概要

修士論文です。5年間の高校の教員生活に疲れ果て、ゆっくり眠りたい、の一心で高校に在籍したまま、教員の再養成課程にもぐりこみました。兵庫教育大学大学院学校教育研究科教科・領域教育専攻言語系コース修士課程です。覚えられないほど名前が長いのは、多分、何か引け目があるのでしょう。

入学試験を受けるのに卒業大学の教官の推薦書が必要とのことで、愛校心などとおよそ縁のない僕は、結局講義で何やらマルクスの労働と人間疎外の問題を熱く語っていたかすかな記憶を手繰り寄せ、その教師の住む奈良の自宅までおずおずと出かけました。「管理職を養成して職員を分断支配することを目論む教員再養成の大学院の新設に私は強く反対している、お前は何を考えているのか」、とその人は怒っていたような。結局、推薦書は書いてもらえませんでした。試験当日、試験会場の甲南女子大学の校門前でその人はマイクを持って大声で演説をしていました。やめて帰えろ、と引き返していたら、車が止まって甲南女子大学はどこですか?と聞かれました。ここぞとばかり乗り込んで一気に校門を突破してやろうと目論んだのですが、車は校門のところで止められ、人だかりの中に放り込まれるはめに。マイクを持った奴が、お前、その髭で教育出来るのか?放っといてくれ。

結局、こづかれて押されて気がついたら、校門の中、ま、いいや、このまま試験を受けて帰るか、それが後から振り返って見れば、大きな分岐点となりました。

マイクを持って日教組の旗振りをしていた人は、大学紛争で学生側につき反体制の姿勢を示していたようですが、のちに学長になりました。言うこととすることが違うように思えました。給料と手当てまでもらいながら、入学式も欠席、学校もろくに行かないまま、修了、そんな僕が偉そうなことを言えるとも思えませんが。

そして、この修士論文が残りました。

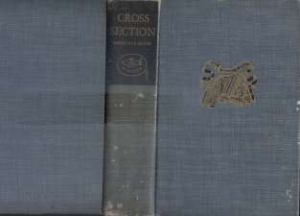

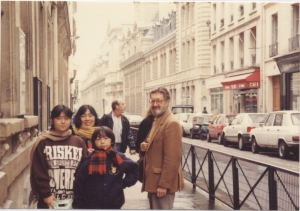

1年目の夏に、ファーブルさんの伝記の文献目録のコピーを持って、シカゴとニューヨークの古本屋と図書館をまわりました。ニューヨークの古本屋で、この修士論文の軸にした「地下にひそむ男」が載っている1944年のCroos-Section誌の現物を見つけたのは、大収穫でした。最初のアメリカ行きでしたが、言葉もしゃべれず、食べるものも口に合わなかったものの、アメリカにもそれなりの良さがあると思ったような、思わなかったような。

高校教員をやりながら、読む時間も書く時間も取れないまま毎日を追われるように過ごしていましたが、離れて初めて、活字と向き合える時間が持てました。

大学に書くための空間を求めてと自己弁護をしながら、高校には戻りませんでした。しかし、途中から入れてくれる博士課程もなく、どうしようと思いながら、ま、折角時間が出来たんだからと、長男の母親役と家事をやりながら、読んだり書いたりの生活をするようになりました。

本文 Richard Wright and His World

(作業中↓)

A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate Course at Hyogo University of Teacher Education

In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Education by Yoshiyuki Tamada

(Student Number: 81226)

Hyogo University of Teacher Education, December 1982

<修士論文表紙>

Contents

Chapter I Introduction・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 1

Chapter II Racial Protests

2.1 Big Boy and others who are no longer “Uncle Tom" in Uncle Tom’s Children (1940)・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ ・・・・・・・・・・・・・2

2.2 Jake Jackson who is like “a squirrel turning in a cage" in Lawd Today (1963)*・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 7

2.3 Bigger Thomas who makes a “rebellious complaint" in Native Son (1940)・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 11

Chapter III Beyond Racial Protests

3.1 Fred Daniels who has “got to hide" in “The Man Who LivedUnderground (1944)・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 19

3.2 Cross Damon who makes a desperate “groan" in The Outsider (1953)・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 25

3.3 Erskine Fowler who “sins a second time" in Savage Holiday (1954)・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 30

3.4 Rex Tucker who is “leaving" for Paris in The Long Dream (1958)・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 34

Chapter IV

Conclusion・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 38

Bibliography

* a posthumous work

Chapter I

Introduction

Richard Wright (1908-60) is generally labeled as a black protest writer on American white racism, but the works after “The Man Who Lived Underground" (1944) suggest that he makes determined attempts to step beyond mere racial protests without reconciling himself to the estimation.

The theme of this article is on the world of Richard Wright of whom we cannot form a fair estimation if we label him only as a protest writer, by way of tracing the protagonists in his major fictions. The protagonists with whom we are to deal in this paper are Big Boy and others in Uncle Tom’s Children (1940),1 Jake Jackson in Lawd Today (1963),2 Bigger Thomas in Native Son (1940), Fred Daniels in “The Man Who Lived Underground" (1944),3 Cross Damon in The Outsider (1953), Erskine Fowler in Savage Holiday (1954), and Rex Tucker in The Long Dream (1958). The first three are to be dealt with in Chapter II under the title of Racial Protests and the rest are in Chapter III under the title of Beyond Racial Protests.

Chapter II

Racial Protests

2.1 Big Boy and others who are longer “Uncle Tom"

<アンクルトムの子供たち表紙>

Much attention is to be paid to one of the two epigraphs in Uncle Tom’s Children so as to understand the stories:

The post Civil War household word among Negroes — “He’s an Uncle Tom!”— which denoted reluctant toleration for the cringing type who knew his place before white folk, has been supplanted by a new word from another generation which says — “Uncle Tom is dead!”

In the epigraph Wright hints to us that the protagonists in the stories are no longer “Uncle Tom."4 In what sense are they no longer “Uncle Tom" though they are Uncle Tom’s descendants without any doubt?

Big Boy5 is not an “Uncle Tom" in the sense that he flees from his native South to the North for his survival. His readiness to defend himself urges him to kill a white man, who rushes to his fiancēe wildly screaming to see four black boys swimming naked in the pond where no black is allowed to trespass. The murder forces him to have the alternative of death or flight; the death will force him to sacrifice his life in the face of a white mob; the flight will lead him to the loss of his native land and his family. His choice is restricted between the reluctant submission to the whites as a “nigger" and the flight from his society as a “black boy." In startling contrast to Dixie, with the sun shining all the time and sweet magnolias in full bloom at everybody’s door, what he sees across the “line" between the two races is beyond his imagination. Two of his mates are shot to death on the spot by the white man and the rest burnt to death by the white mob, with his tarred and feathered body twisted in agony. Narrowly escaping death from the mob, Big Boy leaves home for the North by choosing the flight as a “black boy."

Mann6 is not an “Uncle Tom" in the sense that he prefers death to his submission to the whites. He is caught in a dilemma twice. The first time is when his brother-in-law returns with a boat stolen from a white man; if he uses it, he will be put in some trouble with the whites; if not, his wife will suffer more and his family will be washed away by the flood. He decides to use it and begins to battle against the steering currents of muddy water, only to be confronted by the white man whose boat has been stolen. The man claims the boat at his gun point, which forces Mann to shoot him back. Mann inevitably kills him to defend himself and save his family. The second time is when he is put in a rescue work by the authorities. He happens to find the family of the white man, whom he has killed, in an imperiled house. He faces a dilemma; if he saves them, he may be accused; if not, they will be washed away by the raging flood. Mann reluctantly saves them, for he has neither the courage to kill them nor the will to flee from the village. In the hills of refuge he is accused by them and condemned to death by the authorities. He is a strong man in the flood, but he is only a helpless “nigger" before the whites. Mann, however, chooses to die, shot in the back, before being lynched by the mob, muttering to himself: “Ahll die fo they kill me! Ahll die…."7

Sarah8 is not an “Uncle Tom" in the sense that she sees her husband fight defiantly to death against a white mob. She surrenders herself to a white salesman who comes to her farm while her husband, Silas, is in town to sell his cotton. She knows in her heart that she cannot refuse his seduction in a way, for she always feels lonely because of her former lover whom she still remembers in secret, and because of her husband who is too busy himself in getting rich to care for her. When he discovers his wife’s betrayal, Silas utters furious cries, shattered: “The white folks ain’t never gimme a chance!…They take yo lan! They take yo freedom! They take yo woman! N then they take yo wife!" (125) Next morning when the salesman returns with his friend, Silas shoots on the spot the salesman whose friend barely escapes to the town, which forces Silas to have the alternative of fight or flight. Though she begs him to flee, he chooses the fight, making his final groan: “…Lawd….Yuh die ef yuh fight! Yuh die of yuh don fight! Either way yuh die n it don mean nothin …." (125) Silas kills as many whites as he can, before the mob sets fire to his house. In a nearby hill Sarah sees her husband live briefly with dignity as a “black man" without surrendering himself to the whites, for she knows Silas stays inside and burns to death without a murmur.

