概要

(写真と概要は作業中)

本文

Robert・Mangaliso・Sobukwe

ロバート・マンガリソ・ソブクウェというひと

(一) 南アフリカに生まれて

「ゴンドワナ」20号(1993)14~20ペイジ

ロバート・マンガリソ・ソブクウェ。一九二四年に南アフリカに生まれて、一九七八年に死んでいったソブクウェの名は、日本ではあまり知られてはいませんが、厳しい抑圧のなかでさえ、生涯渝(かわ)らぬ生き方をし続けたひとりのアフリカ人の生きざまに、私は強く心を惹かれます。

そして、三十年以上にもわたってソブクウェとその家族を支援し続けたベンジャミン・ポグルンドという人の存在にも、心を打たれます。

一九九◯年に出版されたポグルンドの伝記『ロバート・ソブクウェとアパルトヘイト これ以上美しく死ねるだろうか 』(ジョハネスバーグ、ジョナサン・ボール社)をもとに、ロバート・マンガリソ・ソブクウェというひとを紹介したいと思います。

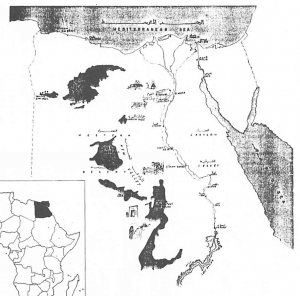

フラーフ・レィニェト

ロバート・マンガリソ・ソブクウェは、一九二四年十二月五日に、父ヒュバートと母アンジェリーナとの間の第七子として、ケープ州南東部のフラーフ・レイニェトに生まれました(六人の男の子のうち、三人は幼くして死にましたが、十歳違いの兄アーネスト、二歳上の兄チャールズと姉エレノアの三人は無事に成人しています)

ヒュバートの父親は、バソトランド(現在のレソト)の出身で、第二次アングロ・ボーア戦争(一八九九~一九◯二)前に家族とともにその地を離れ、戦争直後にフラーフ・レイニェトに移り住みました。ヒュバートは、そこでコサ系のポンド人アンジェリーナと知り合って結婚し、ソブクウェが生まれています。ほかの黒人と同じように、ソブクウェの出生が正式に登録されることはありませんでした。

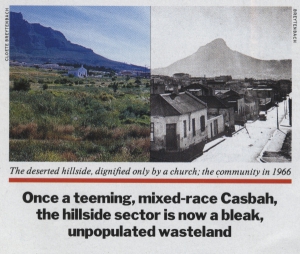

フラーフ・レイニェトは、ケープ州がオランダの統治下にあった一七八六年につくられた典型的な「白人」の町です。オランダ系の白人アフリカーナーが大勢を占め、町のはずれには、白人に安価な労働力を提供する黒人の居住区ロケーションがあります(一九二◯年の統計では、総人口一万七百十七人のうち、白人が五千百三十九人、カラードが三千六百七十七人、黒人が千八百八十三人、アジア人が十八人となっています)

カルーと呼ばれる赤土の乾燥性台地にあり、かつてはダチョウの羽毛の取り引きで栄え、今は羊や果物で潤おうフラーフ・レイニェトの町は、サンディズ川の恵みを受けて肥沃で、オランダ風の家並みも美しく、「カルーの宝石」と呼ばれています。

他の南アフリカの町と同じように、美しく整備された白人の町並みとは対照的に、ソブクウェの生まれたロケーションは、悪臭の漂う貧しい場所でした。もちろん、電気や水道の施設もありません。ソブクウェの育ったレンガづくりの家には、ほとんど家具らしい家具はなく、両親は古い鉄製のベッドで、子供たちは、土の地面の上にマット代わりに敷かれた麻袋の上で身を寄せ合って寝ていました。

