Some Onomatopoeic Expressions in ‘The Man Who Lived Underground’ by Richard Wright

解説

「Richard Wright, “The Man Who Lived Underground” の擬声語表現」の英語訳です。元(日本語)→「Richard Wright, “The Man Who Lived Underground”の擬声語表現」

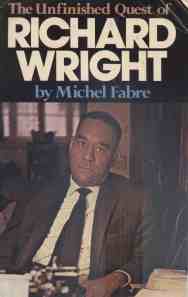

ファーブルさん (Michel Fabre) に見てもらって、自分のレベルがどの辺りにあるのかを知りたいと思い、英語訳しました。ファーブルさんはフランス人ですが、ライトの伝記を書いておられて、その本の序文を読んで「すてきなことを言う人だなあ」と思って以来、何かのきっかけでお会いしたいと考えていたのが、本当の動機かも知れません。

教員再養成の大学院でご一緒した東京の萩野浩さんの家まで押しかけて、英語を見てもらいました。二十数歳年上の英語の出来る先輩しか頼る人がいなかったからでしょうが、お忙しい中をおしかけてご無理をお願いしました。

初めてこの作品を読んだのは夜間の学生としてで、その時の講師(非常勤講師)が小林信次郎(当時大阪工業大学教授)さんでした。その後、非常勤講師として大阪工業大学でお世話になり、この文章も紀要に入れてもらって活字になりました。

振り返れば、萩野さんや小林さんなど、先輩のお世話になってばかり、人に迷惑ばかりをかけてきました。

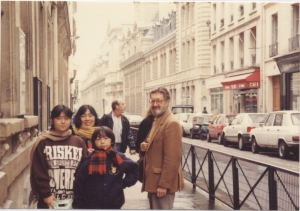

ファーブルさんとは、85年のライトの国際シンポジウムで初めてお会いし、92年にはジンバブエからの帰り道に、パリで家族と一緒に再会することになりました。その後も、ニューヨークからバズル・デヴィッドスンさんの古本を送って下さったり、お手紙を下さったりと、目にかけてもらっていますが、長い間、ご無沙汰しております。

ファーブルさん、お元気でいらっしゃいますか。

ソルボンヌを背景に家族とファーブルさん

概要(Abstract)

The aim of this paper is to form an estimation of Richard Wright’s “The Man Who Lived Underground" through analysis of some onomatopoeic expressions he skillfully used in some scenes of this “underground" story. This novel has been estimated as an excellent work. The estimations are based mainly on the excellence of the theme and his vision presented in the story. Through the realistic portrayal of the hero’s “underground" life Wright puts broader and deeper problems to us readers. The eyes of most critics, in fact, have been focused on the subject and his viewpoint. However what we cannot fail to miss is the art of his expressions that supports this story.

In this paper efforts are made to describe how Wright avoids redundancy, appeals directly to our ears, then violently beats and deeply stirs our hearts by making the skillful use of echo words, especially by making the most use of clangs and clank, the sounds of the manhole cover, closely related to the main theme.

本文:Some Onomatopoeic Expressions in “The Man Who Lived Underground" by Richard Wright

The aim of this paper is to form an estimation of Richard Wright’s “The Man Who Lived Underground" through analysis of some onomatopoeic expressions he skillfully used in some scenes of this “underground" story. In this paper onomatopoeias or echo words mean articulate sounds1 which are imitative of a particular kind of sound rather than the sound itself, and most of the words we are to refer to here are given the sign of [Imitative.] by O.E.D.

This novel has been evalued as an important landmark in Richard Wright’s world. In 1994 it was published as one of “new American writings" in the anthology Cross-Section, and

posthumously in 1961 included in his own collection Eight Men. It is remarkable that in 1956 the work was selected as one of the novels in Quintet – 5 of the World’s Greatest Short Novels, along with Aldous Huxley’s, Leo Tolstoi’s, Guy de Maupassant’s and William Saroyan’s. In 1973 Michel Fabre pointed out in his The Unfinished Quest of Richard Wright that it was the first time Wright had really tried to step beyond the straight black-white stuff, and at the same time made it clear that it was an important work which inspired quite a few black writers of the following generation like Ralph Ellison (1914 – ).