Dan Taylor9 is not an “Uncle Tom" in the sense that he resists against a white oppression. Taylor, a black preacher, cannot act in a crisis; his hungry people beg him to persuade white relief authorities to provide them food; Deacon Smith, eager to get his position in the church, stirs up his congregation against him; both the Mayor and the police demand that he should try to dissuade his people from joining a hungry demonstration. In the dilemma he cannot act. It is, however, his physical ordeal by a mob who torture him that makes him decide to act. When his son reproaches him openly for his reluctant attitude, he shifts his religious duty to his social action. He leads his people to the demonstration, marching on to the City Hall, crying out exultingly: “Freedom belongs t the strong!" (180)

Sue10 is not an “Uncle Tom" in the sense that she sacrifices herself to the faith of her own, by resisting against the white authorities. Sue, a religious widow, has two sons, Sug and Johnny-Boy. Sug is now in jail because of his Communist activities and Johnny-Boy takes over Sug’s tasks with Mother’s aids. Influenced by her sons, she has got a new faith; she has converted Christianity into Communism, for she loves her son. Her faith is tested by white oppressors. When city officials are determined to root out all the Reds, she is forced to confess when and where a planned meeting of Communists is to be held and who are to join it. The sheriff and his men threaten and torture her till she has fainted, but she never yields to them. Unfortunately she lets herself be persuaded to show the identity of the members by a white Communist informer. Soon she realizes her mistake and goes out to the woods to prevent the traitor from blurting out the names to the authorities. In the woods she is forced to confess the names before her son groaning in agony, with his legs and eardrums broken, but she never surrenders herself to the mob even in agony. Sue, with a gun hidden in a sheet, shoots the traitor who appears later, but Sue and Johnny-Boy are inevitably murdered by the mob.

The stories thus suggest that none of the protagonists are in the nature of an “Uncle Tom"; Big Boy flees from his native South because he kills a white man for self-defense; Mann is shot to death because he murders a white man to defend himself and save his family; Sarah sees her husband burnt to death because he shoots a white man in revenge; Taylor is tortured because he refuses to obey the whites; Sue is murdered because she resists against the white authorities. In the stories Wright gives considerable emphasis to the point that they are the new generation who are not “Uncle Tom." It is because he regards the new generation as a faint hope for the liberation of the oppressed blacks though the solutions are not necessarily offered as a way out of their plight. Through portraying the helpless blacks in a white world, he shows the Southern white oppressors how the racial injustice forces the blacks to live their humble and miserable lives. The depictions make us feel both his pity and anger. The pity is taken on “the degraded, the poor and oppressed who in the face of casual brutality, cling obstinately to their humanity."11 The anger is shown against the whites who have long oppressed the blacks in the rural South, where he himself has been forced to learn the ethics of living Jim Crow.12 With the combined pity and anger he directs his strong protests against the living Jim Crow in the brutal South which drives the blacks into inhuman conditions. The considerations we have given lead us to the conclusion that the stories of Big Boy and others are among the works of his racial protests, in which he makes a social comment on white racism in the South.

2.2 Jake Jackson who is like “a squirrel turning in a cage"

In the night shift-work Jake and his friends complain as follows:

'It’s hard to just move your hands all day and not see what you doing.’

'Like a squirrel turning in a cage.’

'This kind of work’ll drive a guy nuts.’

'I’m thinking he’s nuts when he takes a job like this.’

'That ain’t no lie.’13

The complaints guide us to right reading of the story of the black hero, Jake Jackson, who is dissatisfied with his present job. There are various causes of his dissatisfaction. A cause is due to the fact that the postal work is not the very job he yearns for. He eventually makes efforts to apply himself to memorizing the train schedules to get work as a railroad conductor, but only finds himself disappointed at his failure. He always has “no real ambition that can be translated into positive action."14

Another cause is formed by the contents of the job in the post office, in which he finds no satisfaction either in the process or after the work.

The unsatisfactory work consumes his energy, physical and mental, and makes him feel that even time passes more slowly than usual in the work time.

A third cause is to be sought in the bad working conditions in the post office as is suggested in the following text:

…All I could see right now was an endless stretch of black postal days; and all he could feel was agony of standing on his feet till they ached and sweated, of breathing dust till he spat black, of jerking his body when a voice yelled. (102-103)

…For eight long hours a clerk’s hands must be moving ceaselessly, to and fro, stacking the mail. At intervals a foreman makes rounds of inspection to see all is well. (113)

In the conditions he is forced to do the tedious work day after day.

The last cause, effective of all, is to be attributed to the invisible segregation in Chicago where he lives. Though finding no written rules of segregation, he always feels abused in one way or another. In the office “black men and women work side by side in the same post office jobs,"15 a curtain divides the two races, the blacks and the whites. His following dialogues with his companions give us a clear picture of the subtle segregation in Chicago:

'When a black man gets a job in the Post Office he’s done reached the top.’ (103)

'No white man wanted to work nights and breathe all this dust.’

'Look like the white folks don’t want us have nothing.’ (115)

'The white man’s Gawd in this land.’

'If they says you live, you live.’

'And they says you die, you die.’

'The only difference between the North and the South is, them guys down there’ll kill you, and these up here’ll let you starve to death.’

'Well, I’d rather die slow than to die fast!’ (156)

The implicit segregation thus deprives Jake of any hope and direction.

His wife, Lil, is another cause of his dissatisfaction. She has been ill since he tricked her into having abortion. Her illness presents to him various difficulties, such as his sexual frustrations and the deep amount of debt to the family doctor. Of all, the chief difficulty is that she will no longer trust him due to his betrayal. Dissatisfied with both his job and wife, he always attempts to release his frustrations temporarily through using violence toward his wife, playing gambles, telling dirty jokes, and going to a brothel for drinks and women with his companions.

In the story Wright shows us two problems. One is his active warning toward the blacks who are unconsciously blinded by American materialism and deluded by the prejudices. He reveals how American materialism blinds the blacks by depicting Jake as a brutal, lustful, and contemptible character. He is not so heroic as some heroes in Uncle Tom’s Children who fight back defiantly in their different ways against the whites. He is brutal enough to use violence toward his weak wife, lustful enough to indulge “his appetites with outrageous selfishness," and contemptible enough to dress fastidiously even when he is deeply in debt. The depictions about Jake reminds us of the following letter from Margaret Walker to Wright:

…I am beginning to see more and more every day the tragedy of Lawd Today: It’s right in my face….Everything is just as you have written it….Drinking and playing bridge, and living above their means, straining and bragging….16

He also reveals how their prejudices keep them from being aware of what they are by giving Jake a vulgar, prejudiced, and shameless character. He is vulgar enough to mutter to himself as follows: “Yeah, too much reading’s bad. It addles your brains, and if you addle your brains you’ll sure have book-worms in the brain." (62) And he is prejudiced enough to denounce the only Communist who appears in the novel, saying, “Nigger, You’d last as long trying overthrow the government as a fert in a wind storm!" (54) And he is shameless enough to make the following remark on his own race: “Niggers is just like a bunch of crawfish in a bucket. When one of 'em gets smart and tries to climb out of the bucket, the others’ll grab hold on 'im back…." (55) Through pointing out their blindness and prejudices he lays emphasis upon “the necessity for political education to make masses aware of their plight." (Quest, 154)

The other is his passive protest which he directs against the whites who have driven the blacks into their plight. Though he voices no explicit protest, the depictions of their plight suggest that the blame of the plight should be placed upon the whites who have long segregated in every subtle way; they have deprived the blacks of a fair chance of education; they have spoiled the blacks with American blind materialism; their implicit segregation has deprived the blacks of any hope and direction in life.

From all these considerations we draw the conclusion that the story of Jake Jackson is among his protest works against racial injustice and prejudice, in which he gives his active warning toward his own race and at the same time makes his passive protest against the whites.

2.3 Bigger Thomas who makes a “rebellious complaint"

The epigraph to Native Son runs as follows:

Even Today is my complaint rebellious,

My stroke is heavier than my groaning. -Job

The epigraph contributes effectively to our understanding of the black hero of the story, Bigger Thomas, who is “fated to live a never-ending debate" due to his “complaint," like Job in the Bible, and who is finally driven into the murder of a white girl, Mary Dalton. What kinds of complaint drive him into the rebellion? There are three factors of his complaint.

