科書として使いました。初版は西ドイツベルリンセブンシィーズ社で一九六四年に出版されています。

クリップタウン社刊

And a Threefold Cord(1991年、表紙絵小島けい画)

1992年に家族でジンバブエの首都ハラレにいたときに、本が届きました。表紙絵は、奥さんに描いてもらいました。衛星放送で見たナミビア辺りの映像からイメージをもらい、自分の理想の犬を放して、水彩で描いてくれました。

本文

①献辞とエピグラフ、②編註書の前書きとして書いた「アレックス・ラ・グーマとA THREEFOLD CORD」、③ブライアン・バンティングの「序」、④その日本語訳を掲載します。

①献辞とエピグラフ

This is for Blanche with Love

Two are better than one; because they have a good reward for their labour.

For if they fall, the one will lift up his fellow: but woe to him that is alone when he falleth; for he hath not another to help him up.

Again, if two lie together, then they have: heat, but how can one be warm alone?

And if one prevail against him, two shall withstand him; and a threefold cord is not quickly broken.

ECCLESIASTES IV: 9 – 12

②「アレックス・ラ・グーマとA THREEFOLD CORD」

アレックス・ラ・グーマは1925年2月20日,ケープタウンのカラード居住地区第6区で生まれました.父親ジミーが解放運動の草分けの一人でしたから,ラ・グーマは早くから政治意識に目覚め,ハイスクールを中退したあと,46年にはストライキを先導して会社を解雇されています。48年には共産党に入党し,55年には南アフリカ・カラード人民機構の議長に選ばれています。同じ年にケープカラード社会での人望と文才を認められて,反政府路線の週刊紙「ニュー・エイジ」に記者として採用されました。57年からコラム「わが街の奥で」を書き始め,62年に破壊活動法によって記者活動を断念させられるまで健筆を揮いました、

56年に他155名とともに反逆罪の嫌疑で逮捕されて以来,60年,61年,63年,66年にも逮捕・拘禁されていますが,それはラ・グーマが白人政府に脅威を与える存在だったからです。66年に釈放され,5年間の自宅拘禁を強いられたラ・グーマは,家族と共にロンドン亡命の道を選び,祖国を離れます。

亡命してからのラ・グーマは,積極的に反アパルトヘイト運動を推進します。70年にはアフリカ民族会議(ANC)ロンドン地区譜長に,78年にはカリブ代表としてキューバに赴任しました。キューバでは,南アフリカからの留学生の世話をして後進を育てたり,多くの作家会議に出席して様々な国の作家と連帯しながら精力的な創作活動をも展開します。70年にアジア・アフリカ作家会議69年度ロータス賞を授与され,79年には同作家会議議長に選出されています。81年には来日し,アジア・アフリカ・ラテンアメリカ文化会議などに出席して講演したりしています。

67年の小説『石の国』に続いて,編集評論集『アパルトヘイト』(1971),小説『季節の終わりの霧の中で』(1972),紀行文『ソビエト紀行』(1978),小説『百舌鳥のきたる時』(1979)と,単行本も次々に出版されました。しかし,ラ・グーマは,85年11月11日夕刻,心臓発作のために,キューバの首都ハバナで二度と還らぬ人となりました。60歳の若さでした。

南アフリカに最初に来たヨーロッパ人はオランダ人ですが,植民地支配を確立したのはイギリス人です。インドヘの中継地にしか過ぎなかった南アフリカの存在は,十九世紀後半にダイヤモンドと金が発見されてから急変します。オランダ人とイギリス人はその利権をめぐって争いますが,双方とも深手を負い,このままでは多数派のアフリカ人にやられるという危機感の中で,アフリカ人搾取という点に利害の一致点を見つけ出し,南アフリカ連邦(`The Union of South Africa’)をつくります。「イギリス国王に承認された」ヨーロッパからの移住者の国ということにはなっていましたが,白人がアフリカから土地を奪って作り上げた植民地に他なりません。植民地経済に組み込まれたアフリカ人の安価な労働力を基盤に,南アフリカは第一次,第二次世界大戦をへて工業国になっていきました。

1948年には,社会の底辺に沈む危機感を感じていた大半のアフリカーナーの支持を得て,国民党が政権を取り,アパルトヘイト政策を前面に掲げて反体制勢力を弾圧し始めます。

第二次大戦で殺し合った白人社会の力が低下したとき,今まで権利を主張しても聞き入れてもらえなかった黒人社会が,声を上げ始めます。アメリカでは公民権運動が激しく展開され,1956年のエジプトの共和国宣言,1957年のガーナの独立などアフリカ大陸でも解放運動は勢いを増していきました。

南アフリカでも,諸外国の動きに励まされて,1955年にクリップタウンで国民会議が開かれ,国の指針として自由憲章が採択されました。政府は反逆罪の名で指導者を弾圧しますが、解放闘争は激しくなっていきます。1960年のシャープヴィルの虐殺で,国際社会の非難を浴びますが,弾圧を強化して一歩も譲りませんでした。政府の強硬な態度に対抗して,黒人を主導する解放闘争組織ANCは,それまでの非暴力の戦略を捨てて,武力闘争を始めます。

ラ・グーマも,そんな闘いのなかで自分自身を精一杯に生きていたのです。

そして,『まして束ねし縄なれば』(And A Threefold Cord)が生まれました。

ラ・グーマが『まして束ねし縄なれば』を書いたのは,歴史を記録して,後の世の人に伝えたかったからです。そのために,南アフリカの人々の日常を語りました。1962年に,運よくナイジェリアで出版された『夜の彷徨』(A Walk in the Night)では,ケープタウンのカラード居住地区第6区の夜をさまよいながら,無為な時を過ごす若者たちを描きだしています。(1988年に,門土社からテキストが出ています。従って,本書はその続編になります)

本書では,舞台をラ・グーマは第6区からケープタウン郊外のスラムに移しています。心やさしいチャーリーを軸に,家族や恋人や親戚との日常の出来事・・・・・・葬式や出産や警察の手入れなど・・・・・・や,孤独な生き方しか出来ない寂しい人々などを織りまぜながら,アパルトヘイト体制の中で呻吟しながらも,力を合わせながらなんとか生き永らえている人々について書きました。助け合って生きる人々の姿が,ラ・グーマの目には,エピグラフの「二人は一人にまさる。其はその骨おりのために・・・・・・人もしその一人を攻め撃たば,二人してこれにあたるべし,まして東ねし縄なれば、たやすくは切れざるなり」という文章に重なったのでしょう。