父親は最初、町の役場に勤め、水路を維持する仕事をしていましたが、のちに羊毛の選り分けや、袋のラベル貼りをする店で働きました。かたわら、きこりのアルバイトもやり、町の市場で木を買っては家に持ち帰り、薪にしてロケーションで売りながら、家計を支えました。子供たちも交替で、朝早く起きて両親を助けました。母親は、何年もの間、町の病院の賄い婦や白人家庭のメイドとして働きました。

両親は、敬虔なメソジスト教会の会員で、住んでいる通りを「ソブクウェ通り」と名付けられるほど、ロケーションの人たちから尊敬されていました。自分たちは、貧しくて満足に学校に行けませんでしたが、子供たちには学校に行く機会を与えたいと願っていました。姉エレノアは、学校に八年間通ったのち、本人の希望ですぐに働き始めましたが、二人の兄は学校教育を終えて、教員の資格を取得しています。アーネストは、のちにイギリス聖公会の主教になりました。

ソブクウェは、ロケーション内のメソジスト教会の建てた小学校に六年間通いました。教会の長いすが机代わりの小学校の児童は黒人とカラードで、大半の子供たちは両親が貧しくて、途中から学校に来れなくなりました。小学校を卒業したのち、町にあるイギリス聖公会が経営する二年制の学校に四年間通いました。無償の初等教育とは違って、次の段階の中等教育を受けるための経済的な余裕が両親になかったからです。

高校から大学へ

一九四◯年、ソブクウェが十五歳の時に、兄チャールズと一緒に高等学校に行く機会が訪れました。学校は、フラーフ・レイニェトの町から二二五キロほど離れたヒールドタウンにあり、十九世紀にイギリスの宣教師達によってケープ州東部に創設された学校の一つでした。英文法と文学を基礎にしたキリスト教教育と教養教育が行なわれ、当時、黒人に教育の機会を与える中心的な学校でした。その年、高校に入学した黒人は五千八百八人で、全登録者数のわずか一・二五パーセントでしたから、ソブクウェも「選ばれた人」の一人であったことになります(黒人には義務教育の制度はありませんでしたから、「全登録者数」と言っても高校に入学する年齢層の一部にしかすぎませんでした。ちなみに、その年の白人の高校進学率は十六・四パーセントとなっています)

質素な寮生活でしたが、四十三年には、ケープ東部地域の黒人だけのテニスの試合で優勝するなど、スポーツに精をだしたり、学業に励んだりしながら、学校生活を楽しんでいます。際立った学業成績は白人教師の目をひき、三年間の小学校教員養成課程を終えたソブクウェは、その人たちに勧められ、学校の奨学金と校長のキャリー氏夫妻の援助を得て、二年制の大学進学課程に進みました。四十三年の八月から半年ほど、結核を患って入院していますが、復学してその課程を終え、四十六年末の大学入学許可試験では、優秀な成績を収めてフォート・ヘアの南アフリカ原住民大学(フォートヘア・カレッジ)に進学することになりました。

解放闘争への目覚め

フォートヘア・カレッジは、一九一六年に創設された黒人のための大学で、一時、白人が在籍していた時期もありますが、ソブクウェが入った年の入学者三百二十四人の内訳は、黒人二百六十人、カラード三十五人、アジア人二十九人でした。入学者のなかには、バソトランド出身者が十四人と他のアフリカ地域出身者が十八人含まれていました。女子学生はわずかに三十一人だけでした。

当時の黒人には、ケープタウンの大学とヴィットヴァータースランド大学のごく限られた枠以外に大学の門戸が開かれていませんでしたから、フォートヘア・カレッジには、優れた学生が集まりました。ボツワナの初代大統領セレツェ・カーマ、現ジンバブウェの首相ロバート・ムガベ、アフリカ民族会議(ANC)の元議長オリバー・タムボ、現議長のネルソン・マンデラなども、フォートヘアで学んでいます。