The estimations are formed on the basis of the fineness of its theme and on his vision presented in the story. Through the realistic portrayal of the hero’s “underground" life Wright poses broad and deep problems to us readers. The theme is broad and deep enough to extend beyond racial problems. His vision is enlightening enough to hint to us that oppressed blacks stand at a vantage point where they can free themselves from daily encroachments and thus see the reality of our society more clearly and more easily than others because of being excluded from it by racism. The eyes of most critics, in fact, focus too much on the subject and his viewpoint. But can we not say they miss the fact that the subject and his viewpoint are supported by his skillful expressions? Or can we not say that they pay too little attention to the skillfulness and appropriateness in his choice of words?

Wright owed the idea for the underground section to a piece in a detective magazine which was a story of a prisoner being actually held on robbery charges.2 Giving full play to his own imagination from his viewpoint, he made up his story. The hero, who is forced to flee from the police for a murder crime which he did not commit, happens to take refuge by escaping into the sewer. After various extraordinary experiences underground, he surrenders to the police to confess his guilt only to find that the real murderer has been caught. The police regard him as crazy and put an end to the matter by shooting him into the city sewer water. The story itself is gloomy and we end up feeling dissatisfied. But the novel itself never fails to hold our attention throughout the story. The way in which the story develops is so thrilling that we can enjoy reading the reverse of reality which the hero sees in the story. At the same time we cannot forget that the thrill which stirs within us is brought about by his vivid expressions of sounds and colors, his terse expressions with participial constructions or with represented speeches, his devised expressions of dreams which the hero has in the story and so on.

Of all the above devised expressions, we intend to pick out and analyse some noteworthy expressions in the following three scenes:

(1) – the unfolding scene where the hero, while fleeing from the police, happens to see a manhole cover thrown up by the sewer water, hits upon the idea of escaping underground, then puts it into practice – <DOWN INTO THE UNDERGROUND WORLD>

(2) – the scene where the hero, after his extraordinary experiences in the sewers, returns through the same manhole to ground level in order to proclaim his discovery to the world – <UPTO GROUND LEVEL AGAIN>

(3) – the final scene where the hero takes the policemen to the manhole to show his experiences underground, but is shot into the dirty sewer water – <DOWN INTO THE UNDERGROUND WORLD AGAIN>

We can see some onomatopoeic expressions in some other scenes in the story, but we pick out the three scenes here. One reason may be that echo words are used here more frequently and more effectively than in other places. Another reason may be that each scene includes the sound of the manhole cover, which is ringing over the whole story like a keynote. In the story the sound of the manhole cover is used four times – twice in the scene (1) (a noun clang and a verb clang), once in scene (2) (a noun clang) and once in scene (3) (a noun clank).

We intend to focus attention on the manhole cover or its metallic sound – clang or clank. One reason might be that the cover, in a literary sense, plays a role of separating ground-level from the underground – the ground level which is marked by chaos and disorder from the underground where the hero discovers his real-self which he cannot find in his daily life. Another reason might be that the cover symbolizes some dominant theme or other and that its sound plays an important part in appealing symbolically to the ears of the readers.

Now, let us start with the unfolding setting, focusing upon this onomatopoeic clang.

<DOWN INTO THE UNDERGROUND WORLD>・・・・・・A man, apparently the hero of this story, is hiding in a doorway, when the siren of a police car sounds. He says to himself, “I’ve got to hide…." Then a sudden movement in the street catches his attention. The story in the text goes as follows:

Then a sudden movement in the street caught his attention. A throng of tiny columns of water snaked into the air from the perforations of a manhole cover. The columns stopped abruptly, as though the perforations had clogged; a grey spout of sewer water jutted up from underground and lifted the circular metal cover, juggled it for a moment, then let it fall with a clang.

He hatched a tentative plan: he would wait until the siren sounded far off, then he would go out…3

The text shows that the manhole cover pushed up by the sewer water drops onto the street with a vigorous sound and also shows that the writer uses this clang to express the sound of the metal cover. Strictly speaking, it might be better to say that he sets this opening scene where the sound of the cover can be effectively expressed by clang. In this sense, anyway, the frictional sound produced by the cover falling on the ground is expressed by clang.

First of all, some analysis of this word is to be attempted here. Looking up in O.E.D., you will find clang signified as follows:

Clang (klAN), sb.