ラ・グーマは世界の人々に南アフリカの実際の姿を知って欲しいとも考えて本書を書きました。作品中の多くの出来事を雨と絡ませたのは,美しい南アフリカを強調する政府の観光宜伝とは裏腹に,スラムの住人が現実に雨風に苦しんでいる姿を知って欲しかったからです。色彩語,擬声語などを駆使して,ケープの冬を「一連の絵画的,散文的銅版画」(バンティングの序)で見事に捕えています。

本書は,1988年にイギリスのクリップ・タウン社(Klip Town Books)から新たに出版された版に基づいています。初版は,ラ・グーマが未だ南アフリカにいた1964年に,東ベルリンのセブン・シィーズ社(Seven Seas Books)から出版されました。旧版にも、同僚ブライアン・バンティング(Brian Bunting)の序がついています。

作品理解の一助にと,巻末にラ・グーマ略年譜・著訳一覧・地図・南アフリカ小史を付けました。なお,ラ・グーマの人と作品については,カナダに亡命中の南アフリカ人セスゥル・エイブラハムズ(Cecil Abrahams)氏のAlex La Guma(Twayne Publishers, Boston, 1985)をお勧めしたいとおもいます。また,門土社の翻訳『まして束ねし縄なれば』(And A Threefold Cord)や著訳一覧の中で紹介しているアジア・アフリカ総合誌「ゴンドワナ」(ゴンドワナ協会発行)に寄せた私の作家・作品論も併せてお読み下されば光栄です。

1950年代のケープタウン郊外のスラムのことで,辞書では解決のつかない箇所もたくさんありましたが,ヨハネスブルグ生まれで,1980年代の初めにケープタウンに住んだ経験もある都城市在住のコンスタンス・ヒダカ(Constance Hidaka)さんに,色々とお話を伺いながら註をつけました。私たちの国南アフリカのことですからと,多くの時間を割いて下さいました。今はイギリスにいる友人のジョン(John Bi1ligsley)にも色々とお世話になりました。また、佐々木孝臣さん,宮下和子さん,奥村修一さん,南太一郎さんにも資料のお願いをしました。深くお礼申し上げます。

1991年4月宮崎にて

玉田吉行

③ブライアン・バンティングの「序」

PREFACE

It is difficult to propound the notion of `art for art’s sake’ in South Africa. Life presents problems with an insistence that cannot be ignored, and there can be few countries in the world where people are more deeply preoccupied with matters falling generally under the heading of `political’. The doctrine of apartheid, even though today foresworn by its progenitors for reasons of expediency, permeates every sphere of life, and whether you be member of parliament (White, Coloured or Indian chamber), businessman, worker, priest, sportsman or artist you cannot escape its consequences. If art is to have any significance at all, it must reflect something of this national obsession, this passion which consumes and sometimes corrodes the soul of the South African people.

Some writers, caught in the cross-currents of fierce political controversy, appalled by the intensity of coflict, or simply fearful, have, it is true, lapsed into silence rather than commit themselves to making of a judgement. But on the whole the young South African literature has shown an intense awareness of the political situation, and the most successful and profound literature has been produced by those who have loved life and truth well enough not to shrink from the facts.

It is not easy for all South Africans, however well intentioned, to know the facts. Population registration and residential segregation are so entrenched, divisions between Black and White so sharp, points of contact so few, that real intimacy is rare and surrounded by legal obstacles. Whites writing about the lives of Blacks must often rely on intuition and guesswork rather than experience; this has sometimes led to superficiality of treatment and a falsification no less regrettable because unwanted or unintentional.

The work of South Africa’s Black writers has done a great deal to correct the perspective, though they themselves have found it no easier than their White colleagues to present a fully rounded picture of the South African scene. But the Black writer has possessed one great advantage, and that is detailed and personal knowledge of the conditions and situations which cotribute to the making of the South African tragedy for the great majority of the population. While the White writer, belonging to a community which is protected and cushioned by law, custom and comparative ease of life,observes the South African struggle from afar, somewhat in the positionof a war correspondent describing the course of a conflict in which he or she is not directly involved, the Black writers as a participant on the field of battle itself. It is in the lives of the Black people that the South African drama is played out with the greatest intensity. Their joy and sorrow, happiness and hardship are experienced with a depth of feeling and in a context which is beyond the range of experience of most Whites.

The work of Alex La Guma, born and bred in Cape Town’s District Six, the heartland of a vibrant community now bullozed into history, vividly illustrates its origins. Born in 1925, Alex was the son of Jimmy La Guma, one of the pioneers of the South Afriican liberation movement who in his day had played a prominent part in the affairs of the Indus-trial and Commercial Workers’ Union (ICU), the African National Congress and the Communist Party, of whose Central Committee he was a member before its dissolution in 1950. Politics was the stuff of Alex’s life from the year of his birth right up to his death in Havana in 1985.

After completing his education at Trafalgar High School and Cape Technical College, Alex worked as a clerk, bookkeeper and factory-hand before entering the service of the liberation movement full-time. As a young man he joined the Communist Party and was a member of the Cape Town District Committee of the Party until it was banned. He maintained his political activity in the succeeding years, taking a foremost part in the preparations for the historic 1955 Congress of the People where the Freedom Charter was adopted, setting out the perspectives of the Congress Alliance headed by the African National Congress.

The 1950s witnessed a sustained assault on the Coloured community by the Nationalist regime – it sought to eliminate Coloured franchise rights and impose segregation in alll spheres of life under the provisions of the Population Registration and Group Areas Acts. Thousands of men and women were rounded up and subjected to sordid classification procedures. One woman described her ordeal at the hands of a reclassification officer in the Transvaal:

He looked at my profile from the right side, then from the left, then he examined my hair and he has a fine comb there which he runs through the head of some. He touched my nose and asked me what my mother’s looked like.