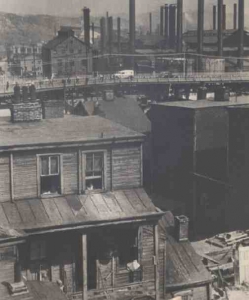

The first factor is the bad conditions in the Black Belt of Chicago’s South Side, where he lives with his family in a rat-infested one-room apartment as most black people do. The room is too small, dirty, and old to have any way of his own; he has no privacy. For such a nasty room he is charged eight dollars a week, which is equivalent for 40% of his weekly wage. Though there is no written law on segregation in Chicago, a “line" is strictly drawn between the two races. Black people are not allowed to cross the “line." It is at the Daltons’ where he is taught the difference between the two worlds. “Whereas everything at Bigger’s is loud, crowded, and collapsing, at the Daltons’ it is subdued, expansive, and expensive." (Hero, 68-9)

The second factor is the black people he lives with in the Black Belt. Every day his mother makes her bitter and loud complaints against Bigger who lives his idle life without taking a job which the relief authorities offer him. Her complaints only makes him feel sick of his life at home. What makes him feel more disgusted is her attitude toward life with which she accepts her misery quietly; she already gives up her hope of living in the world. Such is the case with his friend, Bessie. When she is forced to flee with Bigger who already kills Mary, she feebly moans as follows: “…all my life’s been full of hard trouble….I just worked hard everyday as long as I can remember, till I was tired enough to drop, then I had to get drunk to forget it."17 She has quietly accepted her misery as his mother has done. It is also the case with his companions. They make bitter complaints to their misery, but find no positive way of a protest. What they can do is playing “a game of playing-act" in which they imitate the manners of white folks or making a plan of the robbery in vain. They all accept their misery too quietly. As he cannot accept his misery unless he lays “his head upon a pillow of humility," he holds “an attitude of iron reverse" toward them denying himself. It is because “he knew that the moment he allowed what his life meant to enter fully into his consciousness, he would either kill himself or someone else." (9)

The third factor is the white people with whom he is thrown into contact after taking the job at the Datons’. They regard him as a “nigger" or as an example of the oppressed minority, not as a man. Mr. and Mrs. Dalton, rich owners of many buildings in the Black Belt, view him only as a timid uneducated black boy whom they have given a chance as a supporter of National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Though they have offered him a job and a neat room, they never suspect that their hypocritical attitudes make him feel uneasy, tense, and miserable. Mary Dalton and Jan Erlone, young Communists, reckon him only a sample of the oppressed blacks and a potential member of the Party. Though they are liberal enough to shake hands with and drive him to the Black Belt to take dinner together, they don’t know that their progressive attitudes drive him into fear and hatred. Britten, a private detective employed by Mr. Dalton, considers him to be a “nigger." He never sympathizes with black people, for to him “a nigger’s a nigger" and “niggers" don’t need a chance.

The factors make his complaint rebellious, which carries him to the murder of Mary. Although he suffocates Mary to death for fear of being discovered by her blind mother who appears unexpectedly and ghostly at Mary’s room, it seems to him that his murder of Mary is not accidental in a true sense. Before he calls at the Daltons’, he says to his friends as follows: “….every time I got to thinking about me being black and they being white, me being here and they being there, I feel like something awful’s going to happen to me…." (17) After the murder of Mary he reaches the following conviction: “…in a certain sense he knew that the girl’s death had not been accidental. He had killed many times before, only on those other times there had been no handy victim….he felt that all his life had been leading to something like this." (90) Bigger has thus come to regard the murder of Mary to be a form of his rebellion. To him the rebellion has a double sense. One is his positive rebellion against the whites who have oppressed the blacks for centuries. The other is his passive rebellion against the oppressed blacks who have accepted their misery too quietly. Bigger never feels sorry for Mary: on the contrary he feels that the murder is “more than amply justified by fear and shame" which Mary made him feel. The murder even adds to him “a certain confidence which his gun and knife did not."18 The confidence produces a new perspective with which he can realize that a lot of people are blind; they do not want to see what others are doing if that doing does not feed their oven desire. The confidence and the perspective guide him with a plan to get ransom money from the Daltons by making it appear that Jan and other Communists kidnapped Mary, for he knows that Mr. Dalton and others have prejudices against blacks and Communists; to them “niggers" are too timid to have such a plan and “Reds" are crazy enough to commit such a crime. The offense of the murder of Mary brings him “the sense of fulness" which he has never felt. To him the offense is among “the first full actions" and “the most meaningful, exciting and stirring things," for he already finds no meaning in life as is shown in his following confession: “everything I wanted to do I coudn’t….I just went to bed at night and got up in the morning. I just lived from day to day." (301) The acts carry him into another murder of Bessie because she stands in his way of flight from the police. When he kills her, he feels that he has created “a new world for himself."

Few people in the story can understand his way of life. Buckley, the State’s attorney, and the reporters proclaim that Bigger is a rapist, emphasizing his race and his bestiality. In the jail, Hammond, a black preacher, attempts to persuade him to kneel before God. Bigger’s sister, Vera, sobs and complains of her misery brought by her brother’s crime. His mother asks him to pray to God. The sights of the black people make him feel sick. Crushed with shame and anger, he groans as follows: “They ought to be glad!…They ought not stand here and pity him, cry over him; but look at him and go home, contented, feeling that their shame was washed away." (252) Jan and Boris Max alone try to understand and help him. In the trial Max, a Communist lawyer, analyzes Bigger’s crime as follows:

…did Bigger Thomas really murder?…If it was murder, then what was the motive?…The truth is…there was no motive as you and I understand motives within the scope of our laws today. The truth is, this boy did not kill….He was living, only as he knew how, and as we have forced to live. The actions that resulted in the death of those two women were as instinctive as breathing….It was as act of creation! (335)

He pleads of sending Bigger to prison for life as the best way of the first recognition of his personality, but Bigger is sentenced to death under the laws of the State. Though he makes efforts to plead for Bigger, Max has not seen all; though he can see the racial situation in general, he cannot see the individual in the mass.

Through the story of Bigger Thomas, Wright tries to show us four problems. The first problem is his protest against the whites who have oppressed the blacks for a long time. By borrowing the phrases of Max who makes powerful and subtle analyses of Bigger’s crime on historical, economical, and social backgrounds, Wright makes it clear that Bigger is a native son America has produced, and that it is not on Bigger but on Mr. Dalton and white Americans that Bigger’s crime should be blamed rationally. It is because Mr. Dalton is an exploiter of the poor blacks by renting houses, though he contributes much money for Negro education as a supporter of NAACP in order to ease the pain of his conscience, and because the white Americans have helped to keep the blacks within rigid limits. The protest implies the warnings against the whites; the whites do not acknowledge what their racism has produced, a second and a third “Bigger Thomas" will appear; even if the whites try to make the blacks avert their eyes from racial acts of violence by giving the limited charities as Mr. Dalton has done, the time will never come when the solution is to suggest itself to them.

The second problem is his warning toward the blacks who have long accepted their misery too quietly. Wright depicts most black characters as contemptible persons as Jake Jackson in Lawd Today. Bigger is too poor-educated and unintelligent to know what the society is. His companions are too pointless and hopeless to live their own lives, only indulging their appetites with selfishness day in and day out. Bessie and his mother are too helpless to find any hope in life. They try to find some escape from their everyday sufferings by drinking and praying. They never realize what they are, even when Bigger feels that he has washed away “their shame" by the murder of Mary. His sister moans her misery; his mother and a black preacher attempt to persuade him to pray to God. They are too blind to know the fact that the whites make efforts to defend themselves from racial violence by forcing the blacks to adopt religion as the means of solacing their sufferings. In that sense the following comment by Redding is to the point: “…They (Negroes) did not want to believe that they were helpless, as outrageous, as despairing, as violent, and as hate-ridden as Wright depicted them. But they were."19 What Wright depicts is a manifestation of his warning toward his own race; as long as they find same escape and accept their misery quietly, they cannot free themselves from the white oppression; they should make efforts to find any way of self-education without making constant complaints in vain. The third problem is about the perspective which Bigger has gained through the murder of Mary. It is not until he murders Mary that he realizes that a lot of people are blind. Most black people make complaints of their sufferings, but never realize what they are. Most white people help to keep the blacks within rigid limits, but never realize what their segregation has produced. In his essay Wright states about the matter as follows:

If I were asked what is the one, over-all symbol or image gained from my living that most nearly represents what I feel to be the essence of American life, I’d say that it was that of a man struggling mightily to free his personality from the daily and hourly encroachments of American life. Of course, Native Son is but one angle of what I feel to the struggle of the individual in American for self-possession.20

The last problem is the revelation of his “ultimate break with the Communist Party."21 In the story Wright portrays Max as a lawyer who has not seen all of Bigger’s crime. Max “sees Bigger as one black man among twelve million, not as a boy suddenly aware of his own identity. He understands the case of the crime, but not what it means to Bigger."22 The story implies his break with the Party with which Wright is to deal later in The Outsider in details.