- A loud resonant ringing sound; orig., as in Latin, that of a trumpet, and so still in literary use ; but now, most characteristically, the ringing sound of metal when struck, as in 'the clang of arms’; sometimes also the sound of a large bell. (The underlining is mine.)

The underlined part shows us that the sound of clang is characterized by loudness. In this respect it is suggestive that Otto Jespersen points out that a great many words beginning with l-combinations are characterized by loud sounds.4

Now we should like to put some analytical interpretations upon this cl– [kl], a combination of a plosive [k] and a liquid [l]. Plosives, in most cases, denote sounds which are produced by blowing or striking something, or by impact, friction and so on. Voiceless sounds including [k] are especially characterized by lightness and clearness. Liquids including [l] are melodious and harmonious to our ears and expressed by such movements as shaking, flowing, flying, etc. rather than becoming stationary in a positive sense or of giving a feeling of velvety smoothness in a passive sense.5 These interpretations tell us that the combination cl– [kl], in this case, expresses the light, clear and metallic sound produced by the manhole cover which falls to the ground after being pushed up by the sewer water.

Next some consideration should be given to the nasal –ng [N], the ending of this word. Nasals denote the continuity of a sound and –ng, marked by the reverberation of a sound, is particularly suitable to express grumbling reverberation.6 So it might safely be said that the lingering echo is the chief note of this –ng sound while loudness is that of the cl– sound. The above considerations lead us to the conclusion that this unfolding setting could be adequately expressed by one word clang, which shows that the manhole cover falls to the ground with a clear, loud and metallic sound and also that the sound echoes with a light and clear reverberation. Paradoxically the writer sets this opening scene where clang is effectively represented as a symbol of loudness and lingering echo.

What kind of effect does the writer aim to produce on us readers by this clang? Or why does he use it in this situation? To throw some light on the matter, we must go back to the original. We have briefly touched upon the scene where the hero hiding in a doorway was surprised to hear a police car swishing by. Here is the text of the opening scene where the hero in flight happens to see a sudden movement in the street:

I’ve got to hide, he told himself. His chest heaved as he waited crouching in a dark corner of the vestibule. He was tired of running and dodging. Either he had to find a place to hide, or he had to surrender. A police car swished by through the rain, its siren rising sharply. They’re looking for me all over…. He crept to the door and squinted through the fogged plate-glass. He stiffened as the siren rose and died in the distance. Yes, he had to hide, but where? He gritted his teeth. Then a sudden movement . . . (58)

From the text we cannot see who and what he is, but at least can recognize that he, tired of running, is determined to surrender unless he finds a hiding place. We also find that he is so tense; he stiffens to hear the siren rising, thinking, “They’re looking for me all over. . . ," and that he, unable to find where to hide, is so desperate; he grits his teeth. He has indeed been driven to despair. His desperateness leads him to become reckless enough to devise a plan of escaping into the manhole where the dirty water is spewing out, and bold enough to carry out the plan by creeping out to the street where a police car is swishing past so frequently. He is full of despair, impatience and irritation, so this clang represents a sound so loud that momentarily he forgets all these feelings. He is clearly upset by being unable to find a place to hide. This is why this clang has lingering echo which gives him the illusion that the manhole cover can seduce him into the underground world.

We can see three sorts of effective devices used in this word.

(1) The writer puts the noun clang at the end of the sentence, not the verb clang, so as to produce the effect of a ringing note.

(2) He ends the sentence with clang. The lingering echo of this clang is carried over to the new paragraph, heightened by the pause between.

(3) He contrasts clang with swish of the police car.

It has been mentioned that he is made to feel impatient by the swishing sound. Now let us pay attention to this word swish. Swish is expressed in O.E.D. as follows:

Swish (swiΣ) , int. or adv. and sb.1 [Imitative.]

A. int. or adv. Expressive of the sound made by the kind of movement defined in B. 1; with a swish. Also reduplicated swish, swish.

B. sb.

1. A hissing sound like that produced by a switch or similar slender object moved rapidly through the air or an object moving swiftly in contact with water; movement accompanied by such sound.

Swish (swiΣ) , v. [Imitative. Cf. prec.]

- intr. To move with a swish (see prec. B. 1) ; to make the sound expressed by 'swish.’ (The underlining is mine.)