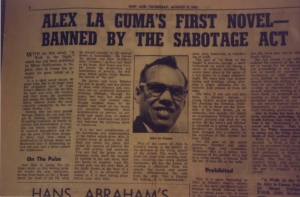

(本誌十号「セスゥル・エイブラハムズ アレックス・ラ・グーマの伝記家を訪ねて」のなかで、九十九パーセントが白人で、黒人には授業にでることと図書館を利用することしか許されなかったためにヴィットヴァータースランド大学を一年でやめたというエイブラハムズさんを紹介しています)

二つの奨学金と、両親と兄アーネストからの僅かな仕送り、それにキャリー夫妻の援助に支えられて大学生活を始めたとき、ソブクウェは二十三歳になっていましたが、スポーツや学科以外のことに、あまり関心を示しませんでした。すでに解放闘争に係わっていた友人デニス・シウィサが入学前にソブクウェを訪ねて、闘争の話を持ちかけましたが、ソブクウェのあまりの関心のなさに気分を悪くして帰ってきたというほどでした。

そんなソブクウェが、解放闘争への意識に目覚めて、やがては国を左右する指導者になってゆくのですが、フォートヘアでの三つの出会いや出来事がのちのソブクウェに大きな影響を与えています。

一つは、二年次に取った「原住民行政」学によって、見る目を開かされたことです。黒人を管理、統制する諸法律の研究としての「原住民行政」学を通して、それまで自分がミッション系の学校で如何に白人中心の歴史を教えこまれてきたか、また様々な手段によって黒人が如何に抑圧されているかを知り、愕然としました。自分も含め、白人でない人たちが、貧困が同居する人種隔離制度によって劣等の意識を植え付けられたうえ、惨状に黙従することに慣らされてしまっている現状を、強烈に意識し始めました。ソブクウェにとって、それまで考えもしなかった見方でした。

もうひとつは、セスゥル・ントゥロコとの出会いです。「原住民行政」学によって目を開かされたソブクウェは、「原住民行政」学を担当していたントゥロコに出会って、その見方を深めてゆきます。

ントゥロコは、ヒールドタウン、フォートヘア、ケープタウン大学を卒業し、南アフリカ大学の通信教育課程で「原住民行政」学を学んだあと、一九四七年から五十八年までの十二年間、フォートヘアで「原住民行政」学を担当しました。

二人が最初に出会ったのは、ソブクウェが代表挨拶をした新入生歓迎会の時でしたが、「原住民行政」学を取った二年次から、ソブクウェは親友のシウィサとガラザ・スタムパとの三人でントゥロコの研究室に入り浸るようになりました。話題の中心は主に政治で、「原住民行政」に関する本はもちろん、イーストロンドン発行の「デイリー・ディスパッチ」や、ナイジェリアやゴールド・コースト(現ガーナ)から送られてくる新聞なども読むようになりました。全アフリカ人会議(三十五年創設)を通じて、政治的にも強い関わりを持っていたントゥロコの感化を受けて、ソブクウェは、単に国内の問題だけでなく、独立への胎動を始めていたアフリカ諸国や広く世界の情勢についても考えるようになっていきました。

最後のひとつは、ソブクウェが政治的に目覚め始めたのと、アパルトヘイト政権の誕生とが重なったという時のタイミングです。

三十年代前半に国民党と南アフリカ党の連合によって与党となり、三分の二以上の議席を獲得した統一党は、数の力にまかせて、三十六年には「原住民代表法」と「原住民信託土地法」を制定し、それまでケープ州一部の黒人に与えられていた投票権や土地の所有権を奪って、人種による隔離政策の礎を築き始めました。そして、一九四八年、時の事態をさばき切れなくなった統一党に変わって、国民党マラン政権が誕生し、オランダ系白人アフリカーナー、特に低所得者層のアフリカーナーの熱烈な支持を受けて、アパルトヘイト政策を強力に推し進めました。ソブクウェが二年生、「原住民行政」学に目を開かされ、解放闘争に関心を持ち始めたころのことです。

