概要

アフリカのエイズの深刻な状況を、ジンバブエの例を軸に、分析したものです。

ヨーロッパ人はアフリカ人から土地を奪って課税することによって大量の低賃金労働者を作りましたが、売春婦が通う労働者の住まいがエイズ感染の温床になっています。売春婦を介して感染した男性が、村に帰って配偶者に感染させて事態を深刻化しています。最新のエイズ治療薬も大半のアフリカ人には無縁です。そういった負債とエイズに苦しめられているアフリカの危機的な状況を分析しました。アフリカと医学をつなぐテーマとして医学生の英語の授業で取り上げる中から生まれました。

本文

アフリカとエイズ

深刻な状況

アフリカのエイズ事情は深刻である。

その深刻さを伝える二つの記事は、私には衝撃的だった。

一つは、英日刊紙「インディペンダント」(1995年7月)のジンバブエについての報告記事で、「たいていの女性にとって、HIV感染の主な危険要因は、結婚していることである」という一節である。(註1)

もう一つは、英科学誌『ネイチャー』(1999年7月)の記事で、アメリカの製薬会社の突き上げを喰って、大統領選出馬の野心を抱く副大統領ゴアが、南アフリカに対して頻りに、コンパルソリー・ライセンス法撤廃への圧力をかけているという内容だった。(註2)

画像『ネイチャー』(1999年7月)

アフリカで実際にエイズ治療に当たった医師は、その深刻さを肌で感じ取っている。

英国人医師リグビィ氏は「アフリカで働こうと心に決めたとき、アフリカのエイズ問題の深刻さを私は充分承知している、と信じていました。しかし、(アフリカでの医療活動を経験した)今、本当に事態の深刻さが分かっている人がいるとは、私には信じられません。」と『イギリス医学誌』(1995年6月)のなかで告白している。(註3)

1998年8月のケニア米大使館爆破事件で、血塗れの犠牲者の救急治療に当たる医療関係者のニュース映像を見ながら、米国人医師スティーム氏は、背筋の凍る思いをしたと誌している。(註4)

スティーム氏はケニアでの医療活動経験者で、爆破事件の時も、エイズ事業の視察を終えたところだった。ナイロビでの若者成人人口のHIV(ヒト免疫不全ウィルス)感染率は約25パーセントで、手術を伴なう救急治療室でのHIV感染の危険度は極めて高いと言われている。今回の視察で出会った若い米国人外科医は、ボランティアとして田舎の病院で複雑な手術を行なう予定だったが、感染に備えて、二重の手袋をはじめ、ケニアでは入手出来ない緊急時用の抗HIV剤などと、輸血の必要性が出た場合にヨーロッパの病院に空輸してもらえる保険の準備をしていたという。それだけに、手袋もつけずに血塗れの患者の治療に当たるケニア人医師や看護婦たちの映像を見た時の衝撃は大きく、現状では「悲しいことだが、エイズ流行病で爆破以上の死者が出て、その死者の中にはこの事件で危険に晒された医療関係者が間違いなく含まれるだろう」と予測せざるを得なかった。アフリカの厳しい現状を垣間見た者の偽らざる実感だろう。

HIV

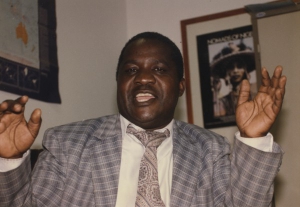

私もジンバブエに滞在したあと、よく似た思いに捉われたことがある。

1992年に、私は首都ハラレで、家族と過ごす機会を得た。住宅事情が悪いらしく、ホテル住まいも覚悟していたが、運よく一軒の家を借りることが出来た。家賃は月約十万円で閑静な白人住宅街にあり、約五百坪ほどの広さだった。