Looking at the underlined parts we can understand the sound of swish is distinguished by rapidness and swiftness of movement. In this case it could be said that the swiftness of the running car makes him feel more impatient. Conversely the writer uses the speeding car in this setting to make the hero feel more impatient.

Let us try to put forward more analytical interpretation. Fricatives including [s] and [S] are designed to copy sounds which are produced by creak, clash, friction and so forth. In this case [s] and [S] of this word copy the frictional sounds (shu [Sɯ] and shu’ [Sɯ’] in Japanese) which are produced by the rubber tires of a running car or a pavement moistened by rain.

Secondly the order, in which vowels symbolize loudness, lightness and distance of sounds, is : [i] < [e] < [ε] < [A] < [a] < [u] < [o] < [x] (or. . . [a:] < [x:] < [u:] ). And the vowels [i] and [i:] in particular are appropriate to symbolize what is small, weak, insignificant, swift, abrupt, etc.

Thirdly [swi] is symbolic of the abrupt change like hyo’ [çjo’], nyu’ [ɲɯ’], etc. in Japanese.

Now we could say that the one word swish expresses the abrupt movement of the police car with [swi], the swiftness and sharpness of the sound with [i], and the frictional sound produced between the movement and the wheels of the car speeding through the rain with [s] and [Σ].

The duration of the sound is naturally short because the car drives away at full speed. It is the shortness of the duration that makes an effective contrast with aloud and ringing clang, which lingers long in his ears. This shortness, indeed, makes the effect of the lingering note of this clang.

It is noticeable that we can see the similar sound combination in the closing scene of this story (clank and swish). What is more noticeable is that the same combination is also seen in the opening scene of Native Son, his previous novel, 1940. Here is the text:

Brrrrrrriiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiinng!

An alarm clock clanged in the dark and silent room. A bed spring creaked. A woman’s voice sang out impatiently:

'Bigger, shut that thing off!’

A surly grunt sounded above the tinny ring of metal. Naked feet swished dryly across the planks in the wooden floor and the clang ceased abruptly.7

The text shows that the movement of the ringing alarm clock is expressed by the verb clang and its sound by the noun clang. Can we not say that the effect of the loudness and clamorousness of clang is heightened by the contrast with the sharp, short sound of swish produced when the boy scurries over the floor to stop the clock? All this taken into account, this clang seems to symbolize the metallic ring by which the curtain virtually rises on the “underground drama" as well as the echo which seduces the hero into the underground world.

The man, hitting upon a tentative plan of hiding in the sewer, waits for the chance to carry it out. He steps to the manhole and peers into the sewer. Then as the siren of a police car rises again, with a wild gasp of exertion, he lets his body sink into the sewer water through the manhole, grasping the metal prongs, fist over fist. He hears a scream of brakes and sees a white face looming above him. The original reads like this:

'How did this damn thing get off?’ he heard a policeman asked.8 He saw the steel cover move slowly until the whole looked like a quarter moon turned black. 'Give me a hand here,’ someone asked. The cover clanged into place, muffling the sights and sounds of the upper world. (59)

From the text we learn that the sound, made by the manhole cover when replaced, echoes loudly again, but this clang seems to sound somewhat different from the previous noun clang. There are two reasons. One reason is that this time he hears the sound underground while he previously heard it aboveground. The other is that this sound is made by the policeman when he replaces the cover while the previous sound was produced by the sewer water when the cover was dropped on to the ground. Judging from their conversation, one of them must have put it into place, muttering disgustedly to himself, “This damn thing!" Perhaps the writer dares to use the verb clang in this passage with the intention of laying emphasis on the action of the policeman. This feeling of disgust combines with the ringing note of the manhole cover, so the combined sound in the sewer must have rung bitterly and lingeringly to his ears. This clang has a metallic ring which announces the beginning of this underground life while the other clang had a ring of seduction into the underground world. It is quite ironical that the sound is produced by one of the policemen who have driven the hero into the underground.

