概要

1985年の「リチャード・ライトと『ブラック・パワー』」の英語訳です。

写真Memoirs of the Osaka Institute of Technology, Series B, Vol. 31, No. 1: 37-48

85年にライトのシンポジウムに参加して以来、英語を使う人との遣り取りも増えたうえ、伯谷さんからは87年の年末にサンフランシスコで開かれるMLA (Modern Language Association of America) に誘われていました。書いたものを読んでもらうのに英語訳の必要性を感じていたのだと思います。

伯谷さん写真

結果的には、この作品がアフリカへのきっかけになりました。当初、ライトについての発表でお誘いを受けたMLAでは、English Literature Other than British and American の部会で、アレックス・ラ・グーマについて発表することになりました。

MLA写真

最初の誘いの言葉は、玉田さん、サンフランシスコは日本から一番近いし、ご家族一緒に来られませんか、でした。そうですね、とは答えたものの、よく考えてみましたら、発表する相手はすべて英語を話す人たちで、それからえらいこっちゃ、となりました。

サンフランシスコへは家族で行きましたが、長男は5歳、乗ってみて初めてわかったのですが、飛行機に大層弱く、行き帰りハワイを経由しても、難行苦行の空の上でした。

真冬に大阪を発ち、翌朝のハワイは常夏、しばらく夏を過ごして着いたサンフランシスコは秋の気候、帰りもその逆を経験し、体がびっくりしたと思います。

ハワイ写真

サンフランシスコ写真

4歳上の長女はその時のことを覚えているようですが、長男は何も覚えていないそうです。

92年には、今度は4人で、ジンバブエのハラレに行きました。ソウル経由でロンドンへ、そこで10日間過ごしてハラレに、帰りはパリに1週間滞在してから直通で日本に帰って来ました。長い長い空の旅でした。

ハラレ写真

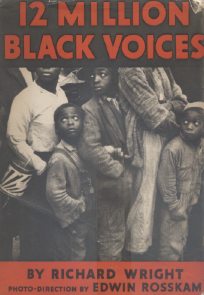

Black Power写真

本文

Abstract

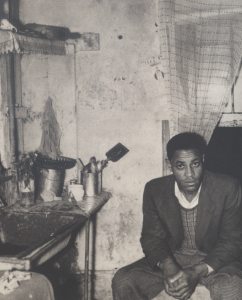

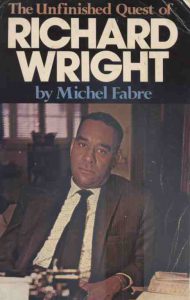

ライト写真

This paper aims to give an evaluation of Richard Wright and Black Power and to include his sharp observations and useful commentaries about Africa which now even in this modern age are still relevant.

In 1953 he made a visit to the Gold Coast, then a British colony on its way as the first black African nation towards independence from Britain. At that time a “three-sided" struggle was being fought there, made up of reactionary intellectuals and chiefs, the British Government and the politically awakened masses. As Wright was anxious to present a truer picture of the coming independent nation “Ghana" and the people’s daily lives to the world, it was essential for him to grasp how the “three-sided" struggle was being fought. He succeeded in arranging the materials he had collected and inserted his commentaries in a letter to Nkrumah that appeared at the end of the book.

In this paper efforts are made to attempt an analysis of how Wright grasped the reality of the Gold Coast, focusing on the “three-sided" struggle.

1. For Africa

Richard Wright (1908-1960) left Liverpool for Africa on the morning of June 4th, 1953. His destination was the Gold Coast, then a British colony, which was to become an independent nation under the new name of Ghana on March 6th, 1957. His “long dream" of traveling to Africa was realized with the aid of George Padmore (1902-1959), a Jamaican Pan-Africanist, with whom he had been close friends since 1946. The three-month journey was to be his first and last travel in Africa. His book about this trip was published by Harper & Brothers under the title of Black Power on September 22nd, 1954.