With all this taken into consideration, we conclude that the story of Bigger Thomas is among his racial protests in which he makes a strong protest against the whites and at the same time gives warnings toward his own race.

Chapter III

Beyond Racial Protests

3.1 Fred Daniels who has “got to hide"

クロスセクション誌と青山書店大学用テキスト

The story begins with the mutter of the black hero, Fred Daniels: “I’ve got to hide,…"23 The mutter echoes through the story and gives us an important clue to it. His hiding implies two levels of reality, objective and subjective. The former indicates what drives him into the underground and what his hiding means. The latter indicates what he sees there.

What drives him into the underground and what does his hiding mean? The scene in the sewer where he remembers his past tells us his situation; he was wrongly arrested, accused of the murder, and forced to sign a confession by the police. His surrender means his death, unavoidable because he is sentenced to death under the white law. He realizes his situation so instinctively that he prefers life to death by running away from the authorities. When he happens to see a manhole cover leap up on the street, he hatches a plan of hiding in the sewers and goes down through the manhole into the underground. The very fact of his being accused of the crime means that he is denied by the society and excluded from it. The fact of hiding in the sewers means that he denies the society in value. Fred is now “a human in unreal, inhuman context" (Quest, 241) and a man who “is no longer deluded by the aboveground values."24

What does he see in the sewers with his own eyes? Under the ground he sees many kinds of “the reverse of reality." (Quest, 240) From the crevice of the sewer wall he sees a black church service. Seeing them singing and praying, he feels an irrestible impulse to laugh at their blindness, thinking that “they oughtn’t do that." Although he has a vague feeling that “those people should stand unrepentant and yield no quarter in singing and praying," he does not know the reason. Later when he revisits the church, he realizes the reason; “their search for a happiness they could never find made them feel that they had committed some dreadful offense with which they could not remember or understand." (85)

Another kind of “the reverse of reality" is reflected in the sewer, where he catches a glimpse of a nude baby of “nagged by debris and half-submerged in water." The baby is floating, with its eyes closed “as though in sleep," its fists clenched “as though in protest," and with its mouth gaped “in a soundless cry." When he finds the baby dead, he feels “the same nothingness" he felt while seeing the people singing in the church.

A third kind of “the reverse of reality" he finds in a movie house is “a stretch of human faces, tilted upward, shouting, whistling, screaming, laughing." The sight makes upon him a touching impression which is akin to the same kind of compassion that he felt before in the church. The vast “sea of faces" makes him aware of their mere “laughing at their lives" and of their mere “yelling at the animated shadows of themselves."

Then comes the last phase of “the reverse of reality" in a jewelry firm, where he sees a man open a huge safe filled with more money and jewelry than he has ever seen and feels like stealing them by getting the dial combination of the safe. It is only a symbolic act of defiance to the world that he wants to get them. It is not that he considers them to be of great value to him but that, paradoxical this may sound, he regards them as of no worth. He patiently waits till the safe is opened once again. He finally sees a man open the safe and steal some of the money, which makes him feel indignant “as if the money belonged to him." After that he steals the rest of the money, but does not feel guilty, for his instinct tells him that his stealth of the money is different from that of the man in motive; he has no intention of spending the money away; the man, who must be an employee of the firm, is to spend it for pleasure. Later when he revisits the firm, he sees a night watchman being accused of the robbery of which he is innocent. The accusation leads to the suicide of the convicted, on which he hears the policemen making observations in this way: “Our hunch was right," adding that “He was guilty," and that “Well, this ends with the case." (88) A keen sense of “the reverse of reality" leads him to the conclusion that the aboveground is an absurd world “fundamentally marked by chaos and disorder and blind materialism."25; in the church the people are blinded by the delusions; in the sewer the innocent baby is floating in debris; in the jewelry firm the employee steals the money and the watchman is wrongly accused and tortured by the policemen.

From the building he creeps into, he brings back many articles into the cave which he finds in the sewers. In the cave he plays games with the loots, plastering walls with green bills, hanging watches and others on the walls, and dumping diamonds and coins on the dirty floor. The games symbolize both his defiance to the blind materialism and mockery of the values on the aboveground as is shown in the text: “…the cleaver, the radio, the money, and the typewriter were all on the same level, all meant the same thing to him….They were the serious toys of the men who lived in the dead world." (77) Before the loots, he reflects on his experiences: “…he remembered the singing in the church, the people yelling in the movie, the dead baby,…He saw these items hovering before his eyes and felt that some dim meaning linked together…." (79) Fixing, a steady gaze on the papered walls, he broods: “…between him and the world that had branded him guilty would stand this mocking symbol. He had simply picked it up, just as a man would pick up firewood in a forest. And that was how the world above ground now seemed to him, a wild forest filled with death." (81) He resumes brooding:

…Why was this sense of guilt so seemingly innate, so easy to come by, to think, to feel, so verily physical? It seemed that when one felt this guilt one was reacting in one’s feeling a faint pattern designed long before; it seemed that one was always trying to remember a gigantic shock that had left a haunting impression upon one’s body which one could not forget or shake off, but which had been forgotten by conscious mind, creating in one’s life a state of eternal anxiety. (85)

And finally he discovers that all men are guilty because they are human, and that “all men are responsible for their actions in a world of evil and absurdity, and that men must accept responsibility for their existence nevertheless." (“Identity," 52) Fred can be said to have gained a new personality by descending underground, a new perspective that “all men are guilty because they possess an inherently evil nature," (“Identity," 52) but they must be responsible for their deeds nevertheless. The new perspective urges him to go back to the aboveground to proclaim his discovery. His readiness to tell it to the people cannot find its justification due to his violent death by one of the policemen who says after shooting as follows: “You’ve got to shoot his kind. They’d wreck things." (102)

Through the story of Fred Daniels, Wright shows us his new views which he has never offered in his previous works. In those works he has laid too much emphasis on what racism has produced-what the two races are, not on what blackness is – what blackness means; in Uncle Tom’s Children he has put his finger on the terror of direct white oppression in the rural South, by giving a clear picture of the new generation who obstinately cling to their humanity in the face of the white brutality; in Lawd Today he has indicated the brutalization of black life in the urban North, by portraying an ordinary black worker who is dejected by the subtle segregation and spoiled by blind American materialism; in Native Son he has pointed out what racism has produced, by depicting a native son who has gained his self-consciousness through the offense of the murder. In those works he has given too much weight to “those moments when the black and white worlds interact with, or react to, each other." (Works, 28) On the contrary in this work he has laid more emphasis on what blackness is what blackness means than on what racism has produced. It is due to his conviction that “the black man can recognize the absurdity of the world more rapidly than others" (“Identity," 52) that Wright portrays the hero as a victim of a racial society at the beginning of the story. Fred, who is condemned and shot to death, mirrors “the dilemma of all black Americans, who are both part of America and excluded from it." (Quest, 241) Fred is “a kind of negative American" about which Wright states in White Man, Listen!:

…The American Negro’s effort to be an American is a self-conscious thing. America is something outside of him and he wishes to become part of that America…. But…since he lives amidst social conditions pregnant with racism, he becomes an American who is not accepted as an American, hence a kind of negative American.26

The story, however, enters upon the second phase of the plot as soon as Fred descends underground. Under the ground he is omnipotent and can view the people above ground from the vantage point, for they do not realize that they are being observed. Fred is now an outsider “whose color is no longer important." (Quest, 240) Fred, who is forced to flee in the sewers, is merely an aviator of the oppressed minority indeed, but Fred, who has returned back to the aboveground with the new perspective and personality, is an aviator of all men. Therefore the message from Fred Daniels is the universal one. Through Fred Daniels Wright sends to us the following message: “only the acceptance of one’s responsibility in an absurd world can result in self-realization." (“Identity," 52) The message is Wright’s “great concern with meaning, with identity, and with the necessity to remain sane in a society where the individual personality is denied and the world appears devoid meaning.”27

These considerations lead us to the conclusion that the story of Fred Daniels is not only a racial protest but a universal quest of “nature and evil" and of “the problem of identity to all mankind," in which Wright has made an attempt to step beyond mere racial protests by giving more weight to what blackness means than to what racism has produced.