It is the swish of the police car as described earlier that has made him feel more impatient. It is also the siren of the police car that has forced him into the underground. Let us go back to the original to look at the details. When he peers into the manhole, he hears the siren rising. The passage reads in the text: “The siren seemed to hoot directly above him," which shows hoot is used to express the sound. This hoot includes a vowel [u:] and a plosive [t]. [u:] is symbolic of what is darker, farther, bigger, etc. than any other vowel, and [t] is appropriate to express the sudden, abrupt movement. [u:] conveys the impression that the siren is coming nearer to him, becoming louder and louder, and from [t] we gain the impression that the sound has penetrated his ears abruptly and sharply. In this word there is a strong indication that the sound has urged the hero to make a move but that he is still hesitating to take further action. What interests us is that the high back vowel [u:] of this hoot makes a striking contrast with the high front vowel [i] of swish. It seems that [swiS] and [hu:t] are caught by his ears, mingled with each other, and that he is threatened by the mingled sounds, immediate and remote, large and small, or sharp and dull.

The siren [hu:t], in an instant, makes him put his hands on the rim of the manhole, then lower himself into the watery darkness. In the darkness the siren seems to sound to his ears in a different way. This is learned from the text: “… the siren seemed to howl at the very rim of the manhole," which shows that the writer replaces hoot with howl. In this sentence [haul], generally denoting the sound produced by animate things, is used to express the personified sound of the police car. It seems as if a dog, in chase, were furiously barking at the mouth of the hole, and on the point of leaping down onto the hero in flight. This howl, we could say, speaks so eloquently of the mentality of the pursuer and the pursued.

He releases his hold on the prongs as if he were urged by the howling siren. He drops and is swept violently into leaping sewer water. By clawing frenziedly at a crevice, he has a narrow escape from death and steadies himself in the swift current. Then the sound of brakes comes to his ears. The passage in the text reads “He heard a prolonged scream of brakes and the siren broke off. Oh, God! They had found him!" (59) Speaking of scream – the sound of brakes, the frictional movement of the wheels is indicated by [skr], the immediate, sharp ring of its sound by [i:], and the continuous, lingering note of it by the nasal [m]. The policeman, having seen the manhole cover discarded in the middle of the street, must have put on his brakes sharply. The car stops abruptly, giving forth a sharp and lingering sound in their ears. Such a scene is vividly expressed by one word – scream.

Then the above-mentioned scene is moved to where the cover is put into place by the policeman. The sound of the upper world, muffled by the cover, seems to come to his ears quite differently from what he had heard before as the next passage shows:

…His lips parted as a car swept past along the wet pavement overhead, its heavy rumble soon dying out, like the hum of a plane speeding through a dense cloud. He had never thought that cars could sound like that; everything seemed strange and unreal under here. He stood in darkness for a long time, knee-deep in rustling water, musing. (59)

The sound of the car rumble shows the flowing movement with the liquids [r] and [l], the frictional noise produced between the tires and the pavement with the voiced plosive [b], and the continuous echo with the nasal [m]. It is compared to [hVm] of a plane speeding through a dense cloud. To put it the other way around, they sound strange enough for the hero in the current of the sewer to take them for the rumbling of the plane. This rumble, the combination of voiced sounds, makes a contrast with the four words, swish, hoot, howl and scream, each of them having one or two voiceless consonants. This might be the writer’s device; [rVmbl] and [rVsl], having two liquid consonants (r and l), show a striking contrast between the voiced [mb] and the voiceless [s] and the contrast makes us notice the difference between the remote, dull and noisy sounds aboveground and the immediate, clear and agreeable ones underground. It is remarkable that the combination of rumble and rustle brings out the contrast between them as that of swish and clang did.

Next comes the scene where he peers into the hole for the first time, which is described in the text as “He went to the center of the street and stooped and peered into the hole, but could see nothing. Water rustled in the black depths." (58) It shows that the flowing of the sewer water becomes rustle again, which contrasts with a series of swish, hoot, howl, scream and rumble. When we notice the contrasting sound between them, the din and bustle of human society aboveground seem to sound more harsh and disagreeable to our ears than before. We also find ourselves seduced into the “underground world" as we see a clear picture of the hero standing musing in the sewer where darkness and stillness reign as the manhole cover muffles the sights and sounds of the upper world. Observe the writer’s device ; both clang and rustle are not only inserted among the variedly expressed words but used in two proper ways – the former is used as a verb and a noun while the latter a noun and an adjective.