In Europe the book was generally accepted equanimously in most countries and especially warmly in Germany, and translated into many languages. But in England and France, however, a few publishers rejected to accept his manuscript.1

In the United States the majority of reviewers were complimentary as was shown in the case of a review which stated, “As it is a first class job and gives the best picture I’ve seen of an extraordinary situation…,"2 but there were some critical and hostile attacks which hurt his feelings bitterly.

These reactions were closely related to the various countries’ policies or interests towards the colonies. It is not difficult to conclude that the rejection of its publication in England was inextricably bound to the situation of her economy, at that time highly dependent on her colonies.

Contrary to his agent’s and publisher’s enthusiasm for publication, the book did not sell well. Although from this point of view it might be concluded that the publication was not successful, it must be remembered that some vital points, summed up in his letter to Kwame Nkrumah, are discussed in Black Power. In the letter his penetrating observations and commentaries on the coming neo-colonialism by imperialist powers are revealed to us. Undoubtedly some grave and controversial problems are posed in Black Power. But in Japan however, very few fair estimations have been made on this work so far. This paper therefore, is aimed at giving a fair assessment of Richard Wright and Black Power, including his useful foresight and warnings about Africa, which still even in this modern age, have relevance.

2. Black Power

Andre Gide (1869-1951), a member of the Investigation Committee of Colonial Problems, once made a visit to the French Congo and after the journey published Voyage au Congo, 1927. His trip was at first motivated by his curiosity for natural science, but the sight of the miserable native Africans oppressed by colonial policies and corrupt public officials, traders, and missionaries urged him to say, “I have to make a public disclosure of the real conditions" and led him to write the book.

Wright’s visit to Africa, however, was motivated in a different way. From the start he wanted to stand on African soil and introduce the daily lives of people living on the Gold Coast to the world. The Gold Coast was at that time making its way towards independence from Britain, the first black African nation to do so.

On his first day in the Gold Coast, Wright saw black men operating cranes and other machines. He remembered Dr. Malan of South Africa “had sworn that black men were incapable of doing these things."3 Thus the negative views held by Westerners confronted him as soon as he landed on African soil. It is remarkable indeed that he was unaffected by these negative views and could strive to grasp the reality of Africa itself. During his stay he undertook ventures of great risk, although he felt discouraged when he found himself regarded by the Africans as a Westerner, rather than as a descendent of a common ancestor. By his positiveness he shows us his fixed determination to make this meaningful and his determined attitude to answer oppressors through his writings.

One reviewer says, “….Simply stated, more than 300 pages are devoted to a plain narrative of Wright’s several months’ wanderings through the Gold Coast. This is no academic treatise; no effort is made to give a logical pattern to the material presented. Rather these are just a multitude of impressions…,"4 but careful reading of the text shows this to be untrue. He was prudent enough to make preparations for the journey. He had read several books on the Gold Coast and Africa listed by Padmore. Furthermore Padmore had given him another list with the names of the proper people to talk to in the Gold Coast. Consequently he was able to meet many influential people. We discover that he possessed a definite aim from the beginning of his trip when we read The Autobiography of Kwame

Nkrumah. In his book Nkrumah wrote about the birth of the Convention People’s Party. Since his returning to the Gold Coast in 1947, he had been making every effort for his native land as a secretary of the United Gold Coast Convention. He finally made up his mind to resign from the post when he was called by active supporters to lead the Convention People’s Party. The passage says:

Standing before my supporters I pledged myself, my very life blood, if need be, to the cause of Ghana.

This marked the final parting of the ways to right and left of Gold Coast nationalism; from the system of indirect rule promulgated by British imperialism to the new political awareness of the people. From now on the struggle was to be three-sided, made up by the reactionary intellectuals and chiefs, the British Government and the politically awakened masses with their slogan of “Self- Government Now."5 (Emphases mine.)