3.2 Cross Damon who makes a desperate “groan"

The Outsider 表紙

“He buried his face in his hands, closed his eyes and groaned; 'God …"'28 – this is the depiction of the black hero, Cross Damon when he calls on Eva Blount. What makes him groan? Eva is an efficient painter but her work and freedom are already ruined by her husband Gil, a Communist leader, who was ordered to marry her to get her into the Party for prestige purpose. When Lionel Lane (Cross’ false name in New York) is brought by Gil to their apartment, Eva pities him at first, for she considers him to be the same innocent victim to the Party as she is. But he is rather a “willing victim" that an innocent one, for he tries to use the Party as the contemporary comflage behind which he can hide from the law, as Gil uses Cross for the Party.

In Chicago Cross encountered a subway accident one day, when he barely escaped uninjured from the mess. Later when he heard the radio announce his death wrongly, he hit upon a plan of accepting the accident which would wipe out his practical problems. He was an intellectual young postal clerk, who had dropped out of Chicago University. At that time he was completely in plight economically, physically, and mentally – his wife with three sons was always complaining of alimony; his young mistress was urging him to marry; his religious mother was charging him coldly with morality; the alcohol was deadening the raw nerves of his stomach. In such a serious plight, Cross was too pessimistic to find meaning or values in the world. When he left Chicago for New York, he had already become a lawless outsider, living alone under his own laws. Under the laws he killed four men. First he killed Joe so as to maintain his new freedom, because Joe, whom he encountered at a cheap hotel in Chicago, was his postal friend – a symbol of his old world. Secondly he killed Gil and Herndon so as to blot out the dark image of the struggling men from the face of the earth, because both persons, a Communist leader and a total Fascist, were their own “little gods" and his enemies. Last he killed Hilton so as to defend himself from being accused of his murder, because Hilton was determined to make a convenient use of the bloody handkerchief, the proof of Cross’ murder.

In New York Cross uses the false name Lionel Lane and chances to be acquainted with the Communists. After her husband’s death Eva falls in love with Lionel Lane, who is not now what he was as he comes to know what it is to love another. Eva is to him a thread of hope with which he will be able to go on living. In the presence of such a woman the hero is to face which he should do: Should he make a confession of all his past? Should he be bold enough to go on with his life under the false name? Should he flee from Eva before she is aware of his identity? In such a dilemma there is nothing left for him but to make a desperate “groan": “God…" In the meanwhile Eva is taught what he is and has done by the Party leaders who take her to the Party headquarters. Back in the apartment she is told all the truth by Cross and gives desperate cries, edging away from him with horror: “…I thought you were against brutality – I thought you were going to tell me what Gil had done to you – I thought you hated suffering." (289) She no longer believes in him. However hard he tries to make an excuse for his infidelity, he finds it all in vain. Eva finally kills herself. Eva never understands an outsider Cross Damon. The only character in the story that is capable of understanding the hero Cross is Houston, the New York District Attorney. As he is in a sense an outsider because of a hunchback, he shares identical viewpoints with Cross. What he talks in earnest to Cross about an outsider goes as follows:

Negroes, as they enter our culture, are going to inherit the problems we have, but with a difference. They are outsiders and they are going to know that they have these problems. They are going to be self-conscious; they are going to be gifted with a double vision, for, being Negroes, they are going to be both inside and outside of our culture at the same time…. (129)

My deformity made me free; it put me outside and made me feel as an outsider. It wasn’t pleasant; hell, no. At first I felt inferior. But I have to struggle with myself to keep from feeling superior to the people I meet…. (133)

Later when he investigates the case of Cross’ murder, Houston insists that the case of Gil and Herndon is not “double manslaughter" but the murder by a third person – a man of lawless impulses, and then accuses Cross of the murder on psychological basis, after finding his real identity in Chicago. It is ironical that an outsider Houston accuses another outsider Cross. Cross has begun to have the truest relationship with Houston for the first time in his life, for Houston is the very man Cross has long sought for – Houston is the man who has become an outsider not because he was born poor and black, but because he thought his way through many veils of illusion. Houston releases Cross because he has no proof on material basis, but Cross is shot down by one of the Party members, who is afraid of him because they cannot understand him. When Houston rushes to the spot where Cross is shot down, Cross whispers to Houston as follows:

'I wanted to be free…, to feel what I was worth…what living meant to me…. I loved life too… much…’

'Never alone…. Alone a man is nothing…. Man is a promise that he must never break….’

'…We’re different from what we seem…. Maybe worse, maybe better…But certainly different…We’re strangers to ourselves.’

'Don’t think I’m so odd and strange…. I’m not…. I’m legion…. I lived alone, but I’m everywhere….’ (439-40)

Through the story of Cross Damon, Wright shows us three problems. The first problem is about a philosophical theme of an outsider – the theme of how an outsider should live in a society where he no longer finds any meaning or any value. Cross is not the only outsider, for Eva, Houston, Gil, Herndon, and Hilton are much the same in a sense; Eva is dejected by Gil’s betrayal; Houston is alienated by his physical handicap; Gil, Herndon, and Hilton are deluded by their blind ideology. The problem of an outsider is, therefore, a universal one, as is shown in Cross’ whispering to Houston in his death time: “I’m everywhere…." The problem implies a social comment on America and other Western countries whose civilizations have produced many outsiders, and at the same time gives implicit warnings to modern citizens governed by their culture. In the sense Hicks’ comment is to the point: “The Outsider is…a book about modern men….It challenges the modern mind as it has rarely been challenged in fiction…his principal problems have nothing to do with his race."29 Through the problem Wright deepens the theme dealt with in “The Man Who Lived Underground" – the theme that all men “must accept responsibility for their existence" (“Identity," 54) even in a world of evil and absurdity.

The second problem is about a “double vision" with which Wright widens the “underground vision" handled with in “The Man Who Lived Underground." With the vision Wright makes it clear that “the black man is able to recognize the irrational character of the world more rapidly than others" because of being driven underground by racism. Wright tries to “achieve universality by concentrating on the specific, by dealing with his experience."30

The last problem is about Wright’s personal relationship with Communism. Wright has tried to write Uncle Tom’s Children, Native Son, and other works on the belief that Communism is the means of the liberation of the blacks, but in this work he tries to repudiate the belief as is implied in Gil’s words: “We’re Communists. And being a Communist is not easy. It means negating yourself, blotting out your personal life and listening only to the voice of the Party. The Party wants you to obey." (183) It is the declaration of his personal break with the Party. Wrghit shows a slight sign of his personal break with the Party in Part III of Native Son, in which Wright gives a picture of a Communist lawyer Max who cannot see Bigger as an individual though he can understand him as a sample of the oppressed minority. In the sense The Outsider is the further quest of Native Son beyond which Wright tries to step.

Taking all these considerations into account, we conclude that the story of Cross Damon is among his larger quests of a man, in which Wright has tried to step beyond racial protests.

3.3 Erskine Fowler who “sins a second time"

The epigraph to Savage Holiday leads us to the solution of the story:

For he who sins a second time,

Wakes a dead soul to pain,

And draws it from its spotted shroud,

And makes it bleed again,

And makes it bleed great gouts of blood,

And makes it bleed in vain!

– Oscar Wilde’s The Ballad of Reading Gaol

In the case of Erskine Fowler, the white hero in Savage Holiday, his “sin" has a double sense. The primary sense is his real murder of Mabel Blake, a young widow with a son next door. The secondary is his psychopathetic murder by which the hero tries to disown the retained image of his own dead mother. In the latter case, the “concept of deeply buried desire that emerges thirty years later in the form of a crime places the murder itself on another, almost secondary level, since the remembered reality of Fowler’s childhood is revealed as the unreality of a dream." (Quest, 378)

Tony’s death is caused by Fowler’s faults, but is he responsible for the death in a true sense? On the morning when the accident happens, he finds himself locked out of his apartment, naked, for a sudden draft slams and locks the door behind him when he steps out to pick up his Sunday news paper scattered in the hall, before taking a shower. He dodges naked and terrorized through the buildings and finally rushes to the balcony, where Tony has been playing alone, in order to climb in through his bathroom window, but the sight of his loaning nude body startles Tony so terribly that Tony shrinks back against the railings and falls down from the tenth floor. His nudity is to blame indeed, but it seems to him that the way of Tony’s fright was too extraordinary. At first he cannot see why Tony was so afraid of him. On his second thought he comes to realize the reason: Tony thought that naked men were to attack his mother, for he always observed his mother making love with men. In that sense it is not Fowler but Mabel who is to blame for Tony’s death. He does not go to the police nevertheless; he cannot go. As he knows that others will not believe in his story, he decides to conceal the fact for self-protection. From then on a sense of fear and guilt begins to attack.