<UPTO GROUND LEVEL AGAIN> – He finds his identity while he is groping through the sewers and observing the reverse of reality of the upper world from a vantage point where he is not being seen by others. Then he makes up his mind to climb up again to ground level and returns to the same manhole compelled by his new discovery to make a statement to the world. Catching hold of the steel hooks, he hoists himself up, puts his shoulder under the cover, and moves it an inch. Then comes the following passage:

A crash of sound came to him as he looked into a hot glare of sunshine through which blurred shapes moved. . . . A heavy car rumbled past overhead, jarring the pavement, warning him to stay in his world of dark light, knocking the cover back into place with an imperious clang. (88-89)

Crash presents a great contrast to the stillness which has long reigned underground. Now let us go back to O.E.D. once again. Crash is thus described in it as:

Crash (krAS), sb.1 [f. CRASH v.]

- The loud and sudden sound as of a hard body or number of bodies broken by violent percussion, as by being dashed to the ground or against each other; also transferred to the sound of thunder, loud music, etc. (It is often impossible to separate the sound from the action as exemplified in sense 2.)

- The breaking to pieces of any heavy hard body or bodies by violent percussion; the shock of such bodies striking and smashing each other. (The underlining is mine.)

Loudness and suddenness, as are shown in the underlined parts, mark the sound. In this case the plosive [k] and the fricative [S] included in this word seem to have a loud and sudden note which breaks the profound stillness of the sewers with one blow. When he hears the sounds of the upper world again, he drops back into the dirty current, overwhelmed by the crash. From the text we know they are also a combination of voiced sounds, rumble and jar, which are imitative of the indirect sounds muffled by the metal cover. We notice that to his ears the sounds of the upper world are noisy and dull enough to contrast with the silence underground because jar is distinguished by harshness or in- harmoniousness. In this sense crash is also playing a role of telling the difference between the sounds, aboveground and underground. The following device the writer uses tells how terrific clang sounds to his ears; he puts this noun clang with the preposition with at the end of the paragraph as is also the case of the first clang. When he hears the metallic clang above him, he must have thought that they were sounding an “imperious" warning against him, “Never come back again to the world."

<DOWN INTO THE UNDERGROUND WORLD AGAIN> – He finally succeeds in returning to the ground above. After a while, by irony of fate, together with the very policeman that drove him into the sewers, he comes back again to the same manhole so as to tell what he has seen underground. The story ends ironically, however, as he is shot down into the dirty city sewer by one of them as if he were mere trash. The text of the closing scene reads as follows:

As though in a deep dream, he heard a metallic clank; they had replaced the manhole cover, shutting out forever the sound of wind and rain. From overhead came the muffled roar of a powerful motor and the swish of a speeding car. (101-102)

We mentioned that each of the last three clangs had the ending –ng with some ringing note which symbolized something full of implications. This clank, in place of clang, has the ending –nk including the plosive [k], which is suitable to denote sounds of sudden, instantaneous movement with no lingering note. We find that the cover has made a very loud sound indeed because this word includes cl-, symbolic of loudness, but why does the loud metallic sound have no lingering echo inside the manhole? It is because the policeman puts it into place very gently on purpose for fear of making a noise. Then why does he replace so gently while he replaced so aggressively before? The real reason for his furtive behavior is to be found in the guilty conscience he feels. Now that they have caught the real murderer, they have no need to arrest this man who has surrendered himself to the police. The man, who now speaks of his underground life, appears to them a trouble-maker, because the truth is that they trapped him by a trick into making a false confession, then let him sign his name to the confession. At last one of them is determined to put an end to the matter before their unlawful deeds are exposed to the public eye. Led by the man, he arrives at the manhole. He finally settles the matter by shooting him to death, but begins to have a guilty conscience. When asked by one of his fellow officers why he shot the man, he explains, hiding behind police authority, “You’ve got to shoot his kind. They’d wreck things." But he cannot yet free himself from the guilty conscience. So he hushes the “crying baby" to sleep forever by putting the cover into place as gently as possible.

The final interpretation is to be put on roar and swish, expressive of the sound of the upper world. The O.E.D. expresses it this way:

Roar (rōəɹ), sb. 1

- A full, deep, prolonged cry uttered by a lion or other large beast; a loud and deep sound uttered by one or more persons, esp. as an expression of pain or anger.

- transf. The loud sound of cannon, thunder, a storm, the sea, or other inanimate agents.