ハラレ借家

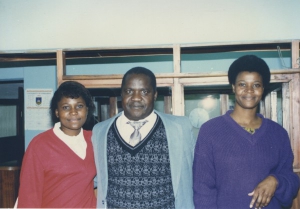

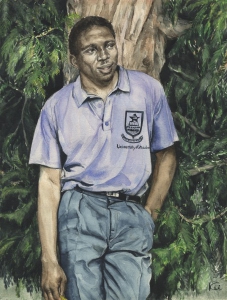

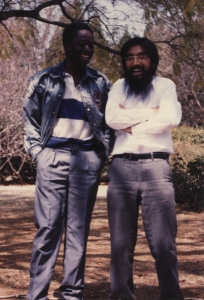

ゲイリーというアフリカ人青年と大きな番犬が私たち四人を出迎えてくれた。ゲイリーは「ガーデン・ボーイ」(庭番)として家主のスイス人老女に雇われており、庭の片隅の小さな部屋に独りで住んでいた。

ゲイリーとデイン

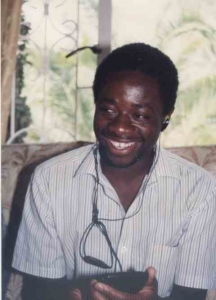

アフリカで家族と暮らすのが滞在の主な目的だったので、ゲイリーとはすぐに仲良くなった。長い休みに入るころ、家族を呼び寄せて、狭い部屋に五人で暮らし始めた。ゲイリーの子供と私の子供も、奥さん同士もすぐ仲良しになった。同じ敷地内で、二ヵ月半の大半をゲイリーの家族といっしょに過ごすこととなった。

庭で遊ぶ庭で子供たち

ゲイリーの月給は四千円ほどだった。経済格差があるので単純には比較できないが、子供たちに買ったバスケットボール一個が五千円ほどで、ゲイリーの給料よりも高かった。女性の給料は更に低く、一日二百円ほどで「メイド」が雇え、普通は朝八時から夕方の四時までが勤務時間のようだった。日本にいる時に、南アフリカでは洗濯機を買う人がいないと聞いたことがあったが、「メイド」がはるかに経済的な「洗濯機」の機能を果たしていたわけである。

ある日、運転手付きの車を借りて、ハラレから少し離れたゲイリーの田舎の家を訪ねた。何家族かの親戚が集まって暮らしていたが、むこうの丘の麓辺りまでが家の土地だとゲイリーが教えてくれた。ずいぶん広い土地がありながら、かつてはゲイリーの父親が、そして今はゲイリーが、家族と離れて一年の大半を街で過ごす生活を余儀なくされていた。

ゲイリーの家

1505年のヴァスコ・ダ・ガマらによるタンザニア沖合の島キルワでの虐殺を皮切りに、西洋人はアフリカ大陸の侵略を開始した。西アフリカでは奴隷を売買して富を築き、蓄えた資本によって産業革命を起こす。人類は生産手段を手動から機械に変えて、大量の製品を作りだすようになる。製品を売り捌く世界市場が必要となり、市場の争奪戦が繰り広げられた。植民地時代の幕開けである。アフリカはその餌食となった。

侵略の要は、効率よく人のものを掠めとる点にある。まずアフリカ人から土地を奪い、課税をする。貨幣経済に巻き込まれたアフリカ人は僅かな現金を求めて村を離れ、都会に出て行くしかない。あり余る低賃金労働者の出来上がりである。季節労働者と呼ばれる人たちで、通常は14ヵ月くらいの短期契約である。パートタイム契約は馘切りも簡単で、賃上げの心配も少なく、経営者側には効率のいい雇用形態である。鉱山や農場脇のコンパウンドと呼ばれるたこ部屋で、一年の大半を家族と離れて過ごす。あるいは、白人家庭で「ボーイ」や「メイド」と呼ばれながら、家内労働者として扱き使われる。