だんだんと厳しくなる抑圧に対抗して、黒人側もANCを中心に運動の新たな局面をむかえていました。四十三年には、それまでの消極的な闘い方に不満を抱くマンデラやタムボなどの二十代の青年たちが、ANCに承認されてユース・リーグを結成し、国内のヨーロッパ人と同等の諸権利の即時獲得を求めて激しい闘いを展開し始めました。やがて、フォートヘアにもユース・リーグの支部ができ、ソブクウェは友人とともに、中心的な役割を果たすようになります。

四十九年には、ヴィクトリア病院の看護婦のストライキの支援活動を通して、生涯の伴侶となるヴェロニカ・ゾドゥワ・マテと出会っています。卒業年次の五十年には、母校ヒールドタウンから教職の誘いがありましたが、断っています。説得に駆けつけた支援者のキャリー氏に、自分が立ち向かうのは白人ではなく、白人至上主義だとソブクウェは説明しますが、理解されず、それ以降の援助金も打ち切られました。白人の目に適った「原住民」の優等生だったソブクウェは、フォートヘアで、体制に立ち向かうアフリカ人に生まれ変わっていたのです。

五十年にフォートヘアを卒業したソブクウェは、トランスバール州スタンダートンのジャンドレル高校に赴任することになりました。

ヴェロニカとポグルンド

ジョハネスバーグから百六十キロ東にあるスタンダートンも、ロケーションをもつ典型的な白人の町でした。電気も水道もないロケーションは貧しく、学校には図書館もホールもありませんでした。週に五日、毎日八時から二時まで、歴史と英語と聖書の科目を担当し、聖歌隊の指導などもやりながら、教員でクラブチームを作ってテニスやサッカーに興じたりもしています。生徒や教師の間での信頼は篤く、一九五二年にANCが展開した不服従闘争の際にスタンダートンで集会を持った責任を問われて職を失ないかけましたが、学校の後押しもあって、以後政治を学校に持ち込まないという誓約書を書かされるだけで済んでいます。その年の暮れに、父親が亡くなっていますが、しばらくは教員としての穏やかな日々が続きました。

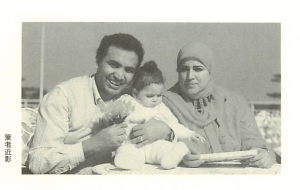

一九五四年の六月に、ソブクウェはその後も交際を続けていたヴェロニカと結婚し、すでに採用が決まっていたヴィットヴァータースランド大学バンツー語学科語学助手として、ジョハネスバーグのソウェトに移り住みました。講師よりも待遇は悪かったものの、ほとんどが白人で占められていた教職員のなかにあって、語学助手は黒人に許された唯一の常勤職でした。ソブクウェ自身はコサ語を話しますが、初心者のための実用ズールー語を担当することになりました。結婚当初、二人はヴェロニカの母親の家に同居しましたが、九ヵ月のちには、市営の住宅に移りました。白人のための労働力としてタウンシップに住む黒人には、家を買う権利は認められないうえ、入居する家は内装もされておらず、内装の工事に二百ポンドもかかっています。二百ポンドは、結婚の際にソブクウェがヴェロニカの母親に贈ったお金の二倍、大学での年収の半分近い金額でした。

寝室と居間、それに食堂と台所だけの小さな家で、電気もなく、ロウソクの火と灯油ランプの生活が続きました。母親の家で女の子が、新居に移ってから三人の男の子が生まれて家が手狭になりましたが、「夫は子供たちが大好きで、子供たちと一緒に過ごす時間も多く、よくお話を、特にコサのお話を語って聞かせていました」とヴェロニカが述懐するように、子供をまじえた楽しい家庭でした。朝七時に家を出て、五時半頃には家に帰る毎日で、家についている小さな畑で花や野菜を作ったりもしています。