When Wright set foot on the Gold Coast in 1953, they had already started fighting this fierce “three-sided" struggle for independence. As he was anxious to present a truer picture of the coming independent nation “Ghana" and their daily lives to the world, especially to the Western world, it was indispensable for Wright to grasp how the “three-sided" struggle was being fought there. He certainly did not devote “more than 300 pages" to “a plain narrative of Wright’s several months’ wanderings through the Gold Coast." He made an effort “to give a logical pattern" by putting into collected form the notes he had acquired and declaring opinions in his letter to Nkrumah. In other words, he arranged the materials and made observations with the intention of condensing his commentaries in his letter to Nkrumah which was inserted at the end of the book. Now, let us read the text and see how Wright grasped the reality of the Gold Coast, focusing on the “three-sided" struggle.

The “British Government"

In the beginning of the letter, Wright wrote to Nkrumah, with an emphasis laid upon the psychological aspect, that confidence should be established at the center of the African personality although Westerners were intent on criticizing Africa in defense of their subjugation of Africa. And at the end of the letter he repeated that none but Africans could perform the “job" for Africa. First of all, he laid greater stress on mental “Africanization" than on anything else. It was mainly because he keenly felt distrust which was shown by every African, from the Prime Minister down to the humblest “mammy." Here is his sharp observation, an observation which can be made only by a man of great sensitivity. Putting great value on emotion and recalling Nkrumah’s having told him that missionaries had been his first political adversaries, Wright continues in the text as follows:

The gold can be replaced; the timber can grow again, but there is no power on earth that can rebuild the mental habits and restore that former vision that once gave significance to the lives of these people. Nothing can give back to them that pride in themselves, that capacity to make decisions, that organic view of existence that made them want to live on this earth and derive from that living a sweet even if sad meaning. Today the ruins of their former culture, no matter how cruel and barbarous it may seem to us, are reflected in timidity, hesitancy, and bewilderment. Eroded personalities loom here for those who have psychological eyes to see. (153)

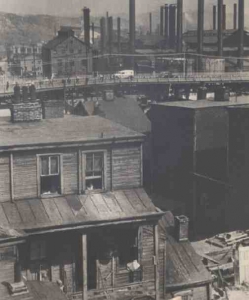

He must have wanted to emphasize that the work of the missionaries was the greatest crime that had been committed against the African people, for they had “waded in and wrecked an entire philosophy of existence of a people without replacing it, without even knowing really what they had been doing." He laid an emphasis on the psychological problem of the African people because he actually felt its necessity when he saw with his own eyes the African reality – streets without sidewalks, a drainage ditch in which urine ran, most people spitting all the time, a girl squatting over a drainage and urinating, a crowd of men, women, and children bathing themselves around an outdoor hydrant, deformed beggars with monstrously swollen legs, running sores, limbs broken, blind men whose empty eye-sockets yawned wetly, children whose entire heads were gripped with sores, mails which were not delivered because of illiteracy, a soft mound of wet rust seen here and there, lagoons with awful stench and stagnant water, causing typhoid and yellow fever and malaria, the tsetse fly, tiny mud villages filled with leprosy, still-existing human sacrifices, African workers preferring their native witch doctors to modern medical treatment, dirt highways whose accident rate was appalling, stevedores toiling with low wages like machines in inhuman conditions, poor educational systems.Those miserable conditions remind us of the following passage of Nrumah’s Africa Must Unite, in which he depicted the misery of African village life in his youth:

In all the years that the British colonial office administered this country, hardly any serious rural water development was carried out. What this means is not easy to convey to readers who take for granted that they have only to turn on a tap to get an immediate supply of good drinking water. This, if it had occurred to our rural communities, would have been their idea of heaven. They would have been grateful for a single village well or standpipe.

As it was, after a hard day’s work in the hot and humid fields, men and women would return to their village and then have to tramp for as long as two hours with a pail or pot in which, at the end of their outward journey, they would be lucky to collect some brackish germ-filled water from what may perhaps have been little more than a swamp. Then there was the long journey back. Four hours a day for an inadequate supply of water for washing and drinking, water for the most part disease-ridden!