At that time he was already assailed by another anxiety. He was suddenly forced a premature retirement from an insurance company, so as to make room for the president’s son. Though he felt disgusted with the retirement, “what was fundamentally fretting him was that – now that he had retired and free – he didn’t know what to do with himself."31 To the displeasure is added another irritation due to the boy’s death.

Two reasons force their ways into an inevitable acquaintance of Fowler with the dead boy’s mother Mabel. One reason is given for his self-complacent sense of mission which he felt while preaching his sermon in Sunday School. The other is supplied for his fear that she might have seen his crime. Mabel, quite an opposite to his own character, at once attracts and disturbs him. “Her helpless state" caused by her son’s death blinds his judgement, and “her gestures of modesty" make him feel that she is “really kind of pure" even though he regards her to be a whore. He begins to “allow himself to be swamped by pity" and then finds himself trapped in a kind of love – “the more abandoned she was, the more he yearned for her." He finally decides to marry her, not to silence her, but to possess her entire being. But Fowler and Mabel are too different in every way. Fowler, a middle-aged rich man, is a Sunday School superintendent. Mabel, a young employee in a night club, is a kind of prostitute. His love-hate struggle begins. Her way of life irritates him. He cannot understand why she can go out for drinks, spend with a young man, and receive frequent phone calls in so tolerant way. Her degraded way of life reminds him of his own dead mother, for Mabel is so much alike the retained image of his mother. Mabel forced his son to live in constant terror of violence, by allowing him to watch her making love with many men. His mother made Fowler feel afraid and ashamed of men, with whom she had gone out even when Fowler had been ill in bed. He would have liked his mother to love him. He realizes that Tony was psychologically crippled. Combined love and hate of this sort ends in a kind of delirium, which brings about a desperate murder of Mabel. It is the only way he can possess her, and at the same time disown the retained image of his mother.

Four problems are presented to us in the story of Erskine Fowler. The first problem is on crime and guilt. Wright asks us which is guilty of Tony’s death, Fowler or Mabel, in a true sense, and which is to be blamed for the murder of Mabel, Erskine or his mother. For Tony’s death, Fowler is not to be blamed only because the death is accidental. But he is to blame both in the sense that after the accident he has “a wish that Tony died instantly upon his impact with pavement" for fear of being accused, and in the sense that he substitutes his faults for his self-complacent sense of mission. It is, however, not Fowler but Mabel who is to be blamed in a true sense, for She forced Tony to live in constant terror of violence. Of Mabel’s death Fowler is guilty, for he likes to possess her through the offense of the murder. But it is his dead mother who is to be blamed in a true sense, for it is the retained image of his mother that drives him into the murder of Mabel.

The second problem is on “mother." In the story Fowler has attempted to repudiate his mother’s image to disown the haunted image of his dead mother, placing the real murder on another level. The problem is another angle of The Outsider, in which Wright repudiates his psychological past throw Cross Damon who repudiates his mother on intellectual grounds. The third problem is on religion. In this work Fowler has tried to redeem himself by substituting his faults for a sense of mission. His religion adds to him even another anxiety without reducing his irritation. The depictions reflect on his mockery of the blindness of the men and on his implicit protests against Christianity.

The last problem is on freedom. It is not until he is fired from his job that he realizes what his freedom is. As Constance Webb points out, “his freedom has lain within the context of a job, a church, Ivy League clothes, money in the bank and an East Side address." (Webb, 316)

It is the problem of “a man struggling mightily to free his personality from the daily and hourly encroachments of American" with which Wright already deals in Native Son.

From these considerations we draw the conclusion that the story of Erskine Fowler is his new attempt of “completely non-racial, dealing with crime," in which he tries to step beyond racial protests.

3.4 Rex Tucker who is “leaving" for Paris

The Long Dream 表紙

“You scared, Papa! You scared too! Just like me!"32 Fish (Rex’s nick name) exclaims to his father Tyree, when he is released from the jail, where he has been put under the charge of trespassing into the white territory. What makes Fish call his father scared? Before the jail house trouble, Fish has a bitter experience. It is the lynching of Chris by the white mob. The lynch teaches Fish what a “race fight" means. In the “race fight" he sees his father trembling and scared in the face of the whites. The sight of his father makes him feel a nameless hatred toward his father. In the jail his father’s “act" before the whites makes Fish feel so humiliated that Fish comes to feel that he has no “father." Fish feels more shameful when his father says as follows: “A white man always wants to see a black man either crying or grinning. I can’t cry, ain’t crying type. So I grin and git anything I want." (142) Fish thus calls his father scared, casting reproach on his Uncle Tom’s role in the face of the whites. Tyree, however, does not keep silent when he is called a coward by his son. Tyree forces his son to answer whether Fish is to obey his father, saying, “Boy, look at what I done with my life! I’m black, but do you hear me whining about it? Hell, naw! I’m a man! I got a business, a home, property, money in the bank…." Tyree’s fury is unbridled enough to make Fish obey. Contented his son’s submission, Tyree takes his son to a whore house, where Fish sees another side of his father. He discovers that Tyree owns the whore house with the permission of the chief of the police and exploits the poor blacks by renting houses; Tyree is a cruel exploiter and a powerful leader of the black community; Tyree can handle with the chief of the police. Tyree guides his son to the white world, by giving the following warnings: “You are nothing because you are black, and proof of your being nothing is that if you touch a white woman, you’ll be killed." (157) The mob lynch and the jail house trouble enable Fish to see the ambivalance of Tyree’s personality, which initiates Fish from a boy to a man.

The most cruel incident Fish has experienced is the big fire of the whore house, which kills 42 people. The fire put Tyree and Cantley, the chief of the police, into a serious crisis, for Tyree runs the house, while neglecting the warning of the fire department and Cantley has continued to snatch bribes from Tyree for ten years. Tyree feels intuitively that Cantley is to escape from the crime because of being white, and that Tyree is fated to be a scapegoat because of being black. The desperate feeling urges Tyree to threaten Cantley with canceled checks, the only proof of the bribes. Tyree asks Cantley to put “six niggers" on the jury in his trial. The sight of two Tyrees – “a Tyree resolved unto death to save himself and yet daring not to act out his resolve" and “a make-believe Tyree, begging, weeping"-makes Fish feel something obscene. Cantley promises to help Tyree, but Tyree instinctively feels his own fate and makes a desperate rebellion against Cantley – he takes ,the checks to a white lawyer, McWilliams, and tells him as follows:

'I ain’t corrupt. I’m a nigger. Niggers ain’t corrupt. Niggers ain’t got no rights but them they buy….for years I done bought me rights from the white man and I done built a business….Now the same men who sold me rights ask me to give 'em all my money’ (273)

This is Tyree’s last desperate fight against the whites, which makes Fish feel as if Tyree “had draped about his shoulders an invisible cloak of authority,…" (284) Tyree, after all, is framed and shot to death by Cantley. After Tyree’s death, Fish is also framed and forced to stay in jail for two years by Cantley, for he is afraid of Fish’s checks which his father left for him. In the jail Fish finds himself acting an “act" before the whites as his father did. He realizes that his father has already become “shadow of himself." When Fish is released from the jail, Cantley advises Fish to take over Tyree, but Fish makes up his mind to flee Paris where “folks don’t look mad at you just cause you are black" (360) and says a farewell to his dead father: “Papa! I’m leaving….I can’t make it here." (377)

In this work Wright’s effort is focused on the father-son relationship between Tyree and Fish-Tyree who lives his own life, grinning, and Fish who grows up to be a man under his father’s guidance. The chief aim is made to depict the reason why Fish should leave his native South for Paris. The depictions show us that “Fishbelly’s dream of identifying with white values can never be realized under existing circumstances." (Art, 151) Though in this work Wright sets the plot in the South as in Uncle Tom’s Children which is written with his aim of active protests against the white brutality, this work is not the same in motive with Uncle Tom’s Children. It is because this work is written in view with the aim of Part I of the trilogy, in which Fish’s life in non-racial situation is to be portrayed in details. The view is confirmed with the fact that another part of the trilogy was published in three years after Wright’s death, in which the exile life of Fish was to present itself.

The conclusion we arrive at is that the story of Rex Tucker is “a solid foundation for his new departure" (Quest, 475), in which Wright tries to step beyond racial protests.