As vice-chairman of the South African Coloured People’s Organisation (SACPO), Alex La Guma was in the forefront of the people’s resistance to these barbarities. Later, Alex took over the position of chairman of SACPO, and in that capacity led the campaign against the introduction of apartheid on the Cape Town buses. (SACPO was later renamed the South African Coloured People’s Congress.)

Speaking at a protest meeting in the Cape Town Banqueting Hall in August 1955, he said:

If we all unite under the banner of the Congresses, we cannot lose the struggle for freedom and democracy. We have the strength of millions on our side, not only in South Africa but outside. The Freedom Charter is going to be the basis of the new South Africa and the future belongs to us.

On 5 December 1956 Alex La Guma was one of the 156 men and women who were rounded up by the police all over the country and flown by military plane to Johannesburg to stand trial on a charge of treason. The prosecutor argued that the democratic rights set forth in the Freedom Charter were of such a radical nature that the organisers must have envisaged the overthrow of the government by force and vio-lence as the only means of bringing them about. It took nearly five years of legal argument and political struggle before the charges were thrown out by the court and the accused enabled to return to their normal lives.

Life for the political activist and the rebel in South Africa, however, is never normal. One night in 1958 Alex was the target of an assassintion attempt when two bullets were fired through the window of the room in his home where he sat working at his desk. One bullet missed, the other grazed his neck. The would-be assassins were never traced, but a few days later Alex received an anonymous letter through the post reading: `Sorry we missed you. Will call again.

The patriots.’ The treason Trial was not yet over when the country was plunged into further turmoil following the police massacres at Sharpeville and Lang; on 21 March 1960 and the declaration of a State of Emergency by the Nationalist regime. Ruling by decree, the government arrested 20000 people throughout the country. Some dubbed `idlers’ and `tsotsis’ were hastily processed by kangaroo courts held secretly in the jails and pressed into forced labour in remote districts. Owr 2,000 of the top political leaders of the people were detained in prison without trial for periods of up to five months. Among them was Alex La Guma. He spent the weary months of incarceration reading and writing, preparing himself for the career in which he was later to have such success.

Alex had been a voracious reader all his life and from an early age he had tried his hand at writing. His first professional efforts, however, were as a member of the staff of the progressive newspaper New Age whose staff he joined in 1956 and whose pages he dominated with cartoons, news reports, stories and many striking vignettes of life and struggle among the population of Cape Town.

All the while he continued with his political work and was in no way discouraged by the persecution to which he was subjected. In 1959 he was arrested with Ronald Segal and Joseph Morolong for entering Nyanga township, Cape Town, without a permit and with pamphlets calling for an economic boycott of apartheid firms and institutions. In 1961, when Nelson Mandela, as spokesman of the National Action Committee of the Pietermaritzburg. All-in African Conference, called for a three-day strike at the end of May in protest against the inauguration of the Verwoerd Republic, Alex La Guma and his colleagues in the Coloured People’s Congrss threw themselves into the campaign but were arrested and held for 12 days without bail under a new law specially passed to deal with the threat posed by the strike call. Although its leaders were in jail or in hiding during the crucial period before the strike was due to start, the Coloured community responded magnificently and Cape Town industry and commerce suffered heavily during the three days of the strike.

In July 1961 Alex was banned under the Suppression of Communism Act and in September charged under the Act for organising an illegal strike, but the charges were later withdrawn. In December 1961 he was ordered by the Minister of Justice to resign from the Coloured People’s Congress. That same month, however, the people’s patience ran out and on 16 December a series of bomb explosions directed against government buildings and installations in various parts of the country heralded the appearance of Umkhonto we Sizwe, the military wing of the liberation movement.

The regime’s response was the notorious General Laws Amendment Act of 1962, the so-called Sabotage Act, providing inter alia for the placing of government opponents under house arrest. In December 1962 Alex La Guma was served with a notice confining him to his home for 24 hours a day. The only visitors permitted him for the five years of his notice were his mother, parents-in-law and a doctor and lawyer who had not been named or banned under the Suppression of Communism Act.

The fact that he was living under 24-hour house arrest, and thus completely cut off from all possibility of political action, did not save Alex La Guma from still further victimisation. Following the passing of a 90-day detention-without-trial law in 1963, Alex was one of those arrested and detained without trial. In prison he was held in solitary confinement, locked in his cell alone for 231/2 hours a day, the remaining half-hour being allowed for `exercise’ – also on his own. As was the case with the other detainees, he was denied visitors and any reading or writing material, refused access to his legal adviser and generally subjected to the most abominable forms of mental torture so that he might be forced to answer questions to the satisfaction of the police.

He did not give way, and in order to bring further pressure to bear on him, his wife Blanche, a nursing midwife, was also detained. Their two children Eugene and Bartholomew, had to be cared for by relatives. Blanche La Guma was later released, but almost immediately served with a banning order and in due course Alex was also released, but on bail, facing a charge of being in possession of banned literature. He was convicted and given a suspended sentence of three years’ imprisonment.

In 1966 Alex La Guma was detained again. By, this time the repression was so intense that on release he and Blanche were forced to leave the country with their two children. They first settled in London, where they played a large part in consolidating the ANC presence in the United Kingdom. Later they moved to Havana when Alex was appointed chief representative of ANC in Cuba. Under the supervision of Alex and Blanche hundreds of South African students were able to acquire the education in various fields which was denied them at home.

During the years of exile Alex devoted as much time as possible to his writing, and also involved himself in the affairs of the Afro-Asian Writers’ Association. He was one of the presidents of the World Peace Council. He died in hospital in Havana on 11 October 1985 after a heart attack. He was 60 years old.

At the time of his death Alex La Guma had been secretary-general of the Afro-Asian Writers’ Association for several years and in 1969 was a winner of the Association’s Lotus Prize for Literature. In honour of his sixtieth birthday in 1985 he received the Order of the Friendship of the Peoples from the USSR, the Order of Arts and Letters from France and a literary award from Congo.