ゲイリーもその一人だった。庭木の水遣り、番犬の世話、老女のための買物や使い走りがゲイリーの仕事の内容だった。一月四千円余りの賃金で大の男が一日の大半を拘束されて過ごす。名こそ奴隷ではなかったが、扱き使われている事実に変わりはなかった。帰国当日の朝にスイスから戻った老婆の電話を受けたゲイリーの狼狽振りは、見ていても気の毒なくらいだった。家に入る時は靴を脱ぐように命じられていた「ボーイ」が、私たちの友人として、こともあろうに「靴を履いたまま」居間で寛いでいたからである。(註5)

庭でゲイリーと

アフリカに行く前、私はアフリカの状況を一応は知っているつもりでいたが、アフリカの現実は圧倒的すぎた。帰国して目にする「日本」との格差がありすぎて、しばらくは心の整理がつかなかった。

それだけに、アフリカのエイズ事情の深刻さが、身に沁みる。

歴史の皮肉

『HIV感染症』の著者秋山武久氏は、梅毒とエイズの二大性病をハイチ人が媒介したという説を支持している。(註6)

コロンブスがハイチ島から持ち帰った風土病がのちに梅毒として世界に広がった、ザイールに滞在していたハイチ人が持ち帰ったHIVがハイチ島内での流行を経てアメリカへ伝播されたという説である。いずれの場合も、それほど激しくなかった風土病が、感染経験のない地域に伝播して、突如猛威をふるいだしたというものである。

かつて「奴隷調教」の場に利用された(註7)カリブの島「ハイチ」から運ばれた風土病にヨーロッパ人侵略者たちは苦しめられた。今また、アフリカからカリブの島を経て侵入した病原体に侵略者の子孫たちは悩まされている。歴史の皮肉である。

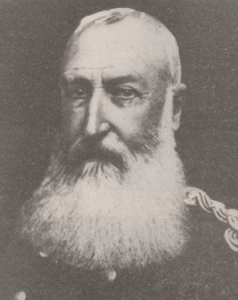

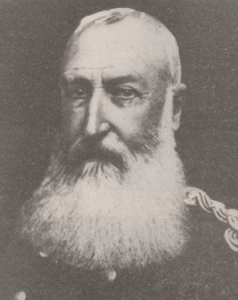

今回の場合、アフリカ内陸部に住む人たちの間で蔓延していた風土病が、売春婦を介して都市部へ伝播してHIV感染症に変貌し、その病気が圧政を逃れて帰国したハイチ人によってハイチ島に運ばれ、島内流行の後、アメリカに渡ったと考えられている。風土病の山村から都市部への伝播とハイチ人の移動は、レオポルド二世→ベルギー→モブツと続く容赦のない圧政によってもたらされた人々の貧困と深く係わっている。ことに、モブツ独裁政権を長年に渡って公然と支援し続けたのがアメリカであってみれば、エイズは侵略者への見事なしっぺ返しである。

レオポルド二世

しかし、最大の犠牲者はアフリカ人である。奴隷貿易、植民地支配を経て、今も続く新植民地支配に喘ぎながら、HIV感染症の追い打ちを受け、今やまさに大陸存亡の危機に瀕しているのだから。

HIVの特徴、アフリカの特異性

HIVの特徴は、病原ウィルスが主に、免疫を司るリンパ球ヘルパーT細胞を標的にして増殖し、感染者の免疫力を低下させることである。しかも、現在のところ、一度感染すると、ほぼ全員が感染死する不治の病である。

1981年に最初のエイズ患者が発見されてから数年後には、ウィルスの構造や伝播形式も明らかにされている。したがって、感染の予防方法も確立されているわけだが、感染者は増加し続けている。この流行病が、主に異性間性交によって伝播される性感染症であるためである。

数年前に人々を震撼させたザイールのエボラ出血熱やインドの肺ペストなどの感染症は、致死率は高いが潜伏期間も短かく、そのうえ地域封鎖などの厳戒体制が敷かれるため、患者が回復するか、死亡するかすれば一応の終息をみる。