This picture was true for almost the whole country….6

He felt stunned by what he found, but formed a clear view of the situation, and never averted his eyes from the reality wrought by the British Government. He knew well enough that both distrust peculiar to Africans and their devastating reality were only the product of colonialism which enabled colonialists to defend their financial interests. He also noticed the limitations of colonial powers which had to make the best use of traditional rural communities to rule over Africans. In his letter to Nkrumah, Wright advised him to take advantage of these limitations and said:

…And, though the cultural traditions of the people have been shattered by European business and religious interests, they were so negatively shattered that the hunger to create a Weltanshauung is still there, virginal and unimpaired. (344)

Native Africans had established their rural communities of their own accord to survive in harsh living conditions. Therefore the communities had naturally possessed the possibilities of development before the Europeans arrived. The possibilities were prevented first by the slave trade and then by such colonial policies as land exploitation, compulsory labor, taxes and so forth. During his trip Wright had a chance to see the stevedores in Accra, the miners in Bibiani and the workers of timber plants in Samreboi. They were all seasonal laborers who were forced to leave their native villages by heavy taxes and severe compulsory labor. In spite of the very low wages and dangerous work, there were enough workers. In Accra harbor, in fact, a crowd of half-nude men huddled before a wooden stairway leading up to an office, looking for a job.

Because of the slave trade and the colonial policies, the rural communities were deprived of their supporters. This deprivation prevented the possibility of development of the communities and forced them to remain weaken and undeveloped. Even in such bad conditions the African people held out against imperialist exploitation and kept up their communities with stronger solidarity and unwearying labor. Wright must have felt their “hunger to create a Weltanschauung" while he was visiting the rural communities and communicating with native Africans.

The communities were forced to change so that the British Government could rule over them advantageously. The British then gradually created distrust in the hearts of the people and brought misery to their daily lives. There was “tribalism," the communities stripped of all their supporters. We must remember that both “tribe" and “tribalism" are words of Western origin, not African. It must be also remembered that the traditional communities were reduced to mere shells by an external factor – colonial policies, and that the historical development had nothing to do with it. This is the reason why Wright advised Nkrumah to overcome “the stagnancy of tribalism" time and again in his letter to him. He knew well that the communities did not properly fulfill their functions.

In the letter to Nkrumah, Wright also advised him not to rely on the help of Western powers. He foretold that the Westerners would “pounce at any time upon Africa," given the opportunity, just as they had done in the past. History tells us that his prophecy was true. Several times Nkrumah narrowly escaped being assassinated and his Government was, in fact, overthrown by a coup d’etat. Nkrumah must have grasped the situation more clearly than any one else. It is shown in the next symbolical passage in his autobiography, in which he wrote about the time of the birth of the new nation:

As a heritage, it was stark and daunting, and seemed to be summed up in the symbolic bareness which met me and my colleagues when we officially moved into Christianborg Castle, formerly the official residence of the British governor. Making our tour through room after room, we were struck by the general emptiness. Except for an occasional piece of furniture, there was absolutely nothing to indicate that only a few days before people had lived and worked there. Not a rag, not a book was to be found; not a piece of paper; not a single reminder that for very many years the colonial administration had had its center there.

That complete denudation seemed like a line drawn across our continuity. It was as though there had been a definite intention to cut off all links between the past and present which could help us in finding our bearings. It was a covert reminder that, having ourselves rejected that past, it was for us to make our future alone.7

The “reactionary intellectuals and chiefs"

The African continent was too large and wide to be occupied completely by Westerners, therefore colonial policies were necessary. The colonial policies deprived the communities of their supporters and gave no opportunities of education to native Africans. The Westerners made the best use of the traditional rural communities to make up for their lack of people, by making a puppet of the chiefs who were still powerful over their people.

In Accra, Wright went as far as renting a car and hiring an African chauffeur, and set out undauntedly on a tour to Kumasi. His first aim was to meet and communicate with chiefs. Fortunately he was able to encounter some of them. One of them was simple-minded enough to say with deep conviction that he had an army of bees in a boy to protect him. He was also ignorant enough to intone, “We are many, many, many, " when asked how many people were in his town. These were the chiefs who were once shameless enough to sell their people to the white men in return for a bottle of gin! In the letter Wright called them “those parasitic chiefs who have too long bled and misled a naive people."