It was with the publication of his novel A Walk in the Night in 1962 that Alex La Guma’s talents as a writer were first revealed to a wider audience. Because he had been banned, nothing he said or wrote could be reproduced in any way in South Africa, so his first novel was brought out by Mbari Publications in Nigeria. A few copies were smuggled into the country and passed from hand to hand. The book won instant recognition as a work of talent and imagination, was circulated world-wide and translated into several languages.

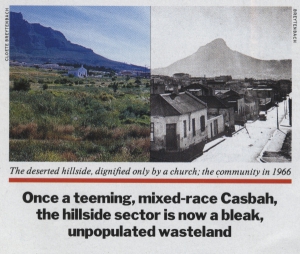

It is a short novel – barely 90 pages long. But in its pages teem the variegated types of Cape Town’s District Six – the bar flies, the louts and touts, the workers and their wives, the prostitutes and pimps, the skollies, who constituted the most colourful community in Cape Town. District Six is no more, its buildings flattened and its population dispersed in terms of the Group Areas Act, but nobody who ever passed through District Six could ever forget its winding, crowded streets, its jostling humanity, its smells, its poverty and wretchedness, its vivacity and infinite variety. For all its outward degradation, the pulse of life beat strongly in its veins – so strongly that to this day the regime’s attempts to convert it into a `White’ area have been frustrated by the resistance of the whole Cape Town community, Black and White alike. The resentment of the people of District Six against their dispossession by the racists is being echoed today in an all-out struggle by the youth of the Western Cape against the regime and its police and military forces.

Alex La Guma knew District Six intimately, having lived there, in No.2 Roger Street, for most of his early life before moving to Garlandale. He knew and understood the people and their problems, their `troubles’, as they called them, and he wrote of them with intimacy and care. These are not cardboard characters, strutting lifelessly through his pages, but real, live, flesh and blood men and women who, though weighed down by the neglect and insult of the world, yet proclaim insistently their determination to survive, to eat, drink and make love, to endure the loneliness and terror and to welcome the cleansing dawn of tomorrow.

It is the very completeness of his knowledge and understanding of his milieu that gives Alex La Guma’s prose its incisive bite. He does not strain for effect but etches his cameos of working class and lumpen life with artistry and precision. You can feel the grime on the tenement walls, smell the mounds of rubbish in the back lanes, hear the bursts of laughter from the corner bar, see the flash of the knife drawn in the heat of the quarrel. It is as dramatic and vivid as if it were taking place before your very eyes.

Part of the secret of Alex La Guma’s success is the fidelity of his dialogue to the living speech of the people. The words burst from the page with startling realism, crackling like newly-printed bank notes. He has the knack of creating a character from his speech, the language of one subtly differentiating it from another. These are real people talking – terse, racy, humorous and convincing as truth.

Nothing Alex wrote was ever able to circulate in South Africa except illegally. His name is still on the banned list. As though to make doubly sure, the censors seized copies of A Walk in the Night as they entered the country by post in January 1963, declaring they found the book `objectionable’. But the quality of Alex’s writing overcame the efforts of the censors to suppress it, and his work over the years won widespread recognition both at home and abroad. A Walk in the Night was followed in 1964 by And A Threefold Cord, this time dealing with life in one of the shanty towns sprawled on the periphery of Cape Town. Here are housed the tens of thousands of Blacks-Coloured and African-for whom there is no `official’ place to live, clutching precariously to life on the outskirts of the cities which offer their only hope of subsistence. Many of the inhabitants are in the urban area illegally, lacking the papers which establish their right to existence, a prey to perpetual police raids, insecurity and poverty. Home for them is a crazily-constructed shack providing only the barest shelter from the elements.

There are no paved streets, sanitation, drainage or electric light in these areas; water has to be bought by the capful. In the Cape winter, when rain comes pouring down, the roofs leak and the whole neighbourhood becomes sodden and waterlogged. Over all hovers the smell of dirt and wretchedness. Children play in the mud, and men and women flounder in the dark going to and from work-if they are lucky enough to have work.

And A Threefold Cord is drenched in the wet and misery of the Cape winter, whose grey and dreary tones Alex La Guma has captured in a series of graphic prose-etchings. It could have been depressing, this picture of South Africa’s lower depths, with its incidents of sordid brutality and infinite desolation. But Alex La Guma’s compassion and fidelity to life infuse it with a basic optimism. His electric dialogue flashes with the lightning of the human spirit. His message is: unity is strength – if people face the world on their own, they get destroyed; if they work together, they can survive anything.

Alex La Guma’s next novel was The Stone Country (1967), a story of bleak walls, dark corridors and clanging doors distilled from his prison experiences; followed by In the Fog of the Season’s End (1972), recounting the danger and daring of work underground, and Time of the Butcherbird (1979), dealing with people’s resistance to the threat of forced removal to a bantustan. In addition to writing many short stories,

Alex La Guma also edited Apartheid: A Collection of Writings on South African Racism by South Africans and after extensive travels in the Soviet Union, A Soviet Journey (1978) . He wrote pieces besides and was busy on a new work Crowns of Battle at the time of his death.

It was the mixture of realism and optimism which was the hallmark of Alex La Guma’s work. He faced life squarely and did not try to hide its nastiness for those at the bottom of the tip but always retained his confidence that working together, the oppressed people could transform their world, end the nightmare of capitalsm, exploitation, racism and prejudice and build a new world based on rationality and co-operation. But he was not a preacher. He was essentially a story-teller with a sharp eye for detail and a warm sense of humour There was no malice in him.

In one of the first pieces he wrote for the newspaper New Age (30 August 1956), Alex looked at the plight ofthe Coloured people in Cape Town:

There is a story told among the old people which says that one day, many years ago, God summoned White Man and Coloured Man and placed two boxes before them. One box was very big and the other small. God then turned to Coloured Man and told him to choose one of the boxes. Coloured Man immediately chose the bigger and left the other to White Man. When he opened his box, Coloured Man found a pick and shovel inside it; White Man found gold in his box.

The people have many explanation for their lot. Some of these take the form of folk tales, superstitions and myths; others are downright logical. But in all there is a common cosciousness that oppression, suffering and hardships are facts of life. And they have learned to temper hardship with humour, and to sweeten the bitter pill of their drab lives with the honey of a satirical philosophy. But they have always been aware of pain….