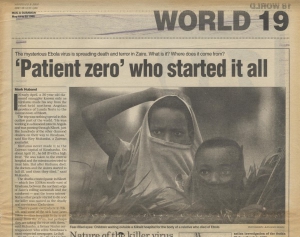

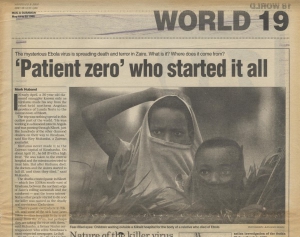

南アフリカの週間紙のエボラ出血熱の特集記事

それに比べて、このHIV感染症は、極めて質(たち)が悪い。感染しても無症状の期間が長く、その間、無意識に、ある場合は意識的に、二次感染が起こるからである。ウィルスの恐ろしさを知らなければ、当事者に意識されることもなく、性交渉を通じて病気は蔓延していく。

アフリカ大陸、特に南部はHIVの温床である。ヨーロッパ人が大量の低賃金労働者を作り出して、鉱山や農場近くのコンパウンドに住まわせていると書いたが、実は、そのコンパウンドに売春婦が通う。鉱山労働者が汗水流して稼いだ僅かな賃金のおこぼれにあずかるためである。「(ジンバブエの)ムランビンダ村の四千人強の人口の約10パーセントが売春婦で、鉱山労働者とほぼ同数である。その約半数の売春婦がHIVに感染していると警察は信じている」と報告記事が伝えている。(註8)

ムレワのゲイリー家族

売春婦を介して感染したアフリカ人男性は、契約が切れて村に帰り、その配偶者に感染させる。多重婚のところも多く、男性は通常、複数の性交渉の相手を持つ。しかも、統計によれば、男性から女性に感染させる率の方がはるかに高い。

そういった様々な事情が折り重なって、冒頭に引用した「たいていの女性にとって、HIV感染の主な危険要因は、結婚していることである」という悲劇が起こる。そして、男性の働き手を都会に吸い上げられている農村部では、不可欠な労働力として、あるいは残された子供や老人の世話をする担い手として農村経済を支えている女性たちが、次々とエイズにやられ、たくさんの子供たちを残して死んで行く。経済面でもその基盤そのものが、まさに崩壊しようとしているのである。

どの民族であれ、結婚していることが不治の病に感染する危険要素ならば、どうやって子孫を増やしていけばよいのか。娘たちに死なれ、残された年寄りたちはただただ途方に暮れる。

どうして子供らはみんな、死んでゆくんだろう?どうして若い者たちは、わたしら年寄りに孤児(みなしご)を残して、逝ってしまうんだろう?

そんな老婆の哀しみを伝える冒頭の記事(註9)は、1995年7月のものである。もう四年以上が経過した。

エイズ会議

1994年8月に横浜で開かれた第10回国際エイズ会議は、記憶に新しい。日本での開催とあって、アジア諸国のエイズ事情が詳しく紹介されたり、母子感染の際の逆転写酵素阻害剤AZTの効果や感染者の長期生存の症例報告があったりなど、会議の成果が日本でも連日報道された。(註10)

1996年のヴァンクーバー会議では、従来の逆転写酵素阻害剤と、新たに開発された蛋白分解酵素阻害剤を併用する多剤療法の効果が報告されて、エイズが、ウィルスとの共生も可能な病気になるかもしれないと、誰もが希望をもった。その年をエイズ治療元年と呼ぶ記事も少なからずあった。(註11)そして、ワクチン開発への希望も膨らんだ。

しかし、1998年のウィーン会議は「視界に治療法も見えぬまま、悲観的に閉幕」した。(註12)多剤療法で副作用が出たという症例報告や、ワクチンの開発がむしろ後退している現状報告に、会場は重い空気に包まれた。そして、病気への最大の戦略は、やはり予防しかない、と再確認せざるを得なかった。

次回2000年のエイズ国際会議開催国南アフリカ、ダーバンの医師は「ダーバンの大きな黒人用の病院で治療にあたる子供たちの40パーセントがエイズ患者です」と言う。国際会議で議長を努める予定のその医師は「私は今まで抗エイズ治療薬を使ったことはありません。病院には治療薬を使う経済的な余裕はありませんから」と付け加えた。参加者はアフリカの厳しい現状を突き付けられて、ますます気を重くした。