Most of the chiefs, however, were sensible enough to adjust themselves to the new situation after the Party had clipped their political wings. They were willing to pay a visit to the headquarters of the Party, to seek help in their party work, and to offer themselves to be assigned to duties. At one time the Asantehene, the most powerful chief, was about to be taken advantage of by the British Government which feared that the Gold Coast might become stronger by the centralization of administrative power. However the Asantehene eventually gave way to Nkrumah, as did the rest of the chiefs.

The bitterest political opponents to Nkrumah were the Western-educated black intellectuals, the leaders of the United Gold Coast Convention, with whom he had struggled jointly for the independence. Wright met the two important leaders of the opposition, Drs. Busia and Danquah. They were actually against Nkrumah and criticized that Nkrumah stole power and “made a filthy deal with the British." With the slogan of “full Self-Government within the shortest possible time," they had raised the nostalgic but futile cry: 'Preserve our tradition!"' On the contrary Nkrumah wrote about the opponents as follows:

The opposition in Ghana cannot boast this same sense of responsibility and maturity. So far it has been mostly destructive. We have seen the historic reasons for this in the revolution of the United Gold Coast Convention leaders from the mass movement I had achieved as their secretary, and the subsequent formation of the Convention People’s Party to embrace that mass movement as the instrument for the achievement of freedom. The U. G. C. C. leaders never forgave me and my associates for proving the rightness of our policy of 'Self-Government Now’ in the results of the 1951 election. Thereafter their opposition amounted to a virtual denial of independence and a reluctance for the British to leave. They were prepared to sacrifice our national liberation if that would keep me and my colleagues out of government.8

During his stay in Africa, Wright heard a black young man complain that he could not ask the rich Africans for help because they were worse than the British. The interviews with some black intellectuals made him realize that they could not understand the real situation of the masses at all. So in his letter to Nkrumah he concluded that Nkrumah should not have the Western-educated Africans with him in his struggle for liberating the Gold Coast.

The “politically awakened masses"

The British brought about nothing but misery to their lives. The chiefs misled their people. Some of the black intellectuals were worse than the British. The masses trusted nothing and nobody. There burned in their hearts “a hunger to regain control over their lives and create a new sense of their destinies." (91) They could swear “oaths to invisible gods no longer and now at last, they were swearing an oath that related directly to their daily welfare." (60) Within a short period Nkrumah was able to hold such masses in the palm of his hand. On the situation Wright made the following remark:

…Nkrumah had moved in and filled the vacuum which the British and the missionaries had left when they had smashed the tribal culture of the people! It was so simple it was dazzling….Of course, before Nkrumah could do this, he would first have to have the intellectual daring to know that the British had created a vacuum in these people’s hearts. It was not until one could think of the imperialist actions of the British as being crimes of the highest order, that they had slain something that they could never rekindle, that one could project a new structure for the lives of these people. (60)

They hailed Nkrumah with hearty cheers on the roadsides and at the political mass meetings. Wright was thunderstruck when he saw the crowds shouting and calling: “Free―doom! Free―dooooom!" They were trade-unionists, students, “mammy" traders of the streets, and the nationalist elements who were completely ignored by the United Gold Coast Convention. The women were most enthusiastic of all, for they had put up with the coldest treatment under the colonial policies. In 1949, when Nkrumah was charged with contempt of court and fined three hundred pounds, the sum was quickly raised by the voluntary efforts of the street “mammy." Most of the masses were illiterate and did not clearly know where they were going with Nkrumah. Wright knew the situation well, so in the letter he wrote that Nkrumah should determine “the logic of his actions by the conditions of the lives of the people," and that the temporary discipline should place “the feet of the masses upon a basis of reality." And he finally drew a conclusion:

AFRICAN LIFE MUST BE MILITARIZED!

…not for war, but for peace; not for destruction, but for service; not for aggression, but for production; not for despotism, but to free minds from mumbo-jumbo. (346)

It must have been his friendliest advice to Nkrumah, for he keenly felt that the path to independence would be rough and rugged beyond imagination.