The census declares that we are almost one and a quarter million. But if you identify a people, not by names and the colour of their skin, but by hardship and joy, pleasure and suffering, cherished hopes and broken dreams, the grinding monotony of toil without gain, despair wand starvation, illiteracy, tuberculosis and malnutition, laughter and vice, ignorance, genius, superstition, ageless wisdom and undying confidence, love and hatred, then you will have to give up counting. People are like identical books with only different dust jackets. The title and text are the same.

And since man is only human, he must rise in the morning, throw off the blanket of night and look at the sun.

BRIAN BUNTING, 1988

④ブライアン・バンティングの「序」の日本語訳

序

南アフリカで「芸術のための芸術」という概念を持ち出すのは容易なことではありません。人生そのものが執拗に様々な問題を投げかけ、その執拗さを無視できないからです。世界中を見渡してみても、この国ほど、頭に「政治的」という言葉がつく問題に人々が深くかかわっている国も少ないでしょう。アパルトヘイト政策は、始めた人たちが政略的な理由からその政策を否定している今日でも、人生のあらゆる局面に顔を出し、(白人の、カラードの、あるいはインド人の) 国会議員であれ、実業家であれ、労働者や聖職者、あるいは運動家や芸術家であれ、その政策の必然的な結果から逃れることはできません。もし、芸術というものに意義があるとすれば、この国の人々に取りついて離れない強迫観念や、南アフリカの人々の魂を憔悴させ、時には魂を崩壊させる感情を映しだすべきです。

反対勢力の激しい政治論争に恐れをなしたり、抗争の激しさに圧倒されたり、あるいは単に恐怖心を抱いて、自分の立場を明らかにしてある判断を示すよりも沈黙を守ろうとする作家もいることは確かです。しかし、全体として、まだ歴史は浅いながらも、南アフリカ文学ははっきりと政治的な状況を意識していることを示してきました。色々な事実に怯むことなく、人生や真実を大切に思う人たちによって、最も優れた、味わい深い文学が生み出されてきたのです。

いくらそのつもりでも、南アフリカのすべての人々が様々な事実を知るのは容易なことではありません。人口登録や居住区の人種による隔離政策は厳しく、黒人と白人の間の分け隔ては非常にはっきりとしていて、両者の接点は極めて少ないのです。したがって、法的な障害があり過ぎて、現実に親しく付き合うのは極めて稀なことです。白人が黒人の生活を書こうとすれば、経験によるより、むしろ直感や当て推量に頼らざるを得ない場合が多くなります。そのために、時には人物の扱いが上すべりになっていたり、ごまかされたりしている場合もありますが、自ら望んだり意図したりしたものでないだけに、かえって残念です。

南アフリカの黒人作家は、白人の作家に劣らず、うまく洗練された形で全体の状況を描きだすのが難しいと感じながらも、作品を通して、南アフリカの全体像をただすのに大きな成果を収めてきました。黒人作家には、たえず一つだけ、白人作家よりも有利な点があったのです。つまり、南アフリカの人口の大多数を占める黒人に悲劇をもたらしている条件や状況を、詳しく、個人的に知っているという点です。白人の作家は、法律や習慣や黒人と比較すれば極めて安楽な生活によって保護され、人種の闘争からワン・クッションおかれた社会に所属しながら、どちらかと言えば、自分が直接かかわってはいない戦闘の状況を描く従軍記者に似た立場から、南アフリカの闘いを遠くから観察します。しかし、黒人作家の場合は、戦場で実際に闘っている戦士としてものを書きます。南アフリカのドラマがもっとも強烈に演じられるのは、黒人の生活の真っ只中においてです。喜びも悲しみも、嬉しさも厳しさも、その人たちの心の奥深くで感じたもので、たいていの白人の経験の枠をこえた状況のなかで体験したものです。

ブルドーザーで一掃され、今は歴史の中に消えてしまいましたが、かつては活気に満ちたカラード社会の中心地であった、ケープタウンの第六区に生まれ育ったアレックス・ラ・グーマの作品は、その街の姿を鮮明に描き出しています。アレックスは、ジミー・ラ・グーマの長男として、一九二五年に生まれました。父親ジミーは、南アフリカ闘争の草分けの一人で、当時すでに、通商産業労働者組合(ICU)、アフリカ民族会議、それに南アフリカ共産党の業務で、重要な役割を演じていました。共産党では、党が一九五〇年に解散させられるまで、中央委員会の一員でした。生まれた年から、一九八五年にハバナで死ぬ間際まで、政治は、アレックスの生命そのものだったのです。

トラファルガル・ハイスクールとケープ・テクニカル・カレッジを終えたあと、解放闘争に常時専念するようになるまで、事務員や会計係や工員として働きました。若年ながら共産党に入党し、党活動が禁止されるまで、党のケープタウン地区委員会のメンバーでした。その後も政治活動を続け、自由憲章が採択され、アフリカ民族会議の主導で会議運動が始まるきっかとなった、歴史的な一九五五年の国民会議の準備をするために、重要な役割を果たしました。

一九五〇年代には、政府の承認を受けて、国民党政権が、カラード社会に激しく襲いかかりました。体制は、人口登録法と集団地域法の条文をたてに、カラードのすべての権利を剥奪し、生活のあらゆる局面に人種隔離政策を押しつけようとしたのです。何千人もの人々が逮捕され、人種別に分類するという浅ましい作業に屈してしまいました。トランスバール州で人種別再分類の作業を担当した係官の手にかかった自らの苦い体験を、ある女性が次のように語っています。

検査官は、初めは右側から、次に左側から、私の横顔を見ました。それから、髪を念入りに調べました。目の細かい櫛をちゃんと持っていて、髪を少し摘むと、毛先のほうに櫛の目を入れたのです。そのあと、鼻に触って、おまえの母親の鼻はどんな形をしているかと聞きました。

南アフリカ・カラード人民機構(SACPO)の副議長として、アレックス・ラ・グーマは、こういった非道な行為に抵抗する最前線に立っていました。のちに、アレックスはSACPOの議長を引き継ぎ、その立場から、ケープタウンのバスにアパルトヘイト政策を導入しようとする動きに反対して、抗議運動を展開しました。(SACPOは、のちに南アフリカ・カラード人民会議と改名されました)