しかし、そんな深刻な状況を、アフリカ諸国も、自称「先進国」も、深刻に受け止めているとは思えない。

本年9月のザンビアでのエイズ会議にアフリカの首脳は参加しなかった。世界で最も事態が深刻だとされる南部アフリカ六ヶ国は、大統領はおろか、一線級の官吏さえも送らなかった。主催国ザンビアの大統領も、会議に出なかった。エイズ患者、医療関係者、研究者など数千人が集まって、何とか対抗策を見いだせないものかと真剣に討議をしたにもかかわらずである。(註13)

「死にゆく大陸」

今のアフリカに、エイズよりも緊急の課題があるはずがない。

今夏、「エイズが問う『政治の良心』 南ア特許法に米が反発」という記事が出た。アメリカのゴア副大統領と通商代表部が、南アフリカ政府が1997年に成立させた「コンパルソリー・ライセンス」法を改正するか破棄するように求めているが、その圧力が不当な干渉であるという主張である。(註14)

感染者がエイズ治療薬の恩恵を受けやすいように、同薬の安価な供給をはかるために提案された同法のもとでは、南アフリカ国内の製薬会社は、特許使用の権利取得者に一定の特許料を払うだけで、より安価なエイズ治療薬を生産する免許が厚生大臣から与えられる。また、その法律には、他国の製薬会社が安価な薬を提供できる場合は、それを自由に輸入することを許可するという条項も含まれる。

抗HIV製剤

ゴア副大統領や国際的製薬会社は、開発者の利益を守るべき特許権を侵害する南アフリカのやり方が、世界貿易機関(WTO)の貿易関連知的財産権協定に違反していると主張する。しかし、その協定自体が、国家的な危機や特に緊急な場合に、コンパルソリー・ライセンスを認めている。今回の場合、エイズの状況が「国家的な危機や特に緊急な場合」にあたるかどうかである。

南アフリカの法律を認めれば、南アフリカにならおうとする国が増えるのは間違いない。そうなれば、製薬会社は治療薬の開発に注ぎ込んだ莫大な費用が回収できないし、利潤も減るわけであり、利潤を追求する企業としては、その法律に反対するのも道理だろう。国会議員や副大統領に法律撤廃にむけての圧力をかけるよう要請するのも、通常なら、無理からぬことだろう。

しかし、今春南アフリカで行われた調査の結果、生殖年齢にある成人の22パーセントがHIVに感染していると推定され、2010年までに、エイズのために国民の平均寿命が四十歳以下になる見込みであることが明らかにされたのであるから、今の南アフリカの事態が「国家的な危機や特に緊急な場合」にあたらないとは言えないだろう。アメリカは、そういった事態を承知のうえで、圧力をかけているのである。

すでに述べた老婆の嘆きを伝える1995年のジンバブエの記事の最後に、今日の南アフリカを予想してこう記してある。

医療関係者はエイズは20年前に、ザイールやウガンダのような中央アフリカから輸送経路を通って、ケニア、ルワンダ、タンザニア、マラウィ、ジンバブエに南下し始めたとみている。優れた道路が整備され、季節労働者の歴史と男性が性交渉の相手を複数持つ文化があるために、ジンバブエは特にエイズに侵されやすい。次の標的は、南アフリカで、そこでは毎日550人の人々が感染していると推計する人もいる。(註15)

アパルトヘイトは廃止されたものの、アフリカ人の安価な賃金労働者、特に短期契約の季節労働者を基盤にする基本構造を変えられないまま政権を担当せざるを得なかったANC(アフリカ民族会議)内閣は、そのような重大な事態を察知して、1997年にコンパルソリー・ライセンス法を成立させた。つまり、このコンパルソリー・ライセンス法は、エイズ危機に対する緊急措置であって、特許料をめぐって国内業者に便宜をはかることを目的としたわけではない。