Chapter IV

Conclusion

In Uncle Tom’s Children Wright shouts strong protests especially against the whites by depicting Big Boy and others who are not in the nature of an “Uncle Tom," with emphasis laid on the terror of direct white oppression in the rural South. In the work he shows his profound pity toward his own race by giving a picture of the new generation who obstinately cling to their humanity in their different ways in the face of the white brutality, with hope laid on the liberation of the oppressed blacks. In Lawd Today, contemporary with Uncle Tom’s Children, he also makes protests against the whites by portraying Jake Jackson dejected by the subtle segregation in Chicago and spoiled by blind materialism, with weight given to the brutalization of black life in the urban North. In the work he gives warnings toward his own race by giving a clear picture of ordinary black workers unaware of what they are, with emphasis to “the necessity for political education to make the masses aware of their plight." Both works are based on his following conviction stated in “Blueprint for Negro Writing" (1937):

…for the Negro writer, Marxism is but the starting point. No theory of life can take the place of life. After Marxism has laid bare the skelton of society, there remains the task of the writer to plant flesh upon those bones out of his will to live. He may, with disgust and revulsion, say no and depict the horrors of capitalism encroaching upon the human being. Or he may, with hope and passion, say yes and depict the faint stirrings of a new emerging life.33

Following his “blueprint," Wright depicts “the faint stirring of a new emerging life" in Uncle Tom’s Children “with hope and passion." While in Lawd Today he depicts “the horrors of capitalism encroaching upon the human being" “with disgust and revulsion."

The intensity of the protests and warnings shown in the two works increases in Native Son. Through the story Bigger Thomas who is finally driven into the offense of the murder of a white girl and a black girl, Wright both directs active protests against the whites and extends passive warnings toward the blacks. The combined protests and warnings confirm us that Bigger is a native son America has produced, and that both the blacks and the whites are blinded by too heavy daily and hourly encroachments to realize what they are. In the sense the following comment given by Felgar is to the point: “They (Negroes) did not want to believe that the America they loved had bred these pollutions of oppression into their blood and bone. Similarly whites did not and do not want to acknowledge what their racism has produced."34 The protests in Native Son are overwhelming enough in their power to extract their reluctant admission from both the blacks and the whites, but to our regret, the story makes us feel something important lacking. It is because the solution of the existing plight does not suggest itself to us in spite of a skillful presentation of the cause and the effect of the plight; Bigger, though he becomes aware of his identity by way of the offense of the murder, “still has not resolved the problem of how to get along in this world." (Hero, 94)

In the three works too much weight given to “those moments when the black and white worlds interact with, or react to, each other" (Works, 28) keeps Wright from depicting what blackness is; though he clearly portrays what racism has produced and what the blacks are, Wright does not pay much attention to what blackness means and how the blacks should live in the absurd world. On the contrary, in “The Man Who Lived Underground" Wright gives more weight to what blackness is than to what racism has produced, by depicting Fred Daniels who has gained his self-consciousness and new perspective in the underground where he hides because of being wrongly accused by the authorities. In the story of the hero he makes it clear that “the black man can recognize the absurdity of the world more rapidly than others" because he is both part of America and excluded from it by racism. Wright makes an attempt to step, beyond mere racial protests by carrying his eyes from what racism has produced to what blackness means – from the present situation which has been brought about by the past one to the present situation which is to bring about the future one. This view is confirmed by the fact that Wright made the following remark about this work in his letter to Reynolds on December 13, 1941: “It is the first time I’ve really tried to step beyond the straight black-white stuff…." (Quest, 240)

The “underground" perspective gained by Fred extends far and wide in The Outsider in its presentation of the hero, Cross Damon, who has tried to get along in the world where he can no longer find any meaning or any value. In the story he makes it more clear that the oppressed blacks are to be gifted with a “double vision" with which they are going to be both inside and outside of American culture at the same time. It is his manifestation of the serious quest for what blackness means. In the sense The Outsider is his new attempt to “achieve universality by concentrating on the specific, by dealing with his experience."

In Savage Holiday he handles with the matter of crime and guilt by portraying the white hero, Erskine Fowler, who is driven into the murder of a woman so as to disown and forget the retained image of his mother. In this work he makes a new attempt by dealing with only white characters, not black ones, in which he tries to step beyond racial protests.

In The Long Dream Wright makes a new attempt by depicting Rex Tucker who is to leave his native South for Paris. The work is written with the aim of Part One of the planned trilogy in view, in which the exile life of the hero is to be portrayed in details in non-racial circumstances.

All this taken into consideration, we conclude that Richard Wright is not a mere protest writer on racism, but a writer who has tried to step beyond racial protests by carrying his eyes from what racism has produced to what blackness means.

Notes

1 There are two editions of Uncle Tom’s Children (1938 and 1940). The former includes four short stories, “Big Boy Leaves Home," “Down by the Riverside," “Long Black Song," and “Fire and Cloud." The latter includes the four stories and “Bright and Morning Star" and “The Ethics of Living Jim Crow, an Autobiographical Sketch."

2

Lawd Today is written in the 1930’s and published posthumously in 1963.

3 “The Man Who Lived Underground" is published first in Cross Section and later included in Eight Men (1961). In 1942 two excerpts of the first draft are published in Accent under the same title.

4 Herbert Hill says in “Uncle Tom, an Enduring Myth,” in The Crisis, LXXII (May, 1965), p. 289 that an Uncle Tom is a black man who behaves without self-respect and dignity and without racial pride in relation to white persons and controlled institutions.

5 Big Boy is the hero in “Big Boy Leaves Home,” first published in The New Caravan (1936), and later included in both editions (1938 and 1940).

6 Mann is the hero in “Down by the Riverside," included in both editions.

7 Richard Wright, Uncle Tom’s Children (1940; rpt. New York: Perennial Library, 1965), p. 102; all subsequent page references to this work will appear in parentheses in this paper.

8 Sarah is the heroine in “Long Black Song," included in both editions.

9 Dan Taylor is the hero in “Fire and Cloud," first published in Story Magazine, No. 12 (March, 1938), and later included in both editions.

10 Sue is the heroine in “Blight and Morning Star," first published in New Masses, No.27 (May 10, 1938), secondly included in 1940 edition, and finally published in booklet form by International Publishers in 1941.

11 Edward Margolies, The Art of Richard Wright (Carbondale: Southern Illinois Press, 1969), P. 73. hereafter cited as Art.

12 In his autobiographical sketches “the Ethics of Living Jim Crow," first published in American Stuff (New York, 1937), and later inched in Uncle Tom’s Children (1940 edition), Wright depicts his bitter experiences in the Jim Crow South.

13 Richard Wright, Lawd Today (New York: Walker and Company, 1963), pp. 130-131; all subsequent page references to this work will appear in parentheses in this paper.

14 Katherine Fishburn, Richard Wright is Hero: The Faces of a Rebel Victim (Metuchen: The Scarecrow Press, 1977), p. 56; hereafter cited as Hero.

15 Russell Carl Brignano, Richard Wright: An Introduction to the Man and His Works (Pittsbisgh: Unversity of Pittsburgh Press, 1970), p. 25; hereafter cited as Works.

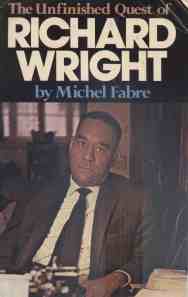

16 Michel Fabre, The Unfinished Quest of Richard Wright, tra. Isabel Barzun (New York: William Morrow, 1973), p. 155; hereafter cited as Quest.

17 Richard Wright, Native Son (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1940), p. 194; all subsequent page references to this work will appear in parentheses in this paper.

18 Bigger went to see the Daltons with his gun and knife at first, but after tie murder he did not carry them with him.

19 Saunder Redding, “The Alien Land of Richard Wright," in Soon, One Morning: New Writing by American Negroes, 1940-1962 (New York: Alfred. A. Knopf, 1963), p. 53.

20 Richard Wright, “Why I Selected 'How Bigger Was Born, '" in This Is My Best, ed. Whit Burnett (Philadelphia: Blackstone & Grayson, 1942), p. 448.

21 Constance Webb, Richard Wright: The Biography of a Major Figure in American Literature (New York: G. P. Putnum’s Sons, 1968), p. 175; hereafter cited as Webb.

22 James Nagal, “Image of 'Vision’ in Native Son," University Review, 36 (December, 1969), pp. 109-115; rpt. in Critical Essays on Richard Wright, ed. Yoshinobu Hakutani (Boston: G. K. Hall, 1982), p. 157.

23 Richard Wright, “The Man Who Lived Underground," in Cross Section, ed. Edwin Seaver (New York: Fisher, 1944), p. 58; all subsequent page references to this work will appear in parentheses in this paper.