一九五五年八月のケープタウン会館での抗議集会で、ラ・グーマは次のように語っています。

みんなが国民会議の旗の下に団結すれば、自由と民主主義を求める闘いに敗れることはありません。南アフリカ国内だけでなく、国外にも、我々の側には、何百万という味方がついています。自由憲章が新しい南アフリカの基礎となり、未来は我々のものなのです。

一九五六年十二月五日、国じゅうで百五十六名の男女が警察に逮捕されましたが、アレックス・ラ・グーマもその中の一人でした。百五十六名は軍用機でヨハネスブルクに運ばれ、反逆罪で起訴されて裁判にかけられました。告訴側は、自由憲章で述べられた民主的な諸権利は極めて過激なものであり、国民会議を主催した人たちは、目的を達成する唯一の手段として武力と暴力によって政府の転覆をはかっていたに違いないと主張しました。この法廷論争と政治闘争については、裁判所で起訴事実が却下され、被告が自分たちの普段の生活に戻れるようになるまで、ほぼ五年の歳月が必要でした。

南アフリカで、積極的に政治活動をする人や、体制に反対して闘う人の生活は、決して正常ではありません。一九五八年のある夜、アレックスは暗殺計画の標的にされ、机に向かって仕事をしていた部屋の窓から二発の銃弾を撃ちこまれました。その一発は外れましたが、もう一発がアレックスの首をかすめました。暗殺者に見せかけた犯人の捜査は行なわれず、二、三日してからアレックスはポストに投げこまれた「おまえを殺りそこなって残念だ。またやって来る。愛国者」という匿名の手紙を受け取っています。

反逆裁判が未だ結審しないうちに、一九六〇年三月二十一日のシャープヴィルやランガでの警察による大量虐殺や、国民党政権による非常事態宣言に続いて、国じゅうがさらに激しい騒動に巻きこまれていきました。法に従って、政府は全国で二万人を逮捕しました。〈怠け者〉や〈浮浪者〉の名のもとに、急遽刑務所内で極秘裡に開かれた私的裁判にかけられて、遠隔地での強制労働につかされる者も出ました。二千人以上の政治的指導者たちが、裁判なしに、最高五か月のあいだ、刑務所に拘禁されたのです。アレックス・ラ・グーマもその中の一人でした。アレックスは、本を読んだり、ものを書いたり、のちに成功を収めることになる自らの仕事の準備をしながら、その幽閉された退屈な数か月間を過ごしたのです。

アレックスは生涯を通じて大の読書家で、かなり早い時期からものを書く腕試しをやっていました。しかしながら、仕事として本格的にやり始めるのは、一九五六年にスタッフに加わった進歩的な新聞『ニュー・エイジ』の記者としてでした。アレックスはそのペイジを、ケープタウンの人々の生活や闘争についての漫画やニュース記事、物語やたくさんの印象的な写真などで飾り立てました。

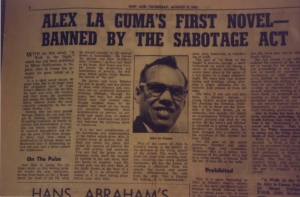

「ニュー・エイジ」一九六二年八月六日 ラ・グーマの活動禁止を報じている。カリフォルニア大学ロサンジェルス校(UCLA)所蔵

その間じゅう、アレックスは政治活動も続け、嫌な思いを強いられる迫害にも決して気落ちすることはありませんでした。一九五六年、アレックスは、アパルトヘイト政策をとる事業や公共施設への経済的なボイコットを呼びかけるパンフレットを持って、許可証なしにニャンガ黒人居住区に入ったという理由で、ロナルド・シーガル、ジョゼフ・モロロングと共に逮捕されました。一九六一年には、ピーターマリッツブルク全アフリカ人会議の全国行動委員会のスポークスマンであるネルソン・マンデラが、ファヴールトの共和国宣言の式典に抗議して五月の終わりに三日間のゼネストを呼びかけた時、アレックス・ラ・グーマとカラード人民会議の仲間は、その呼びかけに応じて抗議運動に加わりましたが、逮捕され、政府がストライキの脅しに対処するために特別に成立させた新法の下で、裁判までは保釈金も積めない状態で、十二日間拘禁されました。ストライキが始まる前の大事な時期に指導者たちが刑務所にいるか、どこかに潜んでいたにもかかわらず、カラード社会の対応はすばらしく、ストライキの行なわれた三日間、ケープタウンの会社や商店は大きな打撃を受けています。

一九六一年六月に、アレックスは共産主義弾圧法で一切の活動を禁止されました。九月には不法なストライキを組織した嫌疑により、同法で起訴されましたが、その起訴はのちに取り下げられました。一九六一年十二月には、法務大臣からカラード人民会議の議長を辞めるように命じられました。しかし、同月、人々の忍耐は限界を越え、国じゅうのあらゆる地域の政府の建物や施設に対して向けられ一連の爆破事件は、解放運動の武力闘争部門、ウムコント・ウェ・シズウェの出現の前ぶれとなりました。

政府の反応は、悪名高い一九六二年の一般法修正令、いわゆる破壊活動法 (サボタージュ・アクト) で、なかでも、反体制の人間を自宅拘禁できる条文を含んでいました。一九六二年十二月に、アレックス・ラ・グーマは、一日に二十四時間、自宅拘禁を命ず、という通告書をつきつけられました。その通告の五年間に、アレックスを訪れることができる者は、わずかに母親と、妻の両親、それに過去、共産主義弾圧法に触れたり、活動を禁止されたりした経験のない医者と弁護士だけでした。

二十四時間の自宅拘禁生活をしていたという事実、その結果政治的な活動の可能性を完全に奪われたと言う事実でさえも、アレックス・ラ・グーマがさらに犠牲を強いられるという事態を救えませんでした。一九六三年に九十日間無裁判拘禁法が議会を通過したのに続いて、アレックスも逮捕され、裁判なしに拘禁されたのです。刑務所では、一日に二十三時間半、独房に監禁され、残りの半時間が「運動」と自分の時間にあてられるという孤独拘禁の状態におかれました。他の拘禁者の場合と同じように、アレックスも来訪者や読むもの、書くものを許されないばかりではなく、法的な助言者が近づくことも拒まれ、もっとも忌まわしい形の精神的な拷問を強いられて、警察の満足がいくまで尋問に答えることを強要される可能性もあったのです。