南アフリカに限らず、アフリカ諸国は奴隷貿易以来、イギリスを筆頭とする西洋諸国に富を絞り取られてきた。そして、富の搾取は今も続いている。搾取する側と搾取される側の富の格差は広がるばかりである。第二次世界大戦後は、戦略を変え、開発援助なる名目で、アメリカ主導の搾取構造を維持している。国際通貨基金(IMF)、世界銀行(IBRD、通常はWORLD BANK)などの機関を通じて金を貸して利子を絞り取っているわけである。(註16)もちろん、日本も搾取側にいて、1998年度のODA予算は百億円にのぼっている。(註17)

借金が嵩んで、個人ならとっくに破産している重債務貧困国が、36ヶ国もある。(註18)このままだと元も子もなくなってしまうと、主要国首脳がドイツ・ケルンに集まって知恵を出しあい、貧困国が保有する負債全体の三分の一を削減することにした。総額七百億ドル(約八兆四千億円)である。

主要七ヶ国(G7)のODAの中で、借款の占める割合が最も大きい日本は、借金の帳消しを渋っている。円借款の予算の約半分が郵便貯金や公的年金などを財源とする財政投融資からの借入金だからという財政上の事情をその理由にあげている。しかし、「アフリカ諸国の債務帳消しに必要とされるのは、日本の場合、単純に計算して約七千億円にすぎない。日本長期信用銀行に投入された公的資金とそう違わない金額で」ある。(註19)

債務の帳消しを渋っているのは日本だけではない。ケニアなどは新たに借金が出来なくなるのを恐れて債務帳消しを渋っている。大統領モイはアメリカやイギリスや日本と組んで、新植民地政策の片棒を担いできた。巨額な援助金を我が物にして約20年にわたる長期政権を維持してきた。何度か本紙にも登場した作家のグギさんも、我が友人のムアンギさんも祖国に帰れないでいる。次の「ケニア人のエコノミスト」の厳しい批判は民衆の本音だろう。

(債務帳消しの)救済を求めないことで救われるのはだれか。ずるずる援助を受けて延命する政府と、借金棒引きがなくてすむ先進国じゃないか。結局、何の特権もない庶民が貧乏くじを引き続けるのだけは変わらない。(註20)

借金に喘ぎ、エイズに攻められる。先進国が搾取の手を緩める気配もなく、先進国の番犬を任じるアフリカ諸国の首脳は、自らの野望を諦めようとはしない。このまま放っておけば、アフリカはまさに「死にゆく大陸」である。(註21)副題の「次の20年でエイズウィルスによって三千万人のアフリカ人が死ぬ。製薬会社はその事態を更に悪くしようとするのか?」は、アフリカの危機を言い得ている。

搾取する側もされる側も、今や我欲を張っている時期ではない。搾取するにも、エイズでたくさんの人が死に、大陸そのものの存亡が取り沙汰されているのである。

今まで富を絞り取ってきた国々は、アフリカがエイズの猛威に立ち向かえるように支援することで、今こそ富を返すべき時である。エイズ患者には抗エイズ剤の安価な供給をはかること、そして、予防対策に対しての援助を惜しまないこと、それしかないだろう。幸いウガンダの例がある。八十九年に最初のエイズ撲滅運動を始めたウガンダは、感染率が人口の約10パーセントの猛威にさらされている国だが、運動の成果があって最近では感染率が目に見えて低下しているという。(註22)その成果は、本年10月14日に死亡した元タンザニアの大統領ジュリアス・ニエレレもイギリスの歴史家バズゥル・デヴィドソンも高く評価した現政権があっての故だろう。大陸存亡の危機に際して、ウガンダの例を励みに、「先進国」も「発展途上国」も、出来るところからやっていくしかない。

ニエレレ

<註>

註1 カール・マイア「エイズ流行病、南部アフリカの人々をじわじわと絞め殺す」提携紙「デイリー・ヨミウリ」(1995年7月30日)に収載の「インディペンダント」の記事。