III. What Africa means in this modern age

The Western powers have done a lot of injustice to Africa and the situation is as bad as it was. Dr. Du Bois, one of the Pan-Africanists, once pointed out: “The problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color-line."9 His prophecy turned out to be true. Now under the nuclear threat, the Third World has become a significant bridge between the existing two Worlds. Undoubtedly Africa holds the key to the present situation.

A lot of things can be learned if we look at the history of Africa. The Africans lived as human beings even under the severest exploitation of the slave trade and the colonial policies. They have kept their tradition, culture, education, and so on under the worst conditions in the world, never having received the benefit of modern civilization, science and technology. Now most of the independent nations in Africa are struggling against neo-colonialism. We can not avert our eyes from their sincere struggle.

Sembene Ousmane (1923- ), a Senegalese writer, came to Japan in 1984 and said, “We need no help. We’d like you to have a fair understanding of the situation" on the hunger aid campaign, then active in Japan.10 His sharp commentary urged us to reconsider what we should do.

On the African problem Wright also made the following commentary in the text:

One does not react to Africa as Africa is, and this is because so few can react to life as life is. One reacts to Africa as one is, as one lives; one’s reaction to Africa is a vast, dingy mirror and what modern man sees in that mirror he hates and wants to destroy. He thinks, when looking into that mirror, that he is looking at black people who are inferior, but, really he is looking at himself and, unless he possesses a superb knowledge of himself, his first impulse to vindicate himself is to smash this horrible image of himself which his own soul projects out upon this Africa….

Africa is dangerous, evoking in one a total attitude toward life, calling into question the basic assumptions of existence. Africa is the world of man; if you are wild, Africa’s wild; if you are empty, so’s Africa…. (158-159)

With the friendly help of Padmore, Wright was able to visit the Gold Coast, then making its way towards independence. Consequently, he succeeded in presenting the struggle for independence of the Gold Coast and the daily lives of the Africans to the world. He deserves praise for presenting a truer picture to the world earlier than any one else. In the letter to Nkrumah, Wright wrote to him on neo-colonialism:

…You might, by borrowing money from the West, industrialize your people in a cash-and-carry system, but, in doing so, you will be but lifting them from tribal to industrial slavery, for tied to Western money is Western control, Western ideas…. Kwame, there is nothing on earth more afraid than a million dollars; and, if a million dollars means fear, a billion dollars is the quintessence of panic…. (346)

In the letter Wright also said to him on corruption:

Regarding corruption; use fire and acid and cauterize the ranks of your party of all opportunists! Now! Corruption is the one single fact that strikes dismay in the hearts of the friends of African freedom…. (349-350)

If we take into account what Ghana has become, we discover that his warnings and advice are still vital indeed.

4. Richard Wright and Black Power

In Native Son (1940) Wright depicted the black-white problem vividly through the story of Bigger Thomas who was finally driven to murder a white girl and a black girl. In the story, Wright both directed active protests against the whites and extended passive warnings towards the blacks. At the same time he portrayed his dissatisfaction with the Communist Party which could see the racial situation in general, but could not see the individual in the mass. We notice that he already started to step beyond the racial problem. By the end of 1941 when he wrote the manuscript of “The Man Who Lived Underground," he was clearly determined to step beyond the straight black-white problem. In the revised version of “The Man Who Lived Underground" (1944), he was able to handle a wider and deeper theme from a new viewpoint.