アレックスは屈しませんでした。アレックスにさらに圧力をかけるために、政府は、看護婦と助産婦をしていた妻ブランシも逮捕しました。二人の子供ユージーンとバーソロミューは、親戚が世話しなければなりませんでした。ブランシ・ラ・グーマは、のちに釈放されましたが、ほとんど同時に活動禁止命令も言い渡されました。当然の順序としてアレックスも釈放されましたが、保釈中の身で、発禁処分の文学書を所持していたとの罪で起訴される事態に直面しました。アレックスは有罪とされ、執行猶予つき三年の実刑を言い渡されたのです。

一九六六年、アレックス・ラ・グーマは再び拘禁されました。この頃までには、弾圧は非常に厳しいものになっていましたから、アレックスとブランシは二人の子供と一緒に祖国を離れることを余儀なくされました。家族は、最初ロンドンに落ち着き、イギリスにおけるANCの存在を強固なものにするために、大きな役目を果たしました。のちにアレックスがキューバでのANC主代表に指名されたとき、家族はハバナに移り住みました。アレックスとブランシの監督のもとに、何百人もの南アフリカの学生が、祖国では拒否された様々な分野の教育を受けることができました。

亡命の期間中、アレックスはできるだけ多くの時間を書くことに専念し、自らアジア・アフリカ作家会議の仕事にもかかわりました。アレックスは、世界平和評議会の議長の一人でもありました。一九八五年十月十一日、アレックスは、心臓発作のため、ハバナの病院で亡くなりました。六十歳でした。

死ぬ時までの数年間、アレックス・ラ・グーマはアジア・アフリカ作家会議の事務総長を務め、一九六九年にはその作家会議のロータス文学賞の受賞者になりました。一九八五年には、六十歳の誕生日を記念して、ソビエト連邦から民族友好勲章を、フランスからは文芸勲章を、コンゴからは文学賞を受けました。

アレックス・ラ・グーマが作家として、より広範な読者にその才能を最初にあらわしたのは、一九六二年の小説『夜の彷徨』の出版と同時でした。アレックスはすでに活動を禁じられ、喋ったり書いたりしたものは国内ではいかなる手段でも再現されることはありませんでしたから、最初の小説はナイジェリアのムバリ出版社から出版されました。二、三冊の本が密かに国内に持ちこまれ、人の手を経て読み継がれました。その本はただちに、想像力に富んだ優れた作品としての評価を得て世界中に出まわり、数力国語に翻訳されました。

その本は、わずか九十ペイジの長さの短篇小説です。しかし、そのペイジとペイジの間には、ケープタウンで最も色鮮やかな社会を構成した、カフェの常連や田舎者や客引き、労働者の夫婦、商売女やポン引きにちんぴらなど、ケープタウン第六区のさまざまなタイプの人物が登場するのです。建物がなぎ倒され、そこに住んでいた人たちが集団地域法によって四散させられて、第六区はすでにありませんが、かつて第六区を通ったことがある者は、その曲がりくねった混雑する通りを、その人間味あふれる騒がしさを、その臭いを、その貧しさと惨めさを、そして活発さと限りない多様性を忘れることはできないでしょう。いくら見た目が悪くても、その静脈の中には生命の鼓動が激しく鳴り響いていたのです。その鼓動があまりにも激しいので、今日まで度々その地区を「白人」地区に変えようと政府が努力してきましたが、黒人白人を問わず、ケープタウン社会全体の抵抗にあって、その計画は失敗に終わっています。人種差別をする人たちに土地を奪われたことに対する第六区の人々の憤りは、今日、ケープ西部の若者による政権と政策と軍隊に反対する全面的な闘争の中にこだましています。

1966年に強制立ち退きにあったケープタウン第六区の今と昔(タイム誌)

アレックス・ラ・グーマは第六区をよく知っていました。ロジャー通り二番に住み、のちにガーランディルに移り住むまで、幼い頃の大半をそこで過ごしたからです。アレックスは、そこに住む人たちと、その人たちが「トラブル」と呼んでいたその人たちの問題を理解し、よく知っていて、心をこめ、細心の注意を払ってその問題について書きました。そこに登場する人物は、ペイジとペイジの間を生気なく気取って歩くような非現実的なものではなく、リアルで生き生きとした血肉の通った男性であり、女性なのです。その人たちは、世の中に無視され、軽蔑されて気落ちしてはいますが、生き延びて、食べたり飲んだり愛し合ったり、あるいは寂しさや恐怖に耐え、汚れを洗い流してくれる明日の夜明けを迎える自分たちの意志の固さを、執拗に物語っているのです。

アレックス・ラ・グーマの散文が鋭く訴えるのは、自分の環境をよく知り、完全に理解していたからです。効果をねらって努力するのではなく、芸術的な手腕と正確さで、労働者階級と権利を奪われた生活を浮き彫りにしています。住まいの壁にこびりついた汚れを感じ、裏通りのごみの山の臭いを嗅ぎ、街角のバーからどっと聞こえてくる笑い声を聞き、喧嘩の真っ最中に抜かれたナイフのきらっと輝く光を見ることができます。すべて、実際に目の前で起こっているかのように、劇的で、鮮明なのです。

アレックス・ラ・グーマが成功した秘訣は、物語の中の会話が人々が実際に話している会話に忠実であったことにもよっています。新しく刷り上がった紙幣のようにぱりっと音を立てながら、こちらをどきっとさせるような現実味を帯びて、人々の言葉が物語のペイジからあふれてきます。アレックスは、登場人物の言葉を次々と微妙に変化させながら、自分の語り口から物語の人物を創り出すこつを心得ています。それらの話は、真実のように、きびきびとして元気よく、ユーモラスで説得力のある、現に生きている人々の話なのです。