五十五年にヴィットヴァータースランド大学の名誉学士課程への登録を認められ、二年間、音声学や社会人類学などを学んだのち、五十八年に名誉学士号を得ています。翌年から、政府は「白人」大学への黒人の入学を禁止し始めましたから、ソブクウェはバンツー語学科の名誉学士課程への登録を許可された最後の「黒人学生」となりました。

五十九年には、アフリカ人作家に関する諸宗派会議の顧問に指名されて、強化される検閲制度に反対する意見を述べたり、オクスフォード大学出版局のアフリカ言語の出版顧問をしたりするなど、語学の分野での地位を固めていきました。

しかし、楽しい家庭生活や守られた大学での教員生活に、ひとり満足しているわけにはいかなくなりました。まわりのソウェトの現実と時の情勢があまりにも厳しすぎたからです。フォートヘアで育んだ「新しいアフリカ」への思いを温めながら、ソウェト内のANCモフォロ支部に所属したソブクウェは再び解放運動に身を投じることになりました。定期的に自宅で会合がもたれ、ソブクウェのもとに、次第に人が集まるようになりました。 一九五七年、ポグルンドが最初にソブクウェと出会ったのは、そのような時期でした。当時、ポグルンドはある工業系の会社に勤めながら、自由党のトランスバール州委員会のメンバーとして、ソフィアタウン地区の黒人の支援活動をしたり、不服従運動にも加わったパトリック・ダンカンの主宰するリベラル派の雑誌「コンタクト」に寄稿したりするなど、反アパルトヘイトの運動に積極的にかかわっていました。ANCの会員を通してアフリカニストとしてのソブクウェの名前は既に知っていましたが、二人が会ったのはポグルンドが婚約者をヴィットヴァータースランド大学の教室に迎えにいった時のことです。ズールー語を受講していた婚約者が、たまたま講義室に居合わせたソブクウェを紹介してくれたのですが、第一印象はいかにも学者ふうで、気の弱そうなという感じだった、とポグルンドは述懐しています。当時、親しい人の間ではロバートとかマンギーとかロビーとか、支援者の間では「教授」とかと呼ばれていたソブクウェを、ポグルンドはボブと呼び、ソブクウェはポグルンドをベンジーと呼び合うようになりました。四月の終わりにはポグルンドが、ソブクウェに「コンタクト」への寄稿を依頼しています。ソブクウェは快く応じましたが、共産党員の妨害や白人受講生の懸念を恐れて、ペンネームで原稿を書いています。ポグルンドは、原稿を見て、アプローチの仕方が幼稚で、はっきりとした政治的な考察に欠けているという印象を持ちました。

しかし、五十八年の半ばにポグルンドがジョハネスバーグの英語朝刊紙「ランド・デイリー・メイル」の記者になった頃には、ソブクウェに対する印象ははっきりと形を変えていました。最初にソブクウェから感じた気弱なイメージが、実はソブクウェ流のためらいで、楽しい家庭生活や守られた大学の生活と黒人の自由を獲得するための闘いとの狭間で、自分が何をすべきかを決めかねている正直な人間の苦悩であったと理解したのです。六月半ばには、ある友人にあてた手紙のなかで、ポグルンドは次のように書いています。「ソブクウェは気高く、明晰で、思慮深く、極めてすぐれた感性の持ち主でした。接すれば接するほど、私は好きになって、感化を受けています……何とも偉大な男です」

五十八年初めに、ローレンス・ガンダが編集長になってから「ランド・デイリー・メイル」は、黒人地区での取材をもとに、黒人の活動や居住区の生活などをより多く報じるようになり、体制批判の色合いを強めました。したがって、ポグルンドも記者として黒人居住区や集会に頻繁に出入りすることになり、公私にわたるソブクウェとの親交もますます深まっていきました。