He left the Communist Party in 1944, for he had begun to reconsider the relationship between the society and the individual. By reexamining the history of the oppressed blacks in the United States, he was able to write 12 Million Black Voices (1941). Recollecting his early days, he set out to write his autobiography. It appeared as articles in “I Tried to Be a Communist" (1944), “Early Days in Chicago" (1945) and “American Hunger" (1945), and as a book in Black Boy (1945). He confessed how difficult it had been to wrestle with himself:

…I found that to tell the truth is the hardest thing on earth, harder than fighting in a war, harder than taking part in a revolution. If you try it, you will find that at times sweat will break upon you. You will find that even if you succeed in discounting the attitudes of others to you and your life, you must wrestle with yourself most of all, fight with yourself; for there will surge up in you a strong desire to alter facts, to dress up your feelings. You’ll find that there are many things that you don’t want to admit about yourself and others. As your record shapes itself an awed wonder haunts you.11

In 1946 he visited Paris and enjoyed the mood of freedom after the Second World War. In 1947 he moved to Paris with his family to start a new life. He had left his private troubles behind in the United States. In Paris he was able to see America and racial problems objectively. The viewpoint of “The Man Who Lived Underground" deepened and widened in The Outsider (1953) and Savage Holiday (1954). In the former he severely criticized Western civilization from the ideological aspect and in the latter from the psychological. In The Outsider, Cross Damon, protagonist of the story, whispers before his death to Houston, the New York District Attorney:

'I wish I had some way to give the meaning of my life to others….To make a bridge from man to man…Starting from scratch every time is…is no good. Tell them not to come down this road….Men hates themselves and it makes them hate others….We must find some way of being good to ourselves….Man is all we’ve got….I wish I could ask men to meet themselves….We’re different from what we seem….Maybe worse, maybe better…But certainly different…We’re strangers to ourselves’.12

Wright’s way of life was symbolically shown by the confession. At that time he could not anchor any hope either in America or in European countries. He was anxiously awaiting another new hope to liberate the oppressed black people and himself. In that context, the following commentary is to the point:

Actually, what Mr. Wright says is a re-statement in terms of Gold Coast problems of the fundamental argument in The Outsider: that the confusion and terror which stalk the world are in very fact a mirror reflecting the basically bestial motive in Western culture.13

It can be said that the same problems are discussed both in The Outsider and Black Power, and that “finally, in a profound way, it is a book about Wright himself."14

At the end of his trip he wrote a letter to Paul Reynolds:

I was shocked at what I found here, and yet I’m told that the Gold Coast is by far the best part of Africa. If that is so, then, I don’t want to see the worst.15

In spite of this declaration, he planned to visit some French speaking West African nations. His sudden death prevented it. However, he made desperate attempts for he regarded Africa as the important bridge between two Worlds.

We can not form a true estimation of Richard Wright and his works unless we give a fair evaluation to Black Power.

Notes

1 Michel Fabre, The Unfinished Quest of Richard Wright, tra. Isabel Barzun (New York: William Morrow, 1973), p. xx.

2 Ed. John M. Reilly, Richard Wright; The Critical Reception (N.P.: Burt Franklin, 1978), p. 254.

3 Richard Wright, Black Power (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1954), p. 33; All subsequent page references to this work will appear in parentheses in this paper.

4 Reilly, p. 265.

5 Kwame Nkrumah, The Autobiography of Kwame Nkrumah (London: Cox & Wyman, 1957), p. 89.

6 Nkrumah, Africa Must Unite (London: Panaf, 1963), p. 34.

7 Nkrumah, Africa Must Unite, p. xiv.

8 Nkrumah, Africa Must Unite, p. 69.

9 W. E. B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folks (1903; rpt. New York: Kraus-Thomson Organization, 1973), p. 40.

10 He made this commentary at the meeting held by Black Studies Association in co-operation with Black Studies Association of Ritsumeikan University in Kyoto, on March 3rd, 1984.

11 Richard Wright, “Richard Wright Describes the Birth of Black Boy," New York Post, November 20, 1944, p. B6.

12 Richard Wright, The Outsider (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1953), p. 405.

13 Reilly, p. 268.

14 Edward Margolies, The Art of Richard Wright (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1969), p. 27.

15 Fabre, pp. 399-400.

元→「リチャード・ライトと『ブラック・パワー』」

執筆年

1986年

収録・公開

Memoirs of the Osaka Institute of Technology, Series B, Vol. 31, No. 1: 37-48

ダウンロード

Richard Wright and Black Power(119KB)