アレックスの書いたものは、法律に違反することなく、南アフリカで一般に読まれる可能性はありません。アレックスの名前は、活動を禁止された人のリストにまだ記載されています。重ねて念を押すかのように、一九六三年一月に郵便で『夜の彷徨』が国内に送られてきたとき、検閲官はその書が反政府的であると認定する、と宣告して、何冊もの『夜の彷徨』を押収しました。しかし、アレックスの書いたものは、それを押さえこもうとする検閲官の活動にもうち勝ち、その作品は長年にわたって、国内外の広範な評価を得てきました。『夜の彷徨』に続いて、一九六四年には『まして束ねし縄なれば』が出版されました。今回は、ケープタウン周辺に広がるスラムの生活を取り扱ったものでした。そこには、何万人という黒人 (カラードとアフリカ人) が小屋を立てて雨風を凌いでいます。その人たちは、「公式に認められた」住むための場所を持たず、生き延びる唯一の希望を自分たちに提供してくれる都市の周辺での不安定な生活にしがみついているのです。その住民の多くは存在する権利を保障してくれる書類もなく、度重なる警察の手入れや不安や貧乏の餌食となりながら、不法に都市地域に滞在しています。その人たちの家は、とにかく何とか雨露だけでも凌げるようにとあらゆる材料を使って立てられた粗末な小屋なのです。

それらの地域には、舗装された道路も、下水も、排水施設や電灯もありません。水も、バケツなどを運んで買いに行かなければならないのです。雨が激しく降りつけるケープの冬には、屋根は雨漏りがして、その辺りは一帯に水浸しとなり、地面はじゅくじゅくの状態です。どこに行っても、泥と惨めさの臭いが漂います。子供たちは泥の中で遊び、大人たちは泥に足を取られながら、暗闇の中を仕事に通うのです、それも、運よく仕事にありつけばの話なのですが・・・・・・。

『まして束ねし縄なれば』は全篇にケープの冬の湿気と惨めさが充満し、その灰色の侘びしい色調を一連の絵画的、散文的銅板画で捉えています。この作品は忌まわしいほど残虐な、限りなく絶望的な数々の出来事で南アフリカの奥深くを描きだしているので、あるいは読者の気を滅入らせたこともあったでしょう。しかし、物語の根底には、アレックス・ラ・グーマの人生に対する情熱と誠実さにより、楽観的な雰囲気が漂っています。わくわくする会話は、心の機微を捉えて生き生きと輝いています。アレックスのメッセージは・・・・・・団結は力である。独りで世間に立ち向かっても打ち負かされるが、みんなで協力してやれば、何事も切り抜けられる・・・・・・というものです。

その次のアレックス・ラ・グーマの小説は『石の国』(一九七六年) で、自らの獄中体験から生み出された、寒々とした壁や暗い廊下やガチャーンと響くドアの物語です。そのあと、危険で大胆不敵な地下活動を詳しく書いた『季節の終わりの霧の中にて』(一九七二年)、バンツースタンヘの強制移住に反対して闘う人々の抵抗運動を取り扱った『百舌鳥のきたる時』(一九七九年) と続きます。数々の短篇だけでなく、『アパルトヘイト―南アフリカの人種差別に関する南アフリカ人の著作集』(一九七一年) をも編集し、広くソビエト連邦を旅行したのちに『ソビエト旅行』(一九七八年) も出版しました。他にもたくさんの小品を書き、死ぬ間際には、新作『闘いの王冠』の執筆にいそしんでいました。

Stone Country (神戸市外国語大学図書館黒人文庫所蔵)

アレックス・ラ・グーマの作品の特徴は、リアリズムと楽天性を混ぜ合わせたものでした。アレックスは人生に真っ向から立ち向かい、掃き溜めの底にいる人たちに対する不快感を隠そうとはしませんでしたが、力を合わせてやれば、虐げられた人たちが自分たちの世界を変革し、資本主義や搾取、人種差別や偏見という悪夢を終わらせ、理性と協調に基づく新しい世界が構築できるという確固たる信念をいつも持ち続けていました。しかし、説教師ではありませんでした。アレックスは、本質的に、細部にまで行き届いた鋭い目と温かいユーモアの感覚を備えた物語作家でした。アレックスに敵意はありませんでした。

『ニュー・エイジ』紙に書いた初期の作品 (一九五六年八月三十日) の中で、アレックスはケープタウンの人々の窮状を次のように見ていました。

年寄りの間で語られる次のような話があります。何年も前のある日、神さまは白人とカラードの人を召されて、二人の前に箱を二つお置きになりました。箱の一つは大変大きく、もう片方の箱は小さいものでした。そのあと、神さまはカラードの人の方を向いて、箱をどちらか選ぶようにとおっしゃいました。カラードの人はすぐさま大きい箱を取り、もう片方を白人に残しました。箱を開けたとき、カラードの人はつるはしとシャベルを見つけました。一方、白人の方は、箱の中に金を見つけました。

人は、自分の運命を解釈する様々な説明づけを行ないます。民間説話、迷信、神話などの形を取る場合もあれば、完全に論理に適っている場合もあります。しかし、いずれの場合にも共通して、抑圧や苦しみや苦難が現実の人生であるという自覚があります。そして人々は、辛さをユーモアで和らげ、単調な生活の苦い薬を風刺的な人生哲学という蜂蜜で甘くするようになりました。しかし、人々はいつも痛みを意識しているのです・・・・・・。

国勢調査では、私たちカラードの人口はほぼ百二十五万人と言われています。しかし、身元の確認を姓名とか肌の色とかでは行なわず、厳しさと喜び、楽しさと苦しさ、憧れと挫折、報われることのない辛く単調な仕事、絶望と飢餓、文盲、肺炎と栄養失調、笑いと悪徳、無知、天才、迷信、永遠の知恵と揺るぎない自信、愛と憎しみなどで行なえば、きっと数えること自体を諦めざるを得ないでしょう。人々は、違った表紙によって初めてそれぞれの違いが区別できる本と似ています。

そして、人はしょせん神ならぬ身、人間でしかないのですから、朝起きれば、夜の毛布を投げ捨て、太陽に顔を向けなければならないのです。

一九八八年 ブライアン・バンティング

本文(写真作業中)

執筆年

1991年

収録・公開

註釈書、Mondo Books