パン・アフリカニスト会議

四十八年からの十年間で、国民党政権は体制を固め、五十八年四月の第二回の白人だけの選挙では三分の二の議席を確保して、更に徹底した体制づくりを開始しました。

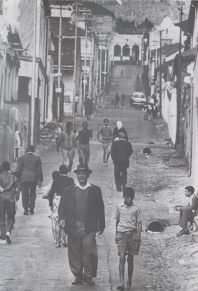

集団地域法によって、居住区だけでなく、商業区域も人種による分離が明確にされただけでなく、白人に都合のいい居住区が強制的に白人地区に塗り替えられていきました。その結果、追い出されたり、色々な都市から流れてきた黒人が、ジョハネスバーグ南西部の広大な農地に移り住んで、ソウェトが生まれたりもしています。

ロケーションの再編成に向けて、農村部での強制立ち退きも行なわれ、政府主導型の「原住民政策」が強力に推し進められました。

ストライキも組合活動も法律で禁じられた黒人労働者は、白人雇用者の思いのままで、労働局の設定する最低賃金さえも保障されずに、大多数が生活最低基準以下の生活を強いられました。

黒人・白人間の教育費や教員の賃金の格差は広がり、白人大学への入学制限や政府の夜間学校への妨害などで、黒人の教育への門戸はますます狭められていきます。

背徳法やパス法での締め付けも厳しくなり、列車だけでなくすべてのバスにもアパルトヘイトが適用されるようになりました。

五十八年に首相になったヘンドリック・ファブールトは、政府のブレーン南アフリカ原住民問題局(SABRA)に「分離発展」の政策を研究させ、ミニ独立国家を作って黒人を外国人に仕立てるという、のちのバンツースタン政策の基礎がためを始めました。

こうした厳しい状況のなかで、ANCは大きな転機をむかえていました。政府の圧政に対抗するという問題のほかに、もう一つ大きな内部事情を抱えていたからです。指導部の指導力不足や財政難による軋轢(あつれき)もありましたが、何よりの問題は、アフリカ人による、アフリカ人の闘いを主張するアフリカニストを中心にする闘い方の路線をめぐっての紛糾でした。反逆裁判や活動禁止処分などによる政府の激しい締めつけに対抗して指導部を支持するようにという要請にもかかわらず、ケープ地区では既に二派に分裂、五十七年の半ばには、トランスバール地区で二派の対立が公の場に持ち出されるほどの事態に陥りました。闘い方の路線をめぐる対立は、もはや単なる各地区だけの問題ではなく、ANC全体の今後を左右する大きな課題となりました。

そうした緊迫した状況のなか、五十八年十一月はじめに、年次総会と特別会議を兼ねたトランスバール会議が開かれました。富の平等な分配をめざして、肌の色や人種の区別なく共闘するのがANCの基本方針だとする指導部と、闘い方が四十九年に採択された行動計画に沿っておらず、階級闘争を掲げるコミュニストや他の人種との協調の度合いに比べて、アフリカ人同士の団結の問題が軽視され過ぎていると主張するアフリカニストが真っ向から対立しました。実行されませんでしたが、会議の主導権を握るために、アルバート・ルツーリ、タムボ、マンデラなどの指導層を会議の前夜に誘拐するという計画もありました。それだけ、白人やコミュニストと協調しながら闘ってきたANCの柔軟路線に対するアフリカニストの積年の不満が大きかったということでしょう。一方では、アフリカニスト三人を狙撃するために三人の殺し屋が雇われていたという話もあります。ソウェト十人委員会で知られる医師タト・モトラナのように、アフリカニストに協力的で、コミュニストに感化され過ぎる指導部に批判的であることは認めながらも、隣国ジンバブウェなどの例をあげて、それでも分裂だけは回避すべきだと主張した人もいましたが、だれも時の流れを食い止めることは出来ませんでした。