24 Robert Felgar, Richard Wright (Boston: Twayne, 1980), p. 157.

25 Shirley Meyer, “The Identity of 'The Man Who Lived Underground, “' in Negro American Literature Forum, IV, 2 (July, 1970), p. 52; hereafter cited as “Identity."

26 Richard Wright, White Man Listen! (1957; rpt. New York: Anchor, 1964), p. 16.

27 Herbert Hill, ed., “Introduction," in Soon, One Morning: New Writing American Negroes, 1940-1960 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1963), p. 8

28 Richard Wright, The Outsider (1953; rpt. New York and Evanston: Perennial Library, 1965), p.289; all subsequent page references to this work will appears in parentheses in this paper.

29 Granville Hicks, “The Portrait of a Man Searching," New York Times Book Review (March 22, 1953), pp. 1, 35; rpt. in Richard Wright: The Critical Reception, ed. John M. Reilly (n.p.: Burt Franklin, 1978), p. 198.

30 Michel Fabre, “Richard Wright, French Existentialism, and The Outsider," in Critical Essays, p. 185.

31 Richard Wright, Savage Holiday (1954; rpt. New Jersey: Chatham, 1975), p. 30; all subsequent page references to this work will appear in parentheses in this paper.

32 Richard Wright, The Long Dream (1958; rpt. Chatham: The Chatham Bookseller, 1969), p. 145; all subsequent page references to this work will appear in parentheses in this paper.

33 Richard Wright, 'Blueprint far Negro Writing," New Challenge, II (Fall, 1937), pp. 53-65; rpt. in Richard Wright Reader, ed. E. Wright & M. Fabre (New York: Harper & Row, 1978), p. 44.

34 Felgar, p. 98.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Wright, Richard. Uncle Tom’s Children. 1940; rpt. New York: Harper & Row (Perennial Library edition), 1965.

———-. Native Son. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1940.

———-. “The Man Who Lived Underground." In Cross Section. Ed. Edwin Seaver. New York: L. B. Fisher, 1944, pp. 58-102.

———-. The Outsider. 1953; rpt. New York and Evanston: Harper & Row (Perennial Library edition), 1965.

———-. Savage Holiday. 1954; rpt. Chatham: The Chatham Bookseller, 1975.

———-. The Long Dream. 1958; rpt. Chatham: The Chatham Bookseller, 1969.

———. Eight Men. 1961; rpt. New York: World (Pyramid Books edition), 1970.

———-. Lawd Today. New York: Walker and Company, 1963.

———-. “Five Episodes." In Soon, One Morning. Ed. Herbert Hill. New York: Knopf, 1963.

———-. “The Ethics of Living Jim Crow, an Autobiographical Sketch." In American Stuff (Federal Writers’ Project anthology), New York, 1937, pp. 39-52. Rpt. in Uncle Tom’s Children. 1940; rpt. New York: Hamper & Row (Perennial Library edition), 1965, pp. 3-15.

———-. “Blueprint for Negro Writing." New Challenge, II (Fall, 1937), pp. 53-65. Rpt. in Richard Wright Reader. Ed. Ellen Wright and Michel Fabre. New York: Harper & Row, 1978, pp. 36-49.

———-. “How 'Bigger’ Was Born." Saturday Review. No. 22 (June 1, 1940), pp. 4-5, 17-20, Rpt. in Native Son. Richard Wright. New York: Harper & Row, 1965, pp. vii-xxxiv.

———-. Twelve Million Black Voices: A Folk History of the Negro in the United States. 1940; rpt. New York: Arno & The New York Times, 1969.

———-. Black Boy. New York; Harper & Brothers, 1945.

———-. “Early Days in Chicago." In Cross Section. Ed. Edwin Seaver. New York: L. B. Fisher, 1945, pp. 306-342.

———-. White Man, Listen! 1957; rpt. New York: Doubleday (Anchor Books edition), 1964.

———-. American Hunger. New York: Harper & Row, 1977.

———-. Richard Wright Reader. Ed. Ellen Wright and Michel Fabre. New York: Harper & Row, 1978.

Secondary Sources

Foreign Sources

Bakish, David. Richard Wright. New York: Frederick Ungar, 1973.

Baldwin, James. Nobody Knows My Name. New York: Dell, 1967.

———-. Notes of a Native San. New York: Bantam, 1968.

Bone, Robert A. The Negro Novel in America. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1958.

———-. Richard Wright. Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Pamphlets on American Writers (No. 74), 1969.

Brignano, Russell Carl. Richard Wright: An Introduction to the Man and His Works. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1970.

Crossman, Richard, ed. The God That Failed. New York: Harper & Row, 1963.

Fabre, Michel. The Unfinished Quest of Richard Wright. Trans. Isabel Barzun. New York: William Morrow, 1973.

———-. “French Existentialism, and The Outsider." In Critical Essays on Richard Wright. Ed. Yoshinobu Hakutani. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1982, pp. 182-198.

Felgar, Robert. Richard Wright. Boston: Twayne, 1980.

Fishburn, Katherine S. “The Long Dream." In Richard Wright: Impressions and Perspectives. Ed. David Ray and Robert M. Farnsworth. N.p.: The University of Michigan Press, 1973, pp. 174-182.

———-. Richard Wright’s Hero: The Faces of a Rebel-Victim. Metuchen: The Scarecrow Press, 1977.

Ford, Nick A. “A Long Way from Home." Phylon, XIX (Fourth Quarter, 1958), pp. 435-436. Rpt. in Richard Wright: The Critical Reception. Ed. John M. Reilly. N.p.: Burt Franklin, 1978, pp. 335-356.

———-. “The Fire Next Time?: A Critical Survey of Belles Letters by and About Negroes in 1963." Phylon, XXVI (Second Quarter, 1964), pp. 129-130. Rpt. in Richard Wright: The Critical Reception. Ed. John M. Reilly. N.p.: Burt Franklin, 1978, pp. 367-368

Gayle, Addison: Richard Wright: Ordeal of a Native Son. New York: Doubleday, 1980.

Gibson, Donald B. Ed. Five Black Writers: Essays on Wright, Ellison, Baldwin, Hughes and ReRoi Jones. New York: New York University Press, 1970.

Hicks, Granville. “Richard Wright’s Prize Novel." New Masses, 27 (March 29, 1938), p. 23. Rpt. in Richard Wright: The Critical Reception. Ed. John M. Reilly. N.p.: Burt Franklin, 1978, pp. 7-8.

———-. “The Portrait of a Man Searching." New York Times Book Review (March 22, 1953), pp. 1, 35. Rpt. in Richard Wright: The Critical Reception. Ed. John M. Reilly. N.p.: Burt Franklin, 1978, pp. 198-201.

———-. " The Power of Richard Wright." Saturday Review, 41 (October 18, 1958), pp. 13, 65. Rpt. in Richard Wright: The Critical Reception. Ed. John M. Reilly. N.p.: Burt Franklin, 1978, pp. 363-365.

Hill, Herbert. “Introduction." In Soon, One Morning. Ed. Herbert Hill. New York: Knopf, 1963, pp. 3-18.

———-. “Uncle Tom, an Enduring American Myth." The Crisis, LXXII, 5 (May, 1965), pp. 289-295, 325.

Kinnamon, Keneth. The Emergence of Richard Wright: A Study in Literature and Society. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1972.

——— “Native Son: The Personal, Social, and Political Background." In Critical Essays on Richard Wright. Ed. Yoshinobu Hakutani. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1982 pp. 120-127.

Leary Lewis. “Lawd Today: Notes on Richard Wright’s First/Last Novel." CLA Journal, XV, 4 (June, 1972), pp.411-420. Rpt. in Critical Essays on Richard Wright. Ed. Yoshinobu Hakutani. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1982, pp. 159-166.

Margolies, Edward. The Art of Richard Wright. Cardondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1969.

McCall, Dan. The Example of Richard Wright. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1969.

Meyer, Shirley. “The Identity of 'The Man Who Lived Underground.'" Negro American Literature Forum, IV, 2 (July, 1970), pp. 52-55.

Nagal, James. “Images of 'Vision’ in Native Son." University Review, 36 December, 1969), pp.109-115. Rpt. in Critical Essays on Richard Wright. Ed. Yoshinobu Hakutani. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1982, pp. 151-158.

Redding, Saunder. “The Alien Land of Richard Wright." In Soon, One Morning. Ed. Herbert Hill. New York: Knopf, 1963, pp. 50-59.

Stowe, Harriet Beecher. Uncle Tom’s Cabin. 1852; rpt. New York: F. M. Dent & Sons (Everyman’s Library edition), 1979.