註2 『ネイチャー』、1999年7月1日9号、1頁。

註3 註1と同じ記事。

註4 リチャード・スティーム「アメリカのワクチンがアフリカのエイズ恐怖を和らげるだろう」、「デイリー・ヨミウリ」(1998年8月29日)。「ボルチモア・サン」へ特別寄稿した記事。

註5 英文書アフリカ・ツゥデイ・シリース第二巻『アフリカ、その末裔たち 植民地時代』(門土社、1998年)の中に、この時の滞在記を紹介した。

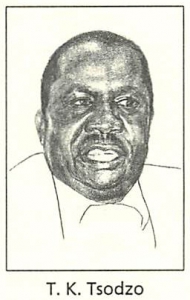

『アフリカ、その末裔たち 2』

『アフリカ、その末裔たち 2』

註6 秋山武久著『HIV感染症』(南山堂、1997年)、1~31頁。

註7 マルコム・リトルは、暗殺される直前の講演でも、奴隷貿易で果たしたカリブの島々の働きを強調している。講演は『マルコム、アフリカ系アメリカ人の歴史を語る』(パスファインダー社、1970年)に収録されている。

『マルコム、アフリカ系アメリカ人の歴史を語る』

註8 註1に同じ。

註9 註1に同じ。

註10 わだえりこ「エイズ会議終わる、しかし課題は山積されたまま」、「デイリー・ヨミウリ」(1994年8月12日)。

註11 鍛冶信太郎「新薬承認で迎える『エイズ治療元年』」、「朝日新聞」(1997年3月20日)など。

註12 ローレンス・アルトマン「世界エイズ会議、治療法も視界に見えぬまま、悲観的に閉幕する」、「インターナショナル・ヘラルド・トゥリビューン」(1998年7月6日)。

註13 「アフリカ、会議に首脳が不参加のまま、エイズの解決策を探る」、「デイリー・ヨミウリ」(1999年9月15日)。

註14 池内了「エイズが問う『政治の良心』 南ア特許法に米が反発」、「朝日新聞」(1999年8月6日)。

註15 註1に同じ。

註16 前掲書『アフリカ、その末裔たち 植民地時代』の一章(6~32頁)で新植民地戦略を詳しく紹介した。クワメ・エンクルマ著『新植民地主義 帝国主義の最終段階』(パナフ社、1965年)とバズゥル・デヴィドスン著『アフリカは生き残れるか?』(リトル・ブラウン社、1974年)は示唆的である。

註17 「日本のODA、九十八年度、十億円に達する」、「デイリー・ヨミウリ」(1998年8月28日)。

註18 「苦しい中で対応様々 重債務貧困国の実情と救済」、「朝日新聞」(1999年7月28日)。

註19 小野行雄「アフリカの債務帳消しに理解を」、「朝日新聞」(1998年12月28日)。

註20 註18に同じ。

註21 アレックス・スミス「アフリカ:放っておけば死にゆく大陸」、提携紙「デイリー・ヨミウリ」(1999年9月12日)に収載の「インディペンダント」の記事。

註22 アン・ダガン「アフリカがエイズの猛威と立ち向かえるえるように支援することは」、「デイリー・ヨミウリ」(1999年10月15日)。

<推薦図書>

山本直樹・山本美智子著『エイズの基礎知識』(岩波新書、1998年)。

国立大学保健管理施設協議会特別委員会編『エイズ 教職員のためのガイドブック’98』(国立大学保健管理施設協議会特別委員会、1998年)。

秋山武久著『HIV感染症』(南山堂、1997年)

執筆年

2000年

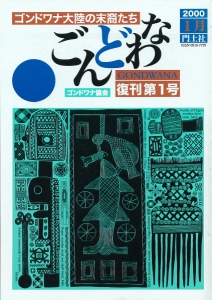

収録・公開

「ごんどわな」22号(復刊1号)2-14ペイジ

「ごんどわな」22号

「ごんどわな」22号

ダウンロード

アフリカとエイズ