この段階でソブクウェが一番恐れたのは、アフリカ人同士による流血の惨事でした。出席者六百人のうちの百人を占めるアフリカニストの多くは長い棒切れをもって、後部席に陣取っていました。夜になって、公式代表の審査をする資格委員会の選挙の開票の際には、会場内は緊迫し、一触即発の状態となったため、ソブクウェたちは、会場の外に出たほどでした。ただ一人の白人出席者ポグルンドも、危害が及ぶかも知れないと両陣営から忠告を受けて、会場をあとにしています。翌朝、タムボはこん棒などをもった百三十人の護衛隊を引きつれて会場に臨み、入場を厳しく制限してアフリカニストを締め出したため、ANCの分裂が決定的となりました。午後五時に、ソブクウェの起草した手紙がタムボに手渡されました。

この時期のソブクウェは、解放闘争と大学の教職との狭間で、個人的に非常に苦しい立場に立たされ、厳しい選択を迫られていました。積極的に闘争に係わっている以上、もはやヴィットヴァータースランド大学にはいられないと思い始めた頃、ケープ州東部グラハムズタウンのローヅ大学バンツー研究科から、常任講師としての誘いがあったからです。これ以上は政治に係わらないという誓約書を、との条件が付いていましたが、待遇や社会的な地位、あるいは将来性などから考えても、通常なら、願ってもないチャンスでした。迷いながら、とりあえず誓約書の件だけは断ったものの、最終的な判断を下せないまま、時が過ぎていきました。

ANCと決裂した五ヵ月後の五十九年四月、アフリカニストたちは、同じ会場で新しい組織の結成式を行ないました。会議は、予定より三分早く始められました。二時間や三時間、遅れることが当たり前になっていたANCの旧弊から、先ずは改めようというソブクウェの意気込みでもありました。会議では、パン・アフリカニズムを唱えるガーナの首相エンクルマやギニアのセコゥ・トゥレ大統領からのメッセージが読み上げられたあと、パン・アフリカニスト会議の名称と緑・黒・金の三色のシンボルカラーが採用され、議論の末、次の五つの目標が決められました。

(一) アフリカ・ナショナリズムに基づいた国民戦線に、アフリカ人を統合、集結させること。

(二) 白人支配を打倒するため、また、アフリカ人のための自己決断の権利を履行、 保持するために闘うこと。

(三) 各人の物質的、精神的な利益を優先するアフリカ社会民主主義を打ちたて、維持するために働き、尽力すること。

(四) アフリカ人の教育的、文化的、かつ経済的発展を促進すること。

(五) アフリカ人同士の連帯を強めることによって、南アフリカ同盟とパン・アフリカニズムの概念を伝え、広めること。

そして、満場一致の推薦をうけて、ソブクウェが議長に選ばれました。(続)

一九九二年春 宮崎にて

*二十一号の続編には、ソブクウェの年譜と南アフリカ小史を添えています。

* *

[参考]

南アフリカ観光局(東京都港区赤坂)発行の「南アフリカ全国主要観光地ガイド」には、ソブクウェの生まれたフラーフ・レイニェトが次のように紹介されています。

Graaff-Reinet/グラーフ・レイネ■1786年以来の由緒ある町。中でも1812年に建った 古い牧師館レイネ・ハウスはケープ・オランダ風住宅の粋といえる優雅な佇まいをみせている。後年の修復も原型を損なわぬ見事なもので、内部は18~19世紀の家具で飾られている。裏庭の葡萄の木は1870年に植えたとか、幹の太さは世界一と評されている。開館:月~金09:00~12:00・15:00~17:00、土09:00~12:00、日祝10:00~12:00。十字架と切妻屋根が美しいオールド・ミッション・チャーチは修復されて南アフリカの代表的な芸術家たちの作品を集めた“ヘスター・ロバート・アートコレクション”を展示している。開館:平日10:00~12:00・15:00~17:00、土・日・祝10:00~12:00。レイネ・ハウスの向かい側にあるレシデンシー館や、ドロスティホフ通りに並ぶ19世紀の木造建築も美しく、見逃せない観光スポット。

執筆年

1993年

収録・公開

「ゴンドワナ」20号14-20ペイジ