Roar, characterized by loudness, is doubled in tone by swish which stands out in sharp contrast to it. The mixture of the loud roar and the sharp swish must have reached the ears of the hero who is now being washed away with the debris into a bottomless pit. When he hears roar, which is heightened by the effect of swish, he must have felt, falling senseless, as if someone uttered a full, deep, prolonged cry in pain or anger as is shown in the signification 1 in O.E.D. Certainly swish sets off clank to advantage as is the case of the combination of swish and clang in the opening scene. We already mentioned the first clang carried a suggestion of seduction into the sewer; the second clang that of the beginning of his underground life; the third clang that of the warning from the upper world. This final instantaneous clang with no ringing notes, to be sure, symbolizes his collapse which has been brought about because he could not make himself understood by the world. The story, indeed, opens with the combination of swish and clang and ends with that of clank and swish.

Onomatopoeic words are widely spread throughout our daily conversations, nursery words, slangs, dialects, etc. and especially in recent years through comic strips, but are not necessarily established as regular forms. In this work, however, onomatopoeic expressions are effective enough to be terse, vigorous, and vivid to our ears as we have seen, and in some cases enough to make us feel restless or to heighten our tension. In this sense the following remark by Bloomfield is to the point: “Symbolic forms have a connotation of somewhat illustrating the meaning more immediately than do ordinary speech-forms",9 and so is Dr. Sakuma’s explanation: “Onomatopoeia portrays straight-forwardly in words what we cannot express happily by other conceptional or abstractive or descriptive words, and gets into harmony with other feelings, then appeals directly to our imagination."10 We might say, therefore, echo words are effectively symbolic of something sensitive, immediate and vivid rather than something rational, mediate and obscure. The English language is generally said to abound in monosyllabic onomatopoeias such as swish, crack, clank, etc. while Japanese does it by repetitive ones such as don-don [don doŋ], kachi-kachi [katSi katSi], etc. Keeping in mind this special feature of his native language, Wright avoids redundancy, then appeals immediately to the ears of readers by making the most use of echo words. In this story the sounds of the manhole cover, closely related to the main theme, are like rays being focused on clangs and clank, violently beating and deeply stirring the hearts of the readers.

* This is the English translation of my article in Studies in Linguistic Expression, No. 2 (1983), pp. 1-14. (An oral presentation of this paper was made in Japanese at the meeting held by Black Studies Association at Kobe City University of Foreign Studies on July 23, 1983.)

** Part-time lecturer in the Department of General Education at Osaka Institute of Technology

Notes

1 Cf. Inui Ryoichi, “Giseigo Zakki" (“Miscellaneous Notes on Onomatopoeia"), in Ichakawa Hakushi Kanreki Shukuga Ronbun Shu (A Collection of Papers in Celebration of the 60th Birthday of Dr. Sanki Ichikawa), 2nd ser. (Tokyo: Kenkyusha, 1947), p. 1.

2 Michel Fabre, The Unfinished Quest of Richard Wright, (New York: William Morrow, 1973), pp. 574-575.

3 Richard Wright, “The Man Who Lived Underground," in Cross-Section, ed. Edwin Seaver (New York: L. B. Fisher, 1944), p. 58; all subsequent page references to this work will appear in parentheses in this paper.

4 Cf. Otto Jespersen, “Sound Symbolism," in Language (1922, rpt. New York: Norton, 1964), pp. 399-400.

5 Cf. Inui, p. 4.

6 Cf. Inui, p. 3.

7 Richard Wright, Native Son (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1940), p. 3.

8 In the 1961 version (included in Eight Men) “asked" is changed into “ask."

9 Leonard Bloomfield, Language (1933; rpt. London: George Allen & Unwin, 1979), p. 156.

10 Cf. Sakuma Kanae, Nihongo no Riron teki Kenkyu (A Theoretical Study on Japanese) (Tokyo: Sanseido, 1943), pp. 18-19.

Cross-Section, 1944

執筆年

1984年 (Manuscript received May 31, 1984)

収録・公開

Memoirs of the Osaka Institute of Technology, Series B, Vol. 29, No. 1: 1-14.

ダウンロード

Some Onomatopoeic Expressions in ‘The Man Who Lived Underground’ by Richard Wright(115KB)