Human Sorrow – AIDS Stories Depict An African Crisis

概要

ムアンギの『最後の疫病』(The Last Plague, 2000)とゲテリアの『ナイスピープル』(Nice People, 1993)のケニアの小説が描き出したエイズの惨状を分析した作品論です。小説にしか描けない人の心理や性に対する考え方など、日本人に伝えると同時に、この500年のアングロサクソンを中心にした西洋諸国の侵略におかされて来たアフリカの将来への提言も分析しました。

本文

Human Sorrow:―AIDS Stories Depict An African Crisis―

TAMADA Yoshiyuki

The Faculty of Medicine, University of Miyazaki

<Summary>

This essay aims to show how AIDS stories in Kenya depict an African crisis that we have never seen in history. The AID situation in Africa is so devastating as is pointed out in a newspaper article containing the headlines; “Africa: the continent left to die – The Aids virus will kill 30 million Africans in the next 20 years. Are the drug companies making the situation worse?”1, but most of Japanese do not pay much attention to African issues including the emergent AIDS crisis, even though our country is closely related to some of the African countries through trades: The Japanese have prospered by making the best use of ODA (Official Development Assistance), an important instrument of neo-colonial strategies, in addition to investments and trade by having enhanced the alliances with the ‘nice people,’ a few chosen Africa elites. For example, Japan is one of the leading trading partners of Kenya as well as the most important ODA donor.2 Nevertheless, most of Japanese do not know even the existence of African literature.3 But they have high-standard literature in Africa. Nice People4 is a memoir which records the history of the outbreak of AIDS as early as 1984. The Last Plague5 is a novel which depicts everyday life of ordinary people suffering from HIV infection and AIDS.

I hope this essay will be some help to fill in the gap between the realities of Africa and the Japanese consciousness on Africa.

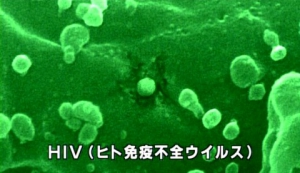

1.AIDS epidemic in the neo-colonial stage

It has been less than a quarter century since the word “AIDS" entered our vocabulary. It is in 1981 when the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) set up a special investigation team, which was the beginning of the first methodical study of the unknown disease. The team discovered that the symptoms were caused by a drop in T-lymphocyte cells, which play the key role in the cellular immune system that protects a human body from invasion of pathogenic organisms. It was then that the disease was given the name AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome). In the spring of 1983 the full proof of AIDS came and the virus is now generally called human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

CDC(米国疾病予防センター)

Since then, researchers have developed a number of drugs. In 1996 multi-drug therapy by a combination of reverse transcriptase (RT) inhibitors and protease inhibitors prolonged the lives of many AIDS patients. That year was heralded as the year AIDS treatment came of age, but none of the drugs shuts down the HIV life-cycle for long. Within a few weeks after it enters a body, HIV produces billions of genetically varied offspring. Drugs can shackle most of them, but a few survive and go on reproducing the offspring. Thousands of them look well but not everyone fares well with the drugs. Moreover, there have been some reports of problems with resistance and side effects.

抗HIV製剤

Effective multi-drug therapy can cost much. The price is tremendous, even in the industrialized countries. In the developing countries those drugs are financially completely out of reach as a report of the 1998 World AIDS Conference points out;

And even when the drugs offered hope, still other speakers said, it is hope beyond the reach of the vast majority of the 34 million people now infected the AIDS virus. Those patients cannot afford the treatment. It can cost about $15,000 to provide the drugs to one person a year, a sum greater than the entire budget of many a Third World village.6

It was in the early 80’s that the ADIS problem appeared in Africa. In such a short period the disease has spread much more rapidly than expected. An article in 1997 reports;

In the developing world, and especially in Africa, the virus continues to take an extraordinary, and often hidden, toll of suffering. It is estimated that 2,300,000 people will die of Aids-related diseases this year, a 50-percent increase on 1996.

The UN-Aids programme now admits that it has “grossly under-estimated” the number of people who have the HIV virus, and full-blown Aids, in Africa,…

The impact of HIV on this continent is so devastating that it has wiped out 30 years of gains from improved nutrition and medical treatment….7

Nice People and The Last Plague depict the devastating situation of AIDS in Kenya. The former story shows us the panic of the time when some doctors had to face this unknown sexually transmitted disease for the first time. The latter novel describes many suffering people in a withering village by the attack of the plague.

2.Nice People

The protagonist of Nice People is Joseph Munguti, a doctor in Kenya Central Hospital (KCH). In 1974, after graduating Ibadan University in Nigeria, he begins to work there.

At the university he was interested in STDs (Sexual Transmitted Diseases) and wrote the sub-thesis: “Kenyan morality and its effects on the epidemiology of Gonorrhoea and the Treponematoses." He insisted that “we would gain tremendous progress in the fight against venereal diseases were we to provide by extensive and intensive media communications acceptance of sexually transmitted diseases instead of moralising about and concealing them.”

He starts his internship under Waweru Gichinnga, his officer in-charge, who advises Munguti to work on night duty on a clinic in Nderu. Later Gicinga opens his own clinic, the River Road Clinic in Nairobi. The Nderu and River Road Clinics complement each other. As the law is vigilant in Nairobi, some operations can be illegally performed in Nderu. Most patients at Nderu contact venereal diseases (VDs). Ten years later Gicinga is arrested for his illegal treatments, so Munguti inherits the clinic as his own VDs’ clinic for the down-trodden in society.

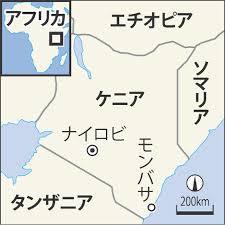

ケニア地図

In January, 1984, he reopens the clinic under a new name, believing he is the leading venereologist in the county and that there is no venereal disease he has not diagnosed and treated.

In December of 1984, however, a Chinese puzzle came to his clinic. At first he thinks it is a simple case of lymphogranuloma venereum, then, on a second visit, the sores that he thinks are simple genital herpes has spread all over the body. His patient named Kombo tells him that the patient tried all sorts of medicines without success. A friend referred him to Munguti and assured him that he would be cured.

Kombo says, “I am a rich man, young man. Here is twenty thousand shillings. Go and look for any medicine that will get rid of this."

Kombo and Munguti belong to the rich class. They are rich enough to use the Kenya Banker’s club “which was patronised by many members of the civil service, the big banks and government corporations. In this club most of the people in the who-is-who in Nairobi converged especially on Thursdays. It had five tennis courts, three squash courts, a sauna and a beautiful swimming pool which made it a particularly convenient rendezvous for Nairobi’s young bureaucrats.” (146)

ナイロビ市街

So, Munguti starts researching in the Kenya Medical Research Library and finds out the November issue of the “American Medical Journal":

A serious dermatological condition follows the genital herpes which resists all known antibiotic. Persistent diarrhoea, coughing and swelling of most lymph nodes accompanies the disease. Since the body is incapable of fighting many common diseases, the patient begins to wither away and eventually dies. It has been named the green monkey disease as the virus causing it is synonymous to the one similarly attacking the green monkeys of Central Africa! Several San Franciscan homosexuals are suffering from it."8

Munguti is certain that these symptoms were the same that he saw in Kombo. What he requires is a diagnosis with clinical tests and further research on causal factors, plus an understanding of Kombo’s background. He goes for a drink hoping to meet a medic with whom he can share his thoughts and comes across his old colleagues at the KCH. They confirm his fears that a new sexually transmitted disease has been diagnosed and is transmitted by a strange virus. It already killed five persons at the KCH, a Finish man, two Americans and two Zaireans. Three Kenyans were also admitted with the disease that week. The disease is highly contagious and is terminal. The men and women are therefore isolated in cages from other patients.

Munguti visits the KCH to look at the patients for comparative purposes. When he is taken by a nurse to a glass walled room where three men sleep, he feels such helplessness as he watches the helpless men anxiously looking at them. Then he recognizes his patient, Kombo. He froths at the mouth, archs his back and appears in great pain as he coughs repeatedly, a dry cough that is definitely puncturing his lungs;

“The one you were looking at is Major Kombo. Cleansing Superintendent of the Nairobi Garbage Handlers Company Ltd. They brought him yesterday and he is unlikely to survive another day," the nurse-in-charge advised and I started warming up in the heart. My guilt started waning as I recalled a battered Luo lady who years ago had come to the River Road Clinic complaining of a sodomist City garbage collection boss. I remembered thinking of going to the police station to report a felony, but declined because my medical profession barred me from doing so. Poor Major Kombo, I rationalised, his maker must have decided to avenge the women he had bestialized. (141)

Munguti asks the second opinion to his older colleague, Gichua Gikere. He already knew of the disease which was called “slim" and came from Uganda. Gikere talks about one witchdoctor. Although he does not believe in witch-doctors, he decides to go to the witch-doctor. But before going on the planned trip, Kombo passes away.

Munguti also has sexual realationships with three women: Mumbi, Mary Nduku, and Eunice Maimba, at the same time. They are all ‘nice people.’ He meets Mumbi, his colleague’s daughter at the clinic and is enchanted by her. They become intimate, finally promise to marry. But she has a white boy of Captain Blackman, whom she met in Mombasa as a prostitute, flees to to him in Helsinki just after childbirth. She dies of AIDS there.

モンバサ周辺地図

Mary Nduku, his friend from childhood, introduces Ian Brown at the Kenya Bankers’ Club to Munguti. She is a secretary and lover of Ian Brown, 34, an Englishman, who works for the Standard Bank and lives in Muthaiga, the Beverly Hills of Nairobi. His grandfather came to Kenya from South Africa. He drives a Jaguar and plays golf at the leading clubs. He dies of AIDS, too.

Eunice Maimba visits his clinic because of her husband domestic violence. At first she was only his patient but he finally found himself a “sugar boy” with a “sugar mummy”. Her husband passes away because of AIDS, too.

One morning he wakes up with swollen salivary glands and wonders:

I began wondering whether the dreaded disease that had been stalking me for the last ten years had finally caught up with me. Was it with Mary Nduku via Ian Brown? I asked myself, or was it Eunice Maimba through Godfrey Maimba? I sent a prayer to the heavens, then continued wondering if Mumbi, Dr. GG’s daughter, could also have been the cause of my problem. She had mothered a healthy child all right but this did not necessarily free her from seropositivity, or did it? I continued to ponder.

Captain Blackmann was a Finnish sailor who frequented Mombasa whore houses, so did Major Oluoch, Mumbi’s other associate. All this substraction and addition led to the fact that I was surrounded in the last ten years by likely pathways of the killer virus and there was to be no escape. I had coitus severally with the three women, who had done the same with three and more men who in turn had themselves been involved with others. I saw the picture similar to that of a spider-web that taps any flies that come into it and I knew we were all in the web. A sudden fear gripped me as I saw my mother listening to the news of her dear son’s final journey and its cause. (166-167)

Captain Blackmann was a Finnish sailor who frequented Mombasa whore houses, so did Major Oluoch, Mumbi’s other associate. All this substraction and addition led to the fact that I was surrounded in the last ten years by likely pathways of the killer virus and there was to be no escape. I had coitus severally with the three women, who had done the same with three and more men who in turn had themselves been involved with others. I saw the picture similar to that of a spider-web that taps any flies that come into it and I knew we were all in the web. A sudden fear gripped me as I saw my mother listening to the news of her dear son’s final journey and its cause. (166-167)

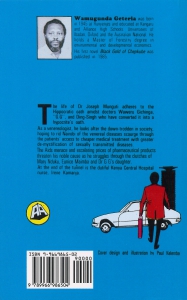

The author focuses on ‘nice people,’ for they are their ‘limited pool of professional and technical elite’ in the country who are to play the key role of treatment. The author’s note shows his concern;

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Among the things that made me embark on Nice people was this cutting from the Sidney Morning Herald sent to me in June, 1987. I reproduce it here 3 years after:

AIDS in Africa: the crisis that became a catastrophe by Blaine Harden

NAIROBI, Sunday: AIDS has infected up to a quarter of the population of some cities in central and eastern Africa, where it is now regarded as an unprecedented catastrophe.

The fatal disease is viewed as a particularly severe threat to Africa, the world’s poorest continent, because it appears to have spread among its limited pool of professional and technical elite.

Health authorities in Africa and observers elsewhere say the AIDS epidemic could, in a sense, decapitate some African countries.

The growing epidemic, these authorities agree, aggravates an already severe shortage of skilled people and raises the prospect of economic, political and social disorder. (VII)

著者解説付きの『ナイスピープル』裏表紙

3.The Last Plague

The Last Plague, on the contrary, focuses on many poor people, ordinary masses.

It is a novel of Janet, who tries to become independent through her job. When her husband, Broker left her family, Janet tried to kill herself, but didn’t. There were three children to raise and Grandmother. She was forced to become strong and conscious of herself in the society. She willingly took a job of the Government, which gave her condoms and pills to dish out, free of charge, in order to save the community from poverty and death. Her daily life is as follows:

She walked and pedaled her bicycle dozens of kilometers every day, from hill to hill and throughout Crossroads. She talked to numerous people every day; sang them the song of the condom and told them of the benefits of planning heir families and of protecting themselves from sexually transmitted diseases. Some listened to her, but most people did not want to hear her at all and she was unwelcome in many homesteads that she visited. Some ran to hide when they saw her coming, but she chased after them and did what she had to do and said what she had to say, no matter how hostile the reception, for it was her job, a vital and important job, and she did not have to convince herself of that any more.9

Crossroads, a small town in Kenya, is going to die. The text reads; “There were burial mounds everywhere one turned; large, brooding things, darkly vibrant with death, and there was hardly a single homestead in Crossroads that did not host one, or two or three or more, of these terrible reminders of the futility of man. And where thee was one today, tomorrow there would be two. Two became four and four became eight. Hey grew, they multiplied and they mutated. They turned into monsters: hungry beasts with insatiable carving for human life.” (22)

When her classmate Frank comes back home, he is much surprised to find the change of his native village. He left for education by villagers’ donation, he comes back, his education unfinished: “As he crossed the old highway into town, he realized that Crossroads had changed too. The joyous town of his youth had aged, and done so badly. The walls had caved in, the roofs had collapsed and the streets were lined with piles of rubble from countless dead buildings; mountains of crushed masonry and heaps upon heaps of decomposing dreams. Crossroads lay still and despondent, a disease-ravaged animal, hopeless and despairing, an affliction-ridden thing whose resistance to adversity had decisively collapsed, dying without whimper.” (24)

Broker comes back, too. He visits the house of Jemina, a woman with whom he left Crossroads for Mombasa, and found she is dead of Aids and her grandmother remains with many orphans. He is also surprised to find the devastation:

Broker left Jemina’s grave a thoroughly troubled man. The boy took his hands as they walked back to the huts and the other children. Two of the huts were now open. Broker pushed a door to look into a dark and dank room, smelling of urine and poverty. Rats scrambled from the floor and ran up the walls to their nests in the thatching. There was not a stick of furniture in the room. The entire floor was covered with sacks and sleeping mats. The second hut was in the same dismal condition; one vast sleeping place where rats ruled most of the day. A scrawny milk goat, with twisted horns, leaped out of the hut, startling Broker half to death, and bolted. (321)

Janet desperately tries to fight against Aids problems with the help of Frank and Broker, who thought themselves to be HIV-positive. Janet has to make a fierce battle with the villagers’ taboos and tradition:

Taboos and tradition had to go, they had to be eliminated, to make way for meaningful progress. Old believes and assumptions were the biggest handicaps in the battle of Aids, because they had many wives, and so-called safe partners, and did not manga-manga, or consort with prostitutes. But their safe partners too had their own safe partners, who also had safe partners; in an endless long chain of safe partners that was a recipe for a terrible catastrophe. (336)

At home Janet is assailed by a fixed idea of her Grandmother day after day:

“Talk about yourself,” Grandmother said. “You don’t even have a man of your own. What are you doing about it?”

Janet heard these words nearly every day of her life. The words hurt, and made her want to scream with fury, but she knew she would hear them till she married again or Grandmother died. (40)

“You must get married,” she said to Janet. “I worry about you and the children.”

“Marry again?” Janet asked her.

“Broker was a mistake,” she observed. “You have a right to marry again, another man. A proper man, someone who can look after you and your children. A real man.”

“A real man?” Jane scoffed at her. “In Crossroads?"

Janet saw where they were now headed with the conversation; down the old labyrinths and tedious dead ends that they had visited too many times already.

Janet laughed, wearily and without mirth, and reminded her there were not enough men in Crossroads who could take care of themselves, never mind their women and children. (42)

Janet visits schools to give sex education for children, a church to advise their congregation to use condoms, a witch-doctor to stop circumcise village boys, but meets a strong opposition. The witch-doctor, in revenge, smashes Frank’s animal clinic to pieces because he helped Janet.

The most difficult problem Janet has to face is the marriage of her sister’s husband, Kata, the witch-doctor. Following tradition, he will inherit the wife of his dead brother who has just died of Aids. Janet tries to persuade her to change Kata:

“You know I can’t stop Kata from doing anything,” Julia said to Janet. “You know how he is a traditional man.”

“Don’t you understand anything at all?” Janet was on the point of despair. “If Kata takes Solomon’s wife, he will die. Then Julia too will die.”

“Do you now know when people will die?” Grandmother was appalled.

“Do you think you know everything?” Julia said, defiantly. “I’m tired of your telling me what to do.”

“I worry for you,” Janet said to her.

“Don’t worry for me,” she rose in a huff. “You are no my mother.”

“I’m your sister,” Janet told her. “I must worry about you.”

“Monika is more of a sister to me,” Julia retorted. “We depend on our men. We are not prostitutes.” (57-58)

In spite of her efforts Kata marries his brother’s wife, but he reluctantly admits to use condoms with Janet’s sister influenced by the graphic book on Aids which Janet advised her sister to read. One day a team of inspectors from Oslo comes to see Janet. She shows them around to the schools, the church, the deserted houses with orphans, her house, and the condom shop Broker started.

It is an ironic ending the team decides to help Janet and the village, even though most of the villagers are still against the change of taboos and tradition.

The HIV test is given to all the villagers. Frank finds himself HIV-negative, and Broker makes sure of his infection. Soon after, Broker passes away.

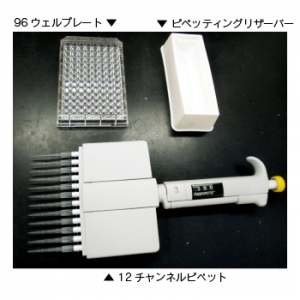

イライザ法検査器具

4.Human Sorrow

Now that the cause of the disease is clear, it seems possible to prevent the virus invasion. The two stories, however, show how difficult it is to control STDs and even more human desire. We feel even human sorrow.10

In Kenya, like in other African countries, the basis of the exploiting system is peasants and workers. When Europeans began to colonize African countries, they robbed Africans of their land and posed them various taxes, so Africans were forced to become landless peasants and workers. In Kenya some were forced to pick up tea as wage workers in white man’s farms and others to serve as domestic workers for white families.

ケニア地図

Under the colonial system companies and plantations needed foremen who served as mediators and could speak English, the language of the employers, which led to the development of a new type of administrative African middle class. They were given the privilege of going to school and learned much of European culture. They began to read criticism against colonialism. Some of them reacted against the cultural oppression in the colonies. Some of them were against social discrimination as a group, but they were tempted to imitate the Europeans’ privileged way of life. They led the fight toward independence.

Independence, however, gave nothing to peasants and workers, for the upper petty- bourgeoisie class and the petty-bourgeois tried to make an alliance with industrialized countries. We cannot deny that fact Japan is among them, the important trading partner. Some of our prosperities are based on the profits of investments and trades.

Now Aids has been added to the burden of ordinary African masses. The solution of the Aids problems is alternative: Africans like Janet will change the ‘taboos and tradition’ from inside or the side of the robber like Japan and the U.S.A. will concede even an inch in investments and trades.

Both are necessary.

HIV

Notes

1 Smith, Alex Duval. (September 12, 1999) Africa: the continent left to die. The Independent included in The Daily Yomiuri.

2 The Homepage of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan:

http://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/gaiko/oda99/ge/g5-12.htm

3 According to the questionnaires I made to the freshmen in April, 2004, just one student among 236 knew the existence of African literature. (The Faculty of Medicine -134, The Faculty of Engineering – 46, The Faculty of Agriculture – 56) In April, 2009. there are only 3 among 140 (1 nursing student and 3 medical students in the Faculty of Medicine.) Every year the situation is almost the same.

4 Geteria, Wamugunda. (1992) Nice People. Nairobi: African Artefacts. I happened borrow this book from my Kenyan friend. I was told he had got it in some overseas conference. I wrote to the publisher for some inquiries, but there was no reply. I’m afraid the publisher exists no longer. Now we can get a version by East African Educational Publishers and Michigan State University Press.

5 Mwangi, Major. (2000) The Last Plague. Nairobi: East African Educational Publishers.

6 Altman, Lawrenc A. (July 6, 1998) World AIDS Conference Ends Pessimistically, With No Cure in Sight. The International Herald Tribune included in The Japan Times.

7 Lichfield, John. (November 30, 1997) Lethal epidemic is much larger than feared. The Independent included in The Daily Yomiuri.

8 Nice People. 140. All subsequent page references to this work will appear in parentheses in this paper.

9 The Last Plague. 80. All subsequent page references to this work will appear in parentheses in this paper.

10 This work has been supported by JSPS. KAKENHI Grand-in-Aid-for Scientific Research (A) (15520230 – H.15~H.18) under the title: “Human Sorrow Seen between Medicine and Literature – AIDS Issues African Literature in English Depicts”

執筆年

2009年

収録・公開

Research and Practice in ESP (No. 10), pp